Rasam during Covid-19 lockdown: an Indian comfort food staple, delicious and medicinal

- Known for centuries as a healing food, rasam has been cooked across South India during the pandemic to boost immunity

- Seen as part of the Indian Ayurvedic tradition, it has evolved to include all sorts of ingredients, including fruit

Growing up in Chennai, South India, one of my earliest memories is of my mother feeding me rasam, a peppery soup with a flavour of asafoetida and curry leaves, and rice, with a dollop of ghee (clarified butter).

A piquant mix of flavours with tamarind extract, tomatoes, spices and sometimes lentils, a bowl of rasam is seen as comfort food across the South Indian states of Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh (where it is called chaaru), Karnataka (where it is referred to as saaru) and Kerala.

Given its long history of being a healing food, it’s little wonder rasam has become a staple food prepared at home during Covid-19 lockdowns throughout India to boost immunity.

Rasam is derived from the Sanskrit word rasa – which means essence or extract. Rasam is traditionally prepared with tamarind water and black pepper.

The late food historian KT Achaya, who chronicled almost every ingredient commonly used in Indian kitchens, refers to an early description of rasam by Niccolao Manucci. The Venetian doctor, traveller and writer lived in India around 1650AD and wrote about Indians “sipping a concoction, which is some water boiled with pepper”.

Food is their medicine: South Indian vegetarian dishes explained

Muthukumar Gurusamy, executive chef of the Novotel Chennai OMR hotel says rasam can be both an appetiser and a digestive.

“It is an integral part of lunch in many South Indian homes, comprising digestive-boosting ingredients like cumin, black pepper, coriander, asafoetida, and appetising ingredients like tamarind, tomato and garlic. Rasam has got your back in both sickness and health,” Gurusamy says.

Every household has its own repertoire of rasam – from a simple tomato and lentil rasam to even a pineapple, neem flower, lemon, and watermelon rasam.

My grandmother had a repertoire of more than 30 – from a pepper and ginger rasam to a garlic rasam. She usually made it in her trademark eeya chombu, a tin and lead vessel that added to its taste, with almost religious reverence to ingredients, tempering it with mustard, cumin and fresh coriander leaves. She also made her own version of a rasam powder with pepper, cumin, red chillies, roasted and ground at home.

Coronavirus: Indians seek ancient home remedies to boost immunity

Some standard ingredients go into the base of a rasam. Krish Ashok, a techie, musician and author of an upcoming book on Indian food science, posted a YouTube video in which he provides a template and method for making every variety of this dish. He categorises its ingredients into stock, acid, flavouring and tempering.

“A stock could be water, lentil, or chicken or mutton stock. The acid is usually tamarind and the tempering is usually in clarified butter using spices like mustard, cumin, red chillies. Though most people think rasam is vegetarian, that’s not true. There are meat versions of rasam and most people in the coastal areas would use any stock without wasting it,” he says.

He says you can even make a Thai rasam with galangal, lemongrass and basil.

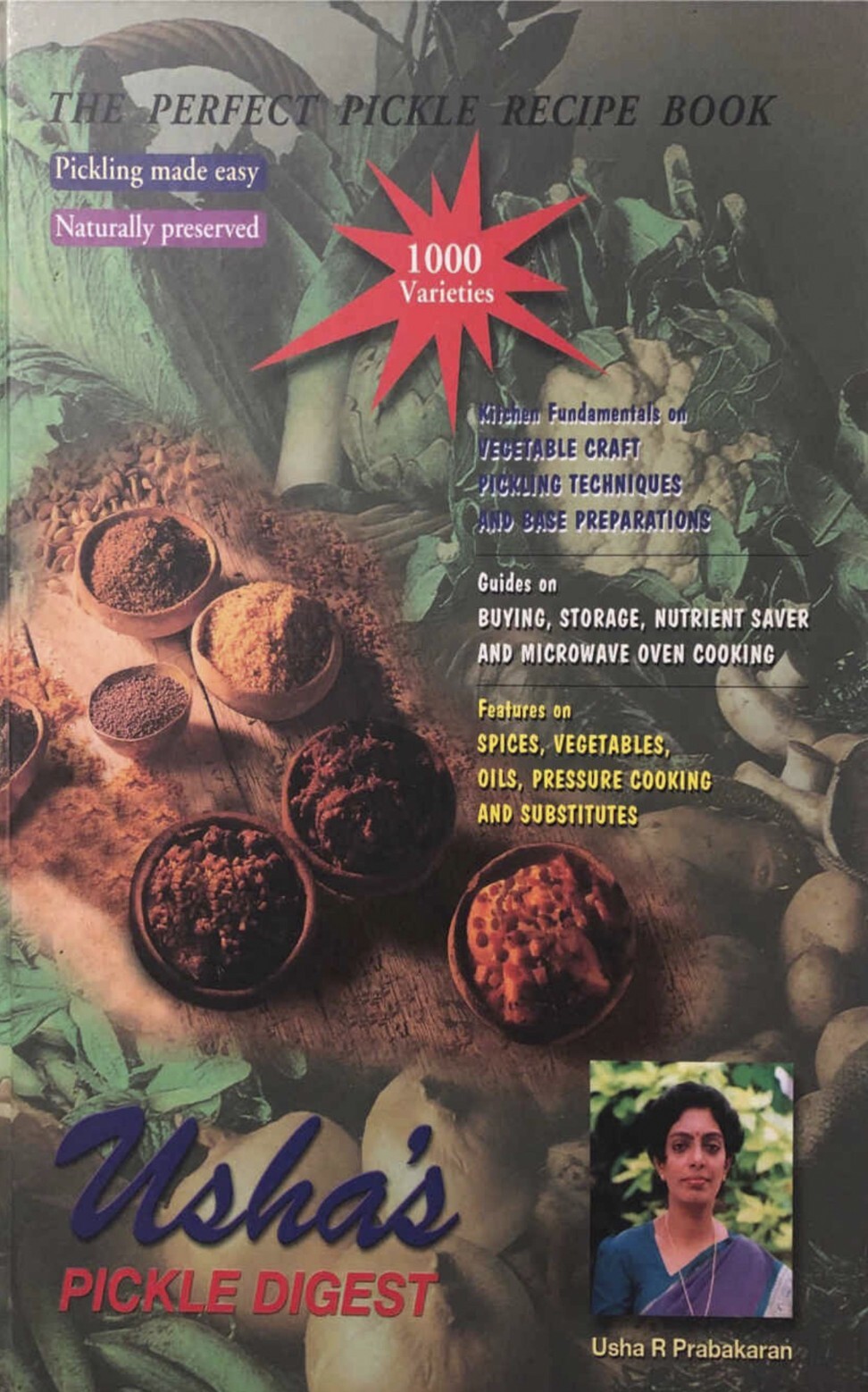

Usha Prabhakaran, a lawyer with a passion for cooking and famous for a popular book she has written on pickles, is writing a soon-to-be-published digest of over 1,000 different rasams that use everything from betel leaf to dried fruits, mushrooms and lotus stem. She says in The Indian Express newspaper that “every single thing makes a difference to the taste of a rasam, from the type of vessel used, to the ladle”.

Ashok says rasam is a no-calorie food, with a balance of all tastes – sweet, sour and hot. “The spices have medicinal value and that’s why it’s a go-to food when a person is unwell.”