- India

- International

Remembering Ebrahim Alkazi, a demanding but compassionate mentor

Theatre director and actor MK Raina on how the late theatre doyen, who passed away this week, moulded minds from across India

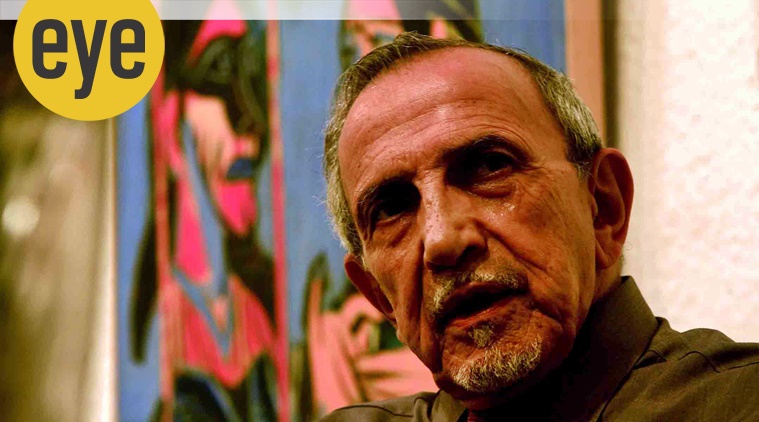

Renaissance man: Ebrahim Alkazi during an exhibition of artist KG Subrahmanyan at Triveni Kala Sangam, New Delhi. (Photo: Express archive)

Renaissance man: Ebrahim Alkazi during an exhibition of artist KG Subrahmanyan at Triveni Kala Sangam, New Delhi. (Photo: Express archive)

In 1967, I came from Kashmir as a young boy to study at the National School of Drama (NSD), whose director was the formidable Ebrahim Alkazi. It was my second or third visit to Delhi, the city that would become home once I was accepted at the drama school. NSD was very tough. You couldn’t bullshit your way through. Everything was professional and strict schedules had to be followed. Alkazi understood India very well, understood that these boys and girls were coming from all over the country and what he needed to do to mould us.

When I look back, I realise that the first lesson he gave us was on the dignity of labour. He was doing a production with our seniors called Three Sisters, by Anton Chekov, He gave me a jar of car polish and cloth and asked me to shine the entire stage. We didn’t know how to polish a stage but we had to do it. When we finished, he said, “Now you have to do backstage”. He taught us meticulously how one walks to change the sets within seconds when the blackout happens. There should be no noise, one had to move on one’s toes. He would rehearse that with us many times till we perfected it. That sense of pride I felt to backstage last till date.

The first year, we had to do a costume project. We designed a costume of a play based on Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Shoroshi. Day and night, we worked on the project, and, finally, the day came to present it. We had to go one by one to his office. The first girl who went in came out howling. I couldn’t talk to her because she was so upset. The next person, the same thing. The third girl shot out of the office. I wondered what was going on inside. My heartbeat increased as I walked in. He was very serious. He took my project, and, before he could look at it, he threw it out of the window of Rabindra Bhavan, down three floors, and told me to leave his office. I went running and picked up the project. I was mad at him. How dare he do this? He should have seen the project. I had spent two-and-a-half months on it. Luckily, the project had not been damaged. I picked it up and waited for him to come to the office the next day. The moment he came in, I opened the door and said, “I have to tell you that I am not a little boy who has come from a tiny school. I come from a university and I know what I do. You have not seen the project. Why did you throw it?”

He said, “What is it for? How do I know it is a costume project?” It dawned on me that I had covered the cover page with a newspaper. He took it and started reading news from that. I said, “Sir, give me half an hour.” I ran to Bengali Market and bought a coloured paper. I knew what was to be done. I placed the redesigned project on his desk. After two days, he had a class with us. He came in and said, “That was a good project.”

I don’t know how to define my bond with Mr Alkazi. We were friendly and respected each other but we used to fight quite often. Those fights would be about matters of theatre. I was a hot-tempered Kashmiri with a graduate degree in biochemistry. I had participated in social movements in college, unlike my classmates, who were, generally, fresh out of school.

The theatre that we see today in India gained its style, dignity and respectability from Mr Alkazi. I remember Indira Gandhi coming to see a play as prime minister at Kamani auditorium. She was seated in the fourth row because that’s the best place to watch a play from. She saw the play and left. There was no fanfare. When Zakir Husain, then president of India, came to see a play, he was late. Mr Alkazi started the play and told Zakir saheb that he could not wait. The latter said, “You did the right thing.” That was the kind of personality he was.

He used to take up to 90 classes a week and we would dream of him being absent, which never happened. In the viva, we would be asked, “How many plays have you seen? How many exhibitions have you attended? How many books have you read?” We made sure we’d go to exhibitions and meet him there.

There were times when students had differences with him and I led the complaints. Though he heard us out, he was annoyed with me. After I passed out of NSD in 1970, he would look through me as if he didn’t know me. One day, we were crossing the corridor of Triveni, and I said, “Excuse me, sir, you can’t ignore me. Don’t forgive me but don’t forget me.” He shook my hand and said, “Come tomorrow, we will have tea together.” Next morning, I went to his office. He ordered tea and we talked.

When Safdar Hashmi died, we decided to have a national mourning day on January 9, 1989. Mr Alkazi immersed himself in designing the event. It was like being his student again though we had graduated two decades ago. We would say, “Sir, hum jaante hain kya karna hain (We know what to do).” He’d reply, “Nothing doing, Raina, if anything goes wrong, your neck is on the chopper.” He became one of the founding trustees of Sahmat. We had a fundraiser and a lot of leading artists gave us their works. We had an auction at Rabindra Bhavan conducted by Mr Alkazi.

Then, there was a time when I was on the same central government panel as Mr Alkazi to give scholarships to folk artistes of India. Mr Alkazi was the chairman and I was the youngest panellist. One girl had come from an undeveloped area of Nagaland and couldn’t communicate because she did not know the language. Mr Alkazi said, “Take her and her father for lunch. Get that one NSD student from Nagaland to accompany her. Allow her to have whatever she wants to give us a demonstration.”

We made a small stage for her and she gave us a fabulous performance of puppets. We all looked at each other amazed, Mr Alkazi told me, “Raina, try to understand our responsibility. When this girl left home, she must have passed through at least 12 villages and everybody must have known that she had been called by Delhi people. Nobody there knows what Delhi people are like. When she goes back, it would be as an ambassador. She will tell exactly what we did for her here. We have to be very compassionate because artists are agents of change.” I always remember this.

The last time I met him was at his 90th birthday party in Delhi. He was not himself, not well. I was very depressed. I did not want to see him in that condition. Earlier, whenever we met, we used to chat about family and work. He would ask us to come to the studio, see his paintings. He made us aware of what a Renaissance man truly means.

MK Raina is a veteran theatre director and actor

(As told to Dipanita Nath)

Apr 29: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05