- India

- International

Dancing with the Star: The legacy of Amala Shankar, the centenarian

For a large part of her life, Amala Shankar has lived in the shadow of her illustrious partner, Uday Shankar. As she steps into her 100th year, a look back at her role in shaping a legacy.

A Life in Motion: Amala Shankar in a performance titled Grass Cutters.

A Life in Motion: Amala Shankar in a performance titled Grass Cutters.

She was an 11-year-old on her first visit abroad, across the seven seas in France. He was already an accomplished artiste, whose dance dramas — a blend of the classical and the modern — had European audiences enthralled. It was 1930, and they met in Paris. Uday Shankar, then 30 years old, asked the demure girl, dressed in a frock, to try out a few steps and twirl a stick in the air. Amala Nandy nailed every movement, as well as the expressions flitting on his face. “You’ll be a dancer,” said Uday.

Last week, at the Udayan Kalakendra in Kolkata, a celebration marked, among other things, the journey that began with that encounter in Paris. Amala Shankar née Nandy, who has lived and danced in the shadow of her partner, Uday Shankar, entered her 100th year on June 27.

In the studio where the celebrations were held, the walls hosted a montage of her life in pictures — Amala dancing; or spending time with the family; stills from Kalpana (1948), Uday’s first and only film, in which she played the female lead. Dressed in a beige salwar kameez, flip-flops on her feet, Amala was wheeled out in an office chair by her grandson Ratul. She sat still, not registering a lot of what happened around her. She sometimes raised her arms to hug some of her students and family members, but most of the time, her eyes looked into the distance.

Nevertheless, this was an occasion for her family to remind the world of her contribution to Indian dance, to the life and work of one of its uncompromising pioneers. While the trailblazing fame was Uday, Amala became synonymous with the Kalakendra, where she took on the hard work of disseminating his legacy to a new generation of dancers. She valued his unique style, the blend of so many art forms, and worked to ensure that “it wasn’t lost”.

Amala Shankar with husband Uday Shankar.

Amala Shankar with husband Uday Shankar.

Amala learned to dance during the 1930s, when women from “respectable households” were just about beginning to perform classical dance on stage. Rukmini Devi Arundale, the architect of Bharatanatyam as we know it today, held her first public performance in 1935 and set up the Kalakshetra in 1936. “If Udayji will be remembered as a pioneer who took Indian dance to a global platform, Amalaji will be remembered as the woman who stood by him, danced next to him, and took his style forward after his death,” says 88-year-old Vijay Kichlu, musician, a close associate of the Shankar family and founder of Kolkata’s famed ITC Academy.

Amala Nandy was born in 1919 in Jessore (now in Bangladesh) to a merchant family, which was interested in education and the arts. She grew up reading the works of Rabindranath Tagore, Michael Madhusudan Dutta and Nabin Chandra Sen, among others; one of her favourite stories was Tagore’s Kabuliwala. “At the time, there was no real entertainment. Ma grew up appreciating the simple things of life, like the sound of the rain,” says actor, dancer and Amala and Uday’s daughter, Mamata Shankar, 63.

In 1930, Amala’s father, Akshay Kumar Nandy, a gold trader, was invited to represent India at the International Colonial Exhibition in Paris to showcase India’s craftsmanship in gold. Of his six children, he surprisingly took 11-year-old Amala along. She was bright, a sports champion in school and “the most receptive of the six children”, says Mamata.

In Paris, they met the Shankar family — Uday and his three brothers, including the youngest, Robu (Pandit Ravi Shankar). While the brothers wowed Parisian audiences with their performances, their mother Hemangini Devi would cook and keep house.

Uday, much older, was already feted in global dance circles. After studying at the JJ School of Art in Mumbai, he had moved to London to study painting at the Royal College of Art. There, he choreographed two ballads titled Krishna and Radha and A Hindu Wedding in 1923. During one of these performances, he was spotted by Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova, who chose to partner with Uday for a year to present a slew of performances together in London and Paris.

The young Amala Shankar.

The young Amala Shankar.

Uday had never trained professionally in any dance form. He took elements from various forms — Kathakali, Bharatanatyam, Kathak, Manipuri, Odissi, and Kuchipudi — and created a style of his own. He had grown up watching folk dancers in the court of the Maharaja of Jhalawar, Rajasthan, who employed his barrister father, and their rhythm found a way into his dance. His work with Pavlova opened up his form further to the influence of ballet. According to author and art critic Shankarlal Bhattacharya, he had the eye of a painter and he saw dance differently from others. “Which is why his interpretations are so unique,” he says. Many Indian dancers, while acknowledging Uday’s contribution to dance, have also questioned it. “It’s beautiful and significant but it’s a blend of so many things. One does wonder about its purity,” says Kuchipudi dancer Kaushalya Reddy.

But the West was smitten. Irish writer James Joyce, in a letter to his daughter, wrote, “He moves on the stage, like a semi-divine being. Believe me, there are still some beautiful things left in this poor world.”

In Paris, Uday asked his mother to persuade Amala’s father to allow her to tour with him for two months. “It was unheard of, for a young girl to just go off and tour with a dance troupe. People would talk,” says Mamata, but Hemangini Devi promised to look after her and Amala’s father agreed. “When she walked around the streets, people called her tres belle (very beautiful) and that made her very happy,” says Mamata. Amala returned home after a few months. At the age of 14, she wrote a book, Shaat Sagorer Paar (Across the Seven Seas), on her experiences.

The two families kept in touch and would meet whenever the Shankars visited Kolkata. “What remained with Ma was the feeling that dance had given her. So, she longed to learn properly,” says Mamata.

Uday continued to perform in Europe. He met French pianist, Simone Barbiere, whom he called Simkey, and who became his disciple and dance partner. In 1927, while on a trip to India, he was asked by Rabindranath Tagore to set up a school. Uday wished to, but another European tour beckoned.

Amala Shankar at her birthday celebrations in Kolkata. (Express photo by Partha Paul)

Amala Shankar at her birthday celebrations in Kolkata. (Express photo by Partha Paul)

But eventually, despite the acclaim, the big concerts dried up, forcing Uday to perform in Paris bars to make ends meet. “He’d become really thin because all he did was drink olive oil and dance. The oil helped him guzzle the alcohol he needed to perform. At one time, he had to sell all of his expensive suits. He wore a newspaper under his jacket to avoid the cold,” says dancer and daughter-in-law Tanusree Shankar. Despite the hardships, he persisted. He founded Europe’s first Indian dance company, which he called Uday Shankar and his Hindu Ballet, and got the opportunity to perform at the Champs-Elysees Theatre in 1931.

Amala was still in college when Uday visited Kolkata in 1938 and invited the Nandys to attend his performance of Karthikeya in Kolkata’s Dharamtala. Uday’s entry as Karthikeya, Lord Shiva’s son, who fights a demon in an electric, Kathakali-inspired war dance, had Amala besotted. She didn’t know English well but said, “This is the man in my life.” “It was a strange thing to say, considering they weren’t even together at that time,” says Mamata.

In the years to come, in an ode to the moment she fell in love with him, Amala would watch each of Uday’s Karthikeya performances. Finally, it was on the insistence of family friend Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, who knew of Amala’s keen interest in dance, that her father agreed to send his daughter to the dance academy Uday had set up in Almora in 1938.

Uday’s dream for the academy borrowed both from Tagore’s idea of education as well as his own belief in a worldview not limited by nationalism. He wished it to be a secular cultural centre, where students would not be confined to the strictures of syllabus but would be taught to explore their artistic traditions. It drew the best of talent; Zohra Sehgal and her sister Uzra Butt, Simkey, actor Ruma Guha Thakurta and filmmaker Guru Dutt. “The academy offered a viewpoint and perspective that the world needed,” says senior dance critic Sunil Kothari, who curated a photo exhibition of Uday’s works in London in 2012.

Mamata Shankar with her mother’s old photographs. (Express photo by Partha Paul)

Mamata Shankar with her mother’s old photographs. (Express photo by Partha Paul)

Once in Almora, Amala found herself allotted a room near noisy, fume-spewing diesel generators. “My father would put her through difficult situations to see how she would cope. This was a part of her training,” says Mamata.

The academy offered an astonishing exposure to the arts. Mamata remembers her mother speaking of a Durga Puja celebration in Almora, when Kathakali maestro Shankaran Namboodri chanted the shlokas, Ustad Ali Akbar Khan played the dhaak while Amala, Zohra and Uzra had prepared the prasad.

In this environment, Amala, 20 by then, blossomed. She was tall, nimble on her feet, and was slowly finding appreciation for her expression — one of the mainstays of the Uday Shankar style. He taught with Zohra or Simkey by his side, while she was an attentive student. “Ma has always talked fondly of this period of her life. It was a different world. She was around Baba in a beautiful environment. But she was there to train and concentrated on learning. I have been able to understand Simkey and Zohraji’s style because Ma showed me. She watched, very carefully, the way they moved,” says Mamata. Amala also learned Manipuri classical dance from Amoubi Singh, Kathakali from Nambudiri, and Bharatanatyam under Kandappa Pillai.

But Kichlu wonders how Amala must have felt, watching Uday being attracted to the many women at the centre. “He (Uday) was in love with Simkey, who was a pianist but left it to learn dance,” Ravi Shankar had said in an interview. Imagine her surprise, then, when Uday asked her to marry him in 1939. “She worshipped him, so when he asked ‘Do you know the name of the woman I’m marrying?’, she’d said no. She was in tears when he uttered her name,” says Mamata. Amala kept the engagement a secret from others at the institute. “Everything happened in her presence and she still decided to marry him. My only conclusion is that she really worshipped him,” says Kichlu.

A little before Uday and Amala tied the knot in 1942, the centre had to be shut down due to lack of funds. The two had a son the same year — Ananda, who went on to become a reputed composer and dancer. Mamata was born 13 years later.

The disappointment of having to close the academy gnawed at Uday. He responded with Kalpana, a film he shot at Gemini Studios in Chennai over five years, on a budget of Rs 22 lakh. It was the story of a man who wanted to set up an arts centre in the Himalayas, a place which would finally convince the world of the importance of arts and an education system that planted the seeds of creativity. The film was biographical, of course, but a critique of the society he lived in.

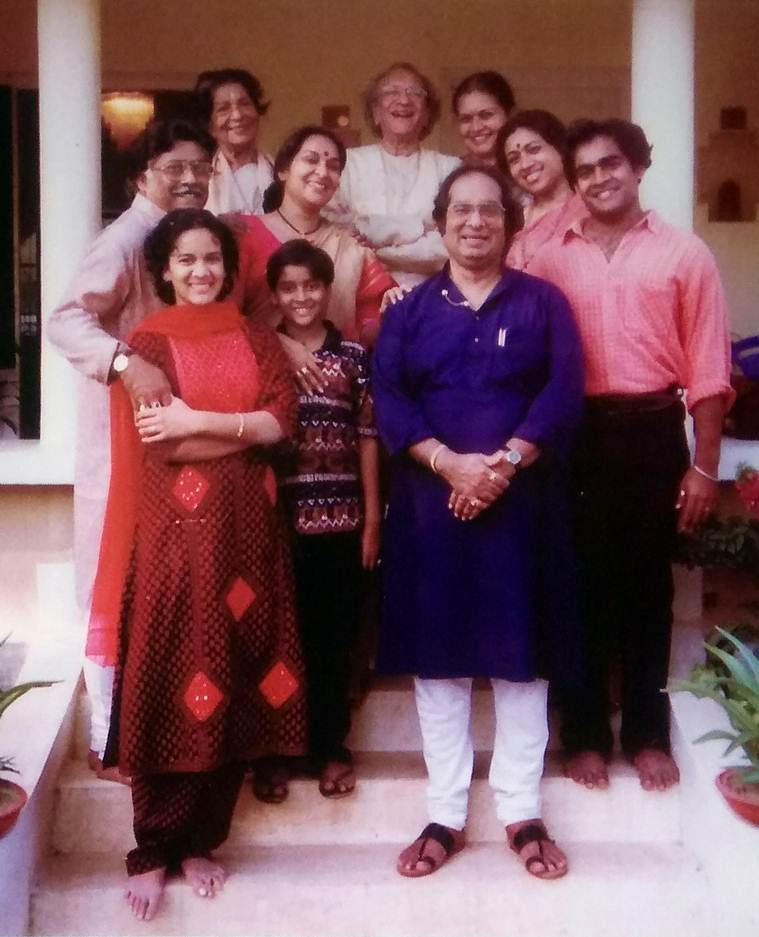

Amala Shankar with Ravi Shankar and her family.

Amala Shankar with Ravi Shankar and her family.

At first, he named his dream project, ‘Imagination’. But Amala wasn’t convinced about an English name for a film in Hindi. “She changed it to Kalpana,” says Mamata. “Baba agreed. He wasn’t only her teacher and husband. He had immense respect for her as an artiste and was receptive to her ideas.”

Kalpana tanked as soon as it was released in 1948, a year when competing films included Dev Anand and Kamini Kaushal’s Ziddi and Mela, which featured Dilip Kumar and Nargis. “India’s failure to recognise Kalpana was extremely sad. Uday Shankar’s only film was like a painting, a criticism of Indian life,” says Shankarlal Bhattacharya about the film that Satyajit Ray is rumoured to have watched 11 times.

Despite its box-office destiny, Kalpana’s dance sequences were talked about for years to come. Be it the Bharatanatyam-inspired Tandav nritya, with Uday and Amala as Shiva and Parvati, or Amala’s spunky Bhil folk dance, and the climax, where she heads a group of women on stage, who have rejected saris to stomp out in kurtas and churidars, dupattas be damned.

The lyrics of the film were penned by poet Sumitranandan Pant. “If Udayji conceived these pieces, she executed them beautifully. In many ways, she was the kalpana he had in mind,” says Kichlu. Besides being brilliant in the language she learned from Uday, she was equally at home with the classical and the avant garde. Most dances in Kalpana are a blend of various Indian classical dance forms, folk and western ballet. “You will find her comfortable in every kind of piece she delivered,” says Mamata.

The Shiva-Parvati piece, especially, has found a mention in almost every book written on Indian dance ever since. Uday depicts the cosmic cycle of creation and destruction with his vigorous, brisk movements, and the famed hasta mudra. Amala, who plays Shiva’s feminine counterpart, responds with lasya, the dance of aesthetic delight that symbolises eroticism through delicate, subtle and graceful movements. Together, the two create a riveting performance. “But we always tend to notice Shiva more than Parvati. He is handsome, virile, masculine and a serious performer. She is beautiful, too, but in a complementing role. That’s why one notices Udayji more than Amalaji in this performance. She, however, is the backbone here. Shiva is incomplete without Shakti. The latter is the shadow here but equally significant,” says Reddy.

Amala Shankar at Cannes 2012. (Express photo by Partha Paul)

Amala Shankar at Cannes 2012. (Express photo by Partha Paul)

Likewise, Amala remained the cornerstone of the Shankar family. While Uday was the creative genius, she was the administrator. She planned the costumes, rehearsed his choreographies with the dancers and took care of the tiniest aspects on tour. When she wasn’t touring, she taught extensively. “A strict mother but a gentle teacher, she was as particular about how one had to wear a bindi, as about how the sari needed to be tied and how the capsicum needed to chopped. She has always wanted things a certain way and that’s what was drilled into Ananda and her students and me. You couldn’t take a short cut,” says Mamata.

In 1965, Uday set up the centre in Kolkata, with Amala as the director. Over the next 50 years, she taught a number of students, many of whom became noted dancers. One of them was Tanusree Shankar, who later married her son and composer Ananda Shankar. “She’s always been a disciplinarian, but a very gentle teacher. She’d repeat a step if I didn’t understand something. I married Ananda when I was 17. I was only a child and she looked after me like her daughter, teaching me everything I know,” says Tanusree.

To Mamata and many of her students, she was a perfectionist. Among many of Amala’s students is Anuradha Lohia, now the vice-chancellor of Presidency College. “It’s not just dance, she taught me conduct, patience, and strength. Only a great teacher can inculcate value systems alongside an art form and she did exactly that,” she said.

As Amala came into her own as a teacher, Uday, now in his 70s, was a shadow of his former self. He missed the adulation of yore, the intoxication of applause and youth. He even asked Amala to shut down the centre. When she refused, he moved out. There were also whispers of his dalliances and mental illness. “Dada was a wonderful man, but women were a weakness and that led to issues ,” says Kichlu.

The two separated a few years before Uday’s death in 1977. He moved to a one-room apartment and was estranged from the family in the last few years. Mamata says her parents kept in touch and would speak over the phone. Two days before he died, Uday called Amala near him, kissed her forehead and said, ‘Thank you Amala, thank you for everything”. “There may have been a rift towards the end and many people may have said many things, but these two loved each other and that’s the truth,” says Mamata.

Uday had bequeathed his costumes, masks and the prints of Kalpana to one of the centre’s students, Anupama Das, who looked after Uday in his last years. Two decades after he died, she sold the rights of Kalpana to the wife of one of the directors at Film Services, a Kolkata-based production house, for Rs 5,000. Mahendra Kumar, an Uday Shankar associate appointed as restorer and marketer of the film, filed a PIL against the decision along with the Shankar family.

Some years later, Ravi Shankar mentioned Kalpana to filmmaker Martin Scorcese in a casual conversation. Scorcese decided to restore the film but since it was stuck in legal battles, a duplicate print was sourced by filmmaker Shivendra Singh Dungarpur from National Film Archives of India, Pune (it had been preserved by NFAI founder PK Nair). It was restored and screened at Cannes in 2012. Amala walked the red carpet to watch the screening of a film that had brought her fame in 1948. “At 93, I’m the youngest film star you have at Cannes this year,” she said with a laugh.

Amala is described by those who know her as a private person, the calm centre of a storm. She continued to teach even after son Ananda’s death from heart failure. “She is made of something else. His death crushed us but she was our strength,” says Mamata.

In her 100th year, Mamata and Tanusree want Amala to be remembered as her own person, a dancer with her own unique identity. “She understood Uday Shankar’s language so beautifully — a language that was highly original and yet quite modern. She lived it and taught it,” says Kichlu.

Buzzing Now

May 04: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05