You still meet people, in their 70s or 80s now, who recall the night they saw Jimi Hendrix as a defining moment in their lives, one of the things that made their lives worthwhile. That’s how I feel about Roger Federer. Last year, having watched him play just once before – sweeping aside a now forgotten opponent in an early round of Wimbledon in 2012 – I was courtside for every one of Roger’s matches on his way to winning the titles at Indian Wells and Wimbledon. It was a great achievement – my being there to see him, I mean.

At Indian Wells, a friend and I attended the press conference after Roger had walloped Jack Sock in the semi-final. When he entered the room and we saw him up close for the first time, both of us – I was at the tail end of my 50s, my friend was 52 – gasped like adolescent girls catching a glimpse of Justin Bieber, or whoever the new Justin Bieber might be. Compared to some of the other hunks on the tour, and especially next to his long-time rival Rafael Nadal, Federer’s arms seem almost feeble. Up close, though, he looks like a Greek god – it’s just that his signature ease of movement on court distracts us from the physical strength that has powered that fluency and delicacy for all these years. Like a dancer, part of his talent lies in concealing the effort needed to make grace appear effortless.

It was also at Indian Wells, seeing the huge crowds gather around the practice court an hour before Federer was due to appear for his session, that I started seriously to wonder what it must be like to be Roger. Not just to be widely considered the greatest tennis player of all time, but to be so loved, so adored. Like many people, I’d loved Roger for years and then, about five years ago, realised I loved him even more than I had before. This had to with his vulnerability. Back when he was winning everything and beating everyone – except Nadal at Roland Garros – we took his greatness for granted. Then the cracks began to appear. There was the difficulty of dealing with Nadal’s high, topspin balls to his backhand, at first on clay, eventually on all surfaces; there was the sheer relentlessness of Novak Djokovic; there were the occasional niggling injuries.

There was also – and I mention this after all the tennis-related issues, even though it predates them – his dismaying decision to take to the court at Wimbledon in 2006 wearing a cream blazer, as though arriving not for tennis but a party on Gatsby’s lawns. (The monogrammed cardigan of 2008 at least had the virtue of looking sporty – in a croquet at Brideshead sort of way.) It was after all this, but long before the knee problem and surgery that led to his 2016/17 sabbatical and eventual resurgence, that my – our – adoration reached its properly mature phase. We were glad that he kept playing, giving us a chance to see him, even if only on TV, even though a pattern seemed set whereby he sailed through the early rounds before coming up against either the swirling menace of Nadal’s left hand or the Balkan wall of Djokovic’s implacable defence. One wonders, also, if Nietzsche’s observation might have played a part in this post-omnipotent phase of his life, especially if we alter “victory” to “victories”: “What is best about a great victory is that it rids the victor of fear of defeat. ‘Why not also lose for once?’ he says to himself; ‘now that I am rich enough for that.’”

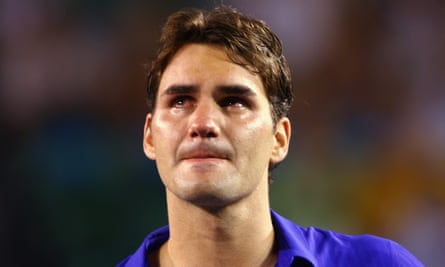

As those losses mounted, something else became manifest. Roger had always been generous in victory – that came easily, of course – but defeat often left him floundering. Losing to Nadal in Australia in 2009 reduced him to tears (“God, it’s killing me”), testing his graciousness to the limit. Thereafter, losing became something Roger accepted with a grace commensurate with his game. It needs emphasising that he is not alone in such displays of sportsmanship. Rafa was even more generous than Roger in Melbourne, muting his celebrations because of his affection for the king he had just deposed. So while Roger may not be uniquely magnanimous in defeat, he is a defining part of a golden age of tennis manners. We have become sufficiently accustomed to this that we are now struck by a lack of good sportsmanship, as happened when Marin Cilic, a player of monstrous power and still more monstrous tedium, failed even to mention Roger in his speech after being whupped by him in last year’s Wimbledon final.

Not that we really cared. All that mattered was that Roger had won his second major of the year, bringing his tally to 19, to be followed, this year, by his 20th and a return to the No 1 spot where he is currently perched, precariously, ahead of Nadal. He has again demonstrated that the most efficient way to play tennis is also the most beautiful, that aesthetics and winning can go hand in hand. Last year’s Australian Open was the victory he had craved after all those years of falling short. Everything after that was going to be gravy. And so he has become still more relaxed, more gracious, funnier, more charming.

It would be unfair to say that Kyle Edmund, in his post-match interviews, seems rather charmless compared with Roger. Federer has been wooing audiences, in multiple languages, for more than a decade and is as comfortable appearing on TV as he is watching it on his couch. (John Isner, after winning his first Masters 1,000 title, at Miami this year, joked that he now knew what Roger felt like every other week.) In Melbourne in January, Roger’s post-match interviews with Jim Courier got longer and more enjoyable with every round. He’s funny, he’s cool, the one thing he’s not is… With the possible exception of “respect”, no word in the English language is presently misused more than “humble”. When a male writer or actor says he has been humbled by the receipt of some prize or other, it translates roughly as: “I’ve got the biggest hard-on you’ve ever seen.” People routinely described Usain Bolt as humble, even though he spent most of his time bragging about being a legend. They may not be pompous or grand, but there’s nothing humble about either Bolt or Federer. What they both are is relaxed and nice.

I’ve never met him – never met the man I instinctively call Roger – but everyone who has says the same thing: how incredibly nice he is. At Wimbledon last year, one of the journalists sitting near me told a story about sharing a car with Ilie Nastase and what a complete pig he was. Then another told a story about sharing a car with Roger. What was he like? We knew what the answer was going to be: he was so nice.

Several years ago, George Saunders published an essay recalling his time at Syracuse University, where the writer Tobias Wolff served as a mentor and teacher. One day, after Wolff had published a story in the Atlantic, Saunders spotted him in the English department: “There he is: both writer and citizen. I don’t know why this makes such an impression on me – maybe because I somehow have the idea that a writer walks around in a trance, being rude, moved to misbehaviour by the power of his own words. But here is the author of this great story, walking around, being nice.” Later, after Toby and his family leave Syracuse for California, Saunders and his wife move in to the house where the Wolffs used to live. As George sits out on the porch, unseen in the dark, a couple pass by. “‘Oh, Toby,’” the woman says. ‘Such a wonderful man.’” Saunders makes a note to himself: “Live in such a way that, when neighbours walk by your house months after you’re gone, they can’t help but blurt out something affectionate.” Niceness, in other words, is something to be aspired to.

True to his resolution, the now famous Saunders is also famously nice. His students will, in turn, be beneficiaries of this legacy and genealogy. Roger, it seems, is not much of a reader, but early on he adopted as his motto the line: “It’s nice to be important, but it’s more important to be nice.” After Federer beat Andy Roddick in the Wimbledon final of 2005, Roddick told him: “I’d really like to hate you but you’re just too nice.”

Now, this celebration of niceness is, I hasten to add, not a plea for blandness. There’s something intoxicating about the way that a victorious fist-pump from Fabio Fognini can transform the red clay of the Italian Open into the gore-streaked red of the Colosseum in the reign of Commodus. Speaking of gladiators, the world would be a far duller place without the kind of post-fight interview in which Mike Tyson, deranged by his own badness, said he wanted not only to rip Lennox Lewis’s heart out but to “eat his children”. Boxing, this reminds us, is a world apart from other sports. For Joyce Carol Oates, in fact, it’s not a sport at all, let alone a game: one plays football or tennis, she wrote, “one doesn’t play boxing”. Tyson’s mentor and trainer, Cus D’Amato, made sure that there was no relief, in any situation, from the dread inspired by his fearsome charge.

While an aura of invincibility is a valuable asset for a tennis player – a constantly unsettling reminder that he can come back from two sets and a break down – this is entirely compatible with WH Auden’s claim that it’s better to be “liked than dreaded”. So when Stephen Tignor, in his book High Strung, writes that encounters between Jimmy Connors and John McEnroe “were knife fights”, one must politely demur: “No, they were tennis matches. Even when things turn ugly, the amount of physical contact between tennis players is minimal, as when Lukas Rosol shoulder-barged Andy Murray during a changeover in Munich in 2015. “No one likes you on the tour,” came Murray’s hardly Tysonian response once they were back at opposite ends of the playground. “Everyone hates you.”

Relatively speaking, then, the man everyone loves really blew his lid in the course of losing to Juan Martín del Potro at Indian Wells in March when, in the words of an academic colleague of mine: “Roger started acting like a little bitch.” That’s true, but, given the intensity of competition, the surprising thing is that there have not been more on-court eruptions of the kind that punctuated Federer’s teenage years and which came almost to shape the tennis personality in the heyday of McEnroe and Connors.

It could be said that it’s easy to keep your cool when you are the best in the world, but it’s equally true that the vast world beyond the tennis court – or film set, recording studio or concert hall – offers the eminent unfettered opportunities to reveal their true colours. Hence the plea of celebrities caught behaving horribly: “That wasn’t me” – ie, it may have been me, but it wasn’t the real me. Susan Sontag and VS Naipaul, to give them credit, gave free rein to their manifest awfulness. Both believed that the seriousness of their literary vocation demanded immunity from any of the normal claims of decent behaviour routinely exemplified by Wolff, universally ranked more highly than Sontag as a writer of fiction, and Federer.

Alongside his tennis skills, the latter’s marketable niceness has turned into a nice little earner. Just as Roger was contractually obliged to be clean-shaven when sponsored by Gillette, so his brand depends on his being seen to be nice. In the privacy of his home or hotel, does he hurl his eggs across the room if they are not poached quite to his liking? Does he plunge into a day-long sulk if his wife, Mirka, even mentions Rafa’s biceps or tucks into his stash of Lindt chocolates? We don’t know, but it seems that being nice – which must have been part of his basic disposition – has also become a habit by virtue of behaving nice. (I put it like that because, in tennis-speak, there are no adverbs; one does not serve well or powerfully, only “big” or “great”.) Putting added spin on John Updike’s line about celebrity – “a mask that eats into the face” – the image has imprinted itself on the psyche.

This is a love letter, obviously, but it could be from almost anyone. Roger has become one of the most beloved people on the planet. He’s not an intellectual but he is the tennis player adored by artists and intellectuals. He’s not especially good-looking – that nose of his would probably not look much worse if he’d been in the ring with Tyson – but the beauty of his game both envelops him in gorgeousness and tempts us into assuming that he must have a great appreciation of beauty in everything. This is not the case. He’s just a tennis player, after all.

What certainly seems true is that the more we love him, the nicer he becomes. It’s like the concept of darshan in Hinduism, whereby we are blessed by being able to see the gods who, as a result of our seeing them, become more god-like.

On a personal level, I feel sure we’d hit it off if we could hang out together. I’ve got a great sense of humour, too, Roger. I was only joking about that nose. It’s a great nose, it suits you: as Jack Nicholson says in Chinatown, I’m sure you like breathing through it. More to the point, if you’re as nice as everyone says, surely you can get me into your box for this year’s Wimbledon final. Actually, just in case you don’t make it that far, could we say the quarters?

Geoff Dyer’s latest book, The Street Philosophy of Garry Winogrand, is published by the University of Texas Press. A new book, “Broadsword Calling Danny Boy”: On Where Eagles Dare, will be published by Penguin in October

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion