- India

- International

Night Shelters: Hidden city of the homeless

Over the last nine years, govt has set up 205 additional night shelters, equipped some with geysers and CCTV cameras.

The night shelter at Yamuna Pushta on the Yamuna floodplains, which gives shelter to 300-odd people, is run out of a porta cabin. (Express Photo: Gajendra Yadav)

The night shelter at Yamuna Pushta on the Yamuna floodplains, which gives shelter to 300-odd people, is run out of a porta cabin. (Express Photo: Gajendra Yadav)

AT 40, Uttam Thapa’s memory betrays him. He has forgotten his father’s name, the name of his village and his address. About all these, he has only a monosyllabic answer — Nepal. Homeless for nearly three decades, it is all that has remained with him of his life before Delhi.

Among the nearly 300-odd homeless men who turn to the night shelter at Yamuna Pushta for warmth and solace, Thapa works as a daily wage labourer in the capital, where he had somehow managed to make his way to as a teenager. “We get food from the nearby temples, usually khichdi. The night shelter provides us with blankets, and that is enough. Whatever money I make from the odd jobs I do is enough to sustain myself. When work is lean in Delhi, I move elsewhere,” he said.

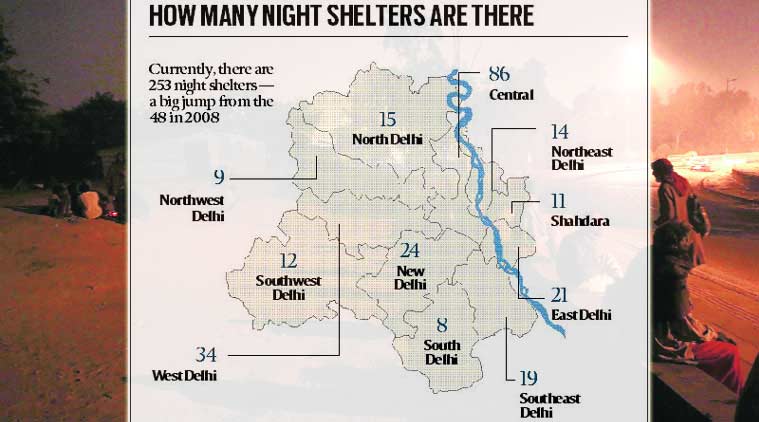

One of Delhi’s floating, forgotten homeless, Thapa’s story is not uncommon. In a city that encroaches its margins as it expands, these marginalised men, women and children turn to the night shelters to prepare for yet another day. Currently, there are 253 night shelters in the city — a big jump from the 46 in 2008. Of these, there are 83 permanent structures, 113 porta cabins and 55 temporary shelters — usually tents made out of thick fabric, which can accommodate around 20,000 people.

In 2001, the Census pegged Delhi’s homeless at 21,895 while an independent study by Ashray Adhika Abhiyan in 2000 claimed the number stands at 52,765. The 2011 Census found that there are 46,724 homeless people in the city. The same year, the Supreme Court Commissioner’s Office (SCCO), Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB) and other NGOs conducted an enumeration of the homeless population and found the figure to be 2,46,800.

DUSIB officials say that the homeless in the capital are migrants who come here, particularly from Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Odisha, for work. “When there are thriving opportunities, they live on the streets. When there is less work, they move to other states,” said Bipin Rai, a member of DUSIB.

In 2015, when the AAP came to power, it tried to revamp the services that the state provides for the homeless in winters. To ensure no one dies due to exposure to the cold, Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal issued orders for setting up of new night shelters, besides adding 33,000 blankets, 14,000 durries and 11,500 jute mats to the existing stock. It also attempted to arrange for new night shelters and tents to accommodate at least 19,000 people.

But even though the number of night shelters has increased over the last couple of years, ones with permanent structures continue to be few. The problem, DUSIB officials explained, is the unavailability of land, especially in central Delhi. “If we ask for land, we are offered spaces in outer Delhi or west Delhi, where there are hardly any homeless,” the official said.

The conflict between the economics of land and the reality of the homeless also reflects the “manner in which the homeless are viewed”, an official explained. Night shelters, he said, were constructed at places where those who needed them tended to congregate. “Although the governments have viewed the problem as an economic one — of people not having money — it is not purely that. It is more systemic. Whether a gated colony or a shop, no one wants a homeless person outside. But they need to be in areas where there is work. So, when night falls, they are pushed further away from the centre of the city,” he said.

The largest concentration of night shelters is along the Yamuna, where no permanent structure can be made, or Delhi 6, where there is scant space for new constructions.

The Delhi government is now considering to convert condemned DTC buses into mobile night shelters. “The idea is to convert these buses into shelters that can be parked in central Delhi at night and driven out in the morning. We will be able to create space for at least 50 people by removing the seats,” said Rai, adding that the matter is pending with the Cabinet and is expected to be approved soon.

The night shelter at Yamuna Pushta on the floodplains operates out of a porta cabin. As the fog rolls in from the river and causes the chill to set in at night, occupants of the shelter get protection with the help of two jute mats, 250 durries, 350 blankets and a single tap that dispenses hot water. In summers, 16 ceiling fans and four desert coolers make a similar attempt to counter the heat radiating from the metal roof. “It is not much but this structure is new. We get food from the nearby temples or Nigam Bodh Ghat. Besides, we can always get some alcohol to keep us warm,” said 30-year-old Rajesh Kumar, who hails from Bhopal.

As part of its winter action plan, the Delhi government on November 15 planned to equip its night shelters running out of permanent structures with TV sets and geysers. “Of the permanent ones, 20 are reserved for women and 23 for families. All 43 are fitted with CCTV cameras,” said DUSIB CEO Shurbir Singh.

At a shelter in Old Delhi. (Express Photo: Gajendra Yadav)

At a shelter in Old Delhi. (Express Photo: Gajendra Yadav)

The government also plans to set up, on pilot basis, a solar geyser at a porta cabin-based shelter at Geeta Ghat to test its efficacy. Besides, the government is also procuring more mattresses, pillows, geysers and 50 bunk beds.

For now, there’s no hot water at the Yamuna Pushta shelter, and problems are plenty.

“Since we can’t build permanent structures along the river, there is no wall to fix a geyser. Also, water at the portable toilets comes from below. Hence, there is the additional question of how to pump the water up,” said Rai.

An official said the bunk beds have led to unexpected issues. “We found that no one wants to sleep on the top bunk. A number of those who come to the night shelters are inebriated. They are afraid they would fall off. No one wants to sleep in the lower bunks because they worry the person sleeping on the top might urinate on them,” said a DUSIB official.

However, he said, bunk beds will be reintroduced in shelters for children and families. “Children get excited with the concept. They enjoy sleeping in the top bunk,” the official said.

At a night shelter in Urdu Bazaar in Old Delhi, there are separate spaces earmarked for women, children and families. By 1 am, the metal gates outside are locked.

Caretaker Deepak Barnwal explained the reason: “Police have asked us to lock the gates after 11pm for the safety of women and children staying here. Besides, there were a number of robberies here. Moreover, since construction work is ongoing, a lot of expensive equipment are lying around.”

At the shelter, Arun Kumar, who claims to be 12, says, “I ran away from home three-four years ago. It was winter but I managed to get by. Now I have made friends. We beg at different traffic signals but come back here at night. I get food from temples and mosques, sometimes people donate clothes. This is my second night at this shelter. Before this, I was at Paharganj. But I moved since police would make us strip to see if we had any valuables on us.”

The NGO that runs the shelter offers classes for children but Kumar is not interested.

Express file photo

Express file photo

Caretaker Barnwal, himself a migrant from Jharkhand, understands the lure of a big city like Delhi and empathises with those who find it hard to cope. He came to Delhi six years ago and started selling tea near a shelter in Asaf Ali Road. Soon, he was hired by the NGO that runs the shelter. “I was lucky, others are not. If things had gone differently, I could have been one of them. The line between those who are homeless and those who are poor is very thin.”

At the night shelter on the other side of Meena Bazaar, some new faces arrive at 1 am. After questioning them, the shelter opens its doors. “We can’t be too careful. There are over 50 women. Although the government has set up CCTV cameras, this is an unsafe neighborhood,” said Mohammad Yakub, the caretaker.

Looking at the new entrants, a 45-year-old woman says little but makes it evident that she is suspicious. She later explained: “It is hard for women to be out on the streets. Men, including police, trouble us. So of course, I am afraid when I see the gates opening at midnight.”

In 2015, the Delhi government had launched a mobile app to help in the ‘rescue’ of homeless people during winters. Users can download the app and inform DUSIB of the location of a homeless person, so that the nearest rescue team can come to the location. “The users have access to a list of shelters and can inform the nearest shelter about the homeless person’s location. After a rescue operation is completed, the user is sent an update,” said an official at the DUSIB control centre.

Since November 15 this year, the 20 rescue teams operating in Delhi have received 112 complaints and shifted 3,832 homeless people to night shelters.

(Express photo by Oinam Anand)

(Express photo by Oinam Anand)

However, 54 people refused to move.

“It is not uncommon to find people who refuse to move. Once, when we tried to take some people to the shelter, they got angry, abused our teams. We had to record videos to show the government that we were not making the incident up,” said Yakub.

An official explained, “Many homeless people keep wares that they sleep next to. They are afraid of the night shelters because they are worried that someone might steal their wares. Others are afraid that we will send them to an anath ashram. But the most common reason for not seeking refuge at a night shelter is because they prefer being out in the open.”

Mohammad Arshad (43), who begs on the road outside gate number 3 of Jama Masjid, said, “Why would I want to sleep at a shelter? The streets are my home.”

Such contradictions are common in the capital. Take for instance, the Delhi government’s announcement of mobile health teams that were envisioned to check each shelter twice a week. The only problem: these teams aren’t very mobile.

“We don’t have vehicles yet. So we can only go to the shelters in our own vehicles. But we have heard that the file has been approved and the vehicles will be available to us soon,” said Dr Sushil Michael from the Department of Health Services. He says the most frequent ailments plaguing the occupants of the shelters range from cold, cough to minor bruises and scrapes. For emergencies, the government provides ambulances to rush the patients to the nearest hospital.

But caretakers at night shelters and those who reside there speak of an unavoidable “bias”.

Prem Chand Rajput (42), a regular at the Meena Bazar night shelter, said, “Recently, a friend of mine was having trouble breathing. The ambulance staff refused to travel alone with him. They said yeh kanjar ke saath hum nahi jaayenge, so I offered to go. At the hospital, doctors ignored him until there was no other patient left.”

Doctors also speak of other life-threatening ailments that the homeless suffer from. “Last year, I came across three-four cases of tuberculosis. We provided them with medicines. But since it is a floating population, it is hard to monitor them,” said Michael. But often, this isn’t enough.

Since November this year, the Zonal Integrated Police Network (an MHA initiative) has found 463 unidentified bodies on Delhi’s streets. The government admits it was impossible to identify how many of them were homeless.

A Delhi government official said, “Ads are put out. If no one claims a body, it is cremated within three days. Mostly, the homeless have no one to look out for them. When they die, that is it. They disappear, almost as if they weren’t there to begin with.”

Underneath a flyover in Nizamuddin, which offers some shelter to those who have failed to find space at the shelters, fires are lit furtively. With the NGT’s orders against open fires, police crackdown has been swift. “Every year, there is a new law. We don’t even know what is for real. This year, they told us that we can’t light fires. But what else can we do to keep ourselves warm?” asks Akhilesh Singh, who hails from Mewat.

As cars rush homewards, he huddles closer to the flames, embracing the few inches he calls home for the night.

Apr 25: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05