Nnearly 150 years ago, the German chemist Adolf von Baeyer synthesised a powder that would become the preferred weapon of anti-corruption crusaders in India. The chemical was phenolphthalein—an odourless, tasteless and insoluble white talc that, when dissolved in treated water, turns glowing pink.

Yes, you got that right. Phenolphthalein is the powder smeared on currency notes to help investigators nab bribe-takers. The magic compound has trapped thousands of corrupt Indian officials over the past few decades, mainly because it provides incontrovertible proof that an individual has demanded and accepted illegal gratification. Countless Indian movies have dramatic scenes of investigators forcing chagrined officials to dip their fingers in bowls of water that instantaneously turn pink. What the movies do not often show is that the water is preserved and presented in court as evidence, long after the culprit gets caught.

Has phenolphthalein helped reduce corruption in India?

Yes, indeed. A measure of its success is the fact that the National Institute of Criminology and Forensic Science in Delhi has put up a detailed write-up to educate people on how the chemical helps them trap corrupt officials. The 13-page document reveals procedural aspects ranging from spotting suspects to making pre-trap arrangements.

Obviously, the smart among the corrupt have evolved new ways to collect bribes. Some employ touts to hang around government offices to lure people and take their money. The idea, apparently, is to ensure deniability for bureaucrats.

Also read

- Indices: Where India stands in global rankings

- India's demography: All's not well

- Climate change performance index: India rank 11

- Poverty index: India rank 49

- Health care: India needs more doctors

- India needs to spend more to educate its people

- Human rights a messy issue in India

- Liveability index: No Indian city in top 100

Some, however, never learn. In January this year, the station house officer of Sector 20 police station in Noida and three journalists were arrested for taking Rs8 lakh as bribe. The SHO had demanded the money for removing a call-centre owner’s name from an FIR filed against him. The journalists arranged the deal apparently. The group of four was so careless, though, that the investigators found the phenolphthalein smeared across an unlicensed pistol, six cellphones and a Mercedes-Benz car.

The determined crackdown on corruption—in the past few years, especially—has benefited a large section of Indians. The advent of e-governance technologies has also ensured that people can now access government services without going through middlemen and bribe-taking bureaucrats.

But there is fear about corruption getting institutionalised. The electoral bonds scheme, for instance, has made political funding less transparent and more controversial. So far, around 90 per cent of funds from such bonds have gone to the ruling BJP.

“The introduction of the scheme is part of what appears to be a growing trend away from transparency and accountability, two values that were already sparse in relation to Indian political parties,” said a 2018 report by the Delhi-based think tank Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy.

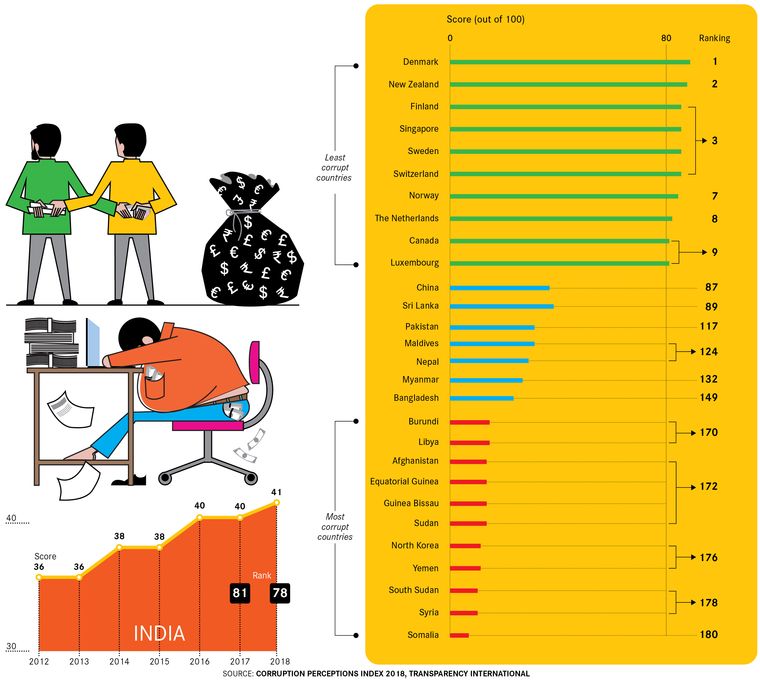

Apparently, phenolphthalein alone cannot solve the problem. India’s low ranking in the corruption index reflects that ugly truth.