Looking for the ‘Absent’ Women in Mufassal Towns of Colonial Bengal

Tania Sengupta

Confronted by the scarce imprints of Indian women in the provincial towns of 19th-century Bengal, can the evolving spatial complexity of urban domestic spaces cast light on the territorial gendering of the wider landscape, and allow us to recognise even this absence as a material presence?

1. A provincial administrative town in colonial Bengal, mid-19th century. George Francklin Atkinson, Our Station, Plate 1, lithograph, from Atkinson, Curry and Rice (On Forty Plates) Or the Ingredients of Social Life at Our Station in India (London: Day & Son, 1859). Credits: British Library Board, 1264.e.16.

By the early 19th century, the landscape of the provincial interior regions of Bengal in eastern India had fundamentally transformed. In 1765, the Mughal emperor had granted to the English East India Company the diwani – or rights of agricultural revenue collection – of Bengal’s fertile plains. The Company divided the territory into ‘districts’, each with a designated headquarter town, called zilla sadar, for the collection of taxes (fig. 1). These became the key pegs of an extensive web of British colonial revenue infrastructure that was now etched indelibly into the Bengal hinterland.

The zilla sadar’s nerve centre was the cutcherry (office) complex, consisting of the revenue-collection office, treasury, civil and magisterial courts, district jail, police and so on. Headed by European officers, the cutcherry drew swathes of Indian migrants into mufassal (provincial) towns from rural areas, moving in search of governmental employment and driven out by an increasingly impoverished rural economy. Around the cutcherry, urban life grew in European and Indian residential quarters, markets and bazars, and religious and civic institutions.

2. Ramtanu Lahiri’s house, Krishnangar, mid-19th century. Credits (survey and drawing): author.

Yet, in the narratives of these towns, for the better part of the 19th century, Indian women seem conspicuous by their absence. Despite being marginalised within colonial history, considerable headway has been recently made by feminist scholars in unearthing the lives, roles and perspectives of European women in India, with some focusing on mufassal towns and bungalow life. The presence of provincial Indian women, however, has hardly been traced, owing in part to only incidental mentions of them in men’s accounts and there being very few of their own autobiographies or memoirs in existence. I have discussed elsewhere how the provincial site was itself a marginal entity within colonial structures and within subsequent colonial (architectural) histories. The intersectional marginality of ‘the provincial’ and ‘the feminine’ makes the task of spatially locating and reading women’s presence in the 19th-century mufassal town doubly challenging. We find the stray (but still rare) autobiography of the affluent, educated upper-caste Bengali woman but hardly any trace of the large numbers of ordinary women. The mentions of provincial women’s spaces are cursory and virtually illegible, subsumed within other narratives of women in colonial India.

How, then, do we begin to figure these women within the spaces of the zilla sadar? In her queer-feminist critique of Edmund Husserl’s constitution of the phenomenological world through dominant objects and rooms, exclusions of the barely recognised and what she calls ‘co-perceived’ spaces and subjects, Sara Ahmed proposes new ‘orientations’ in gleaning new objects and sightlines of engagement. In looking for the spatial traces of women’s presence in mufassal towns therefore, their very absence needs to be explored as a type of cognitive presence. This is not merely a rhetorical or notational device. The predicament in tracing Bengali women’s presence stems from the way the zilla sadar – as a particular type of colonial site – was in its early decades fundamentally bound up with employment fed by male migration from villages into towns. This meant a physical absence of women in the sadar in real terms roughly until the 1840s. And this, in turn, mapped a larger territorial gendering across the provincial landscape.

Between the late 18th and the mid-19th centuries, the village and the provincial town absorbed a gender-split spanning across them. By the early 19th century, the main driver of the zilla sadar’s urbanisation was the new colonial administrative functions. Yet the uncertainties of an evolving infrastructure of provincial governance, as well as the cutcherry employees’ meagre initial earnings, made an outright rural-to-urban move of entire families – especially women – virtually untenable. The autobiography of Kartikeyachadra, the financial manager of the Nadia zamindar (tax collector) in the zilla sadar town of Krishnanagar, potently reveals such precarity and difficult locational choices for familial space. The provincial town thus emerged as a predominantly male space, inhabited by male family members and their male servants. Kartikeyachandra’s account, in fact, has strikingly minimal references to his wife in the village, compared with the extensive descriptions of the buoyant fun and merriment of male friendships that flourished in the town.

Reading the physical spaces of town dwellings as a type of discursive text also begins to make legible, or (counter-intuitively) ‘materialise’, the absence of women. Women’s absence can thus be read, for example, from the simple and bare-bone formations of the early dwellings of the zilla sadar. Katikeyachandra describes how he first built just a room with a veranda, and then a garden and baithak-khana (room to receive guests) and lived there well into his town employment. The provincial urban middle-class house thus represented a spatially simplified site of masculine leisure, pleasure and bonhomie. The eminent Bengali intellectual Ramtanu Lahiri’s house (built in the late 1840s) in the same neighbourhood was also a rudimentary, modest dwelling consisting of a baithak-khana, sleeping space, store and servants’ room in a simple linear arrangement (fig. 2). The absence of women therefore resulted materially in rudimentary urban domestic spaces.

3. Village homestead in Bengal, 1860s (centre/centre-left, middle distance). Typically, multiple buildings of variable sizes such as the principal hut (sleeping and storage), verandah to receive guests, maternity room, rice-husking space, kitchen, cow-shed, grain store (gola) and straw stack would be clustered together. John Edward Sache, Village Scene Around a Pond in Rural Bengal, 1865. Credits: British Library Board, Photo 44/3.

Traces of the felt ‘absence of presence’ (rather than mere absence) of women within early provincial urban houses are also detected within the affective registers that such gender-based and familial separations produced. Jogeshchandra Bidyanidhi, an eminent Bengali writer, moved as a small boy to the town of Bankura, for education, in the mid-19th century. His memoirs recall the melancholy sadness of missing his mother’s presence in their house in Bankura. Bidyanidhi also discusses how it did not have a prayer space – a vital part of his rural family home – with women as its custodians. Spaces specific to feminine use clearly did not figure within these early town dwellings. Jogeshchandra also alludes to the trauma and sadness of being wrenched out of the nurturance, shelter and symbolic space represented by his mother in the village home.

In such a reading, women’s location in ‘other’ sites such as the village home – with more elaborate and variegated spatial formations (fig. 3) – or their associations with particular types of spaces, needed to be inferred, for instance, from provincial urban spaces that omitted their presence in the first place. Through such moves, we might begin to glean fragments of the real sites and spaces that the women actually inhabited. Crucially, every absence of spatial complexities or of specific types of feminine spaces in the towns also qualified the male town dwellings in particular ways. It is therefore impossible to read provincial early-urban domestic spaces without referring to the pregnant absences of feminine spaces that they carried.

Nitin Sinha suggests that histories of migration have for too long focused on mobilities and mobile agents and hence has privileged men who, in 19th-century northern and eastern India, moved in circulatory patterns between the village, the town and further afar. Sinha urges that histories of migration need to narrate the stories of immobility alongside the stories of mobility. In the context of zilla sadar towns, due to their itinerant linkages with villages, the Bengali migrants’ domestic world also straddled two sites – the rural ancestral home (bari), the stable rooted place anchored by women; and the town dwelling (basha), the notionally transient (although in reality often long-term) space associated with colonial employment. Hence categories such as female-male, rural-urban and bari-basha effectively represented contiguous, connected, co-constitutive couplings and closely mapped onto each other.

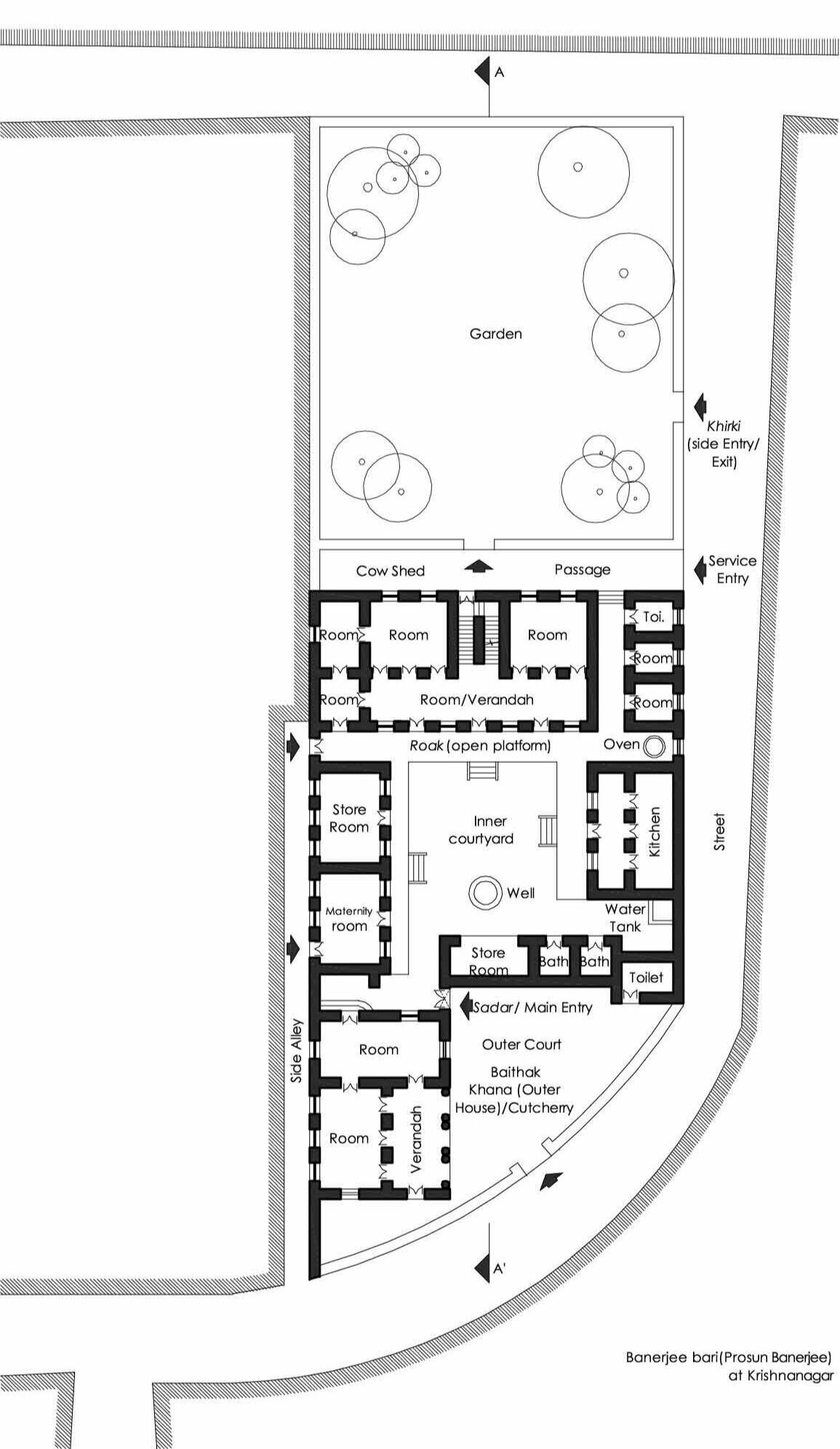

4a (photo) and 4b (plan).

Banerjee house, Goari, Krishnanagar. The baithak-khana (4a, left) was built in the 1860s as a multipurpose space for male family members. The inner house (4a, centre) and other female-oriented structures surrounding the interior courtyard were built by the late-19th century. Credits (survey, drawing and photo): author.

From around the mid-19th century, a number of factors influenced the increasing movements of families and women into mufassal towns: the continuing marginalisation of villages; some consolidation of personal finances; Governor General William Bentinck’s reforms of 1835 privileging English and Hindustani in administration; Indian reformer Ram Mohan Roy’s educational reforms; and better urban medical and educational infrastructure. We read their imprints, particularly from the 1860s, in a new type of spatial complexity and urban domesticity. The outward-oriented baithak-khana of the Banerjee house in Krishnanagar (figs. 4a and 4b), for instance, was a clearly urban gesture, while its interior absorbed many aspects of rural familial and feminine life, rituals and space, with more buildings intricately gathered together and substantial proportion of spaces (e.g., inner house, maternity rooms, shrines, kitchen and storage) primarily used by women and/or servants.

Given the paucity of textual records, the material imprints of urban domestic space thus contained figurations of both the absence and the presence of women in the mufassal towns of Bengal over the course of the 19th century. However, these figurations become legible only through a careful re-‘orientation’, gathering faint traces and recognising even absence as a material presence.

FURTHER READING

Sara Ahmed, ‘Orientations: Toward a Queer Phenomenology’, GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 12.4 (2006), 543–74.

Swati Chattopadhyay, ‘Goods, Chattels and Sundry Items: Constructing 19th-Century Anglo-Indian Domestic Life’, Journal of Material Culture 7.3 (2012), 243–71

Rassundari Dasi, Amar Jibon [My Life] (Calcutta: College Street Publication, 1987 [1876]); Prasannamayee Debi, Purbakatha [Tales of Yore] (Calcutta: Indranath Majumdar, 1982 [1917]).

Lal Behari Dey, Bengal Peasant Life; Folk Tales of Bengal; Recollections of My School Days, ed. by Mahadevprasad Sinha (Calcutta: Editions Indian, 1969 [1878]).

Atig Ghosh, ‘The Mufassal and the Modern: The Discreet Charms of Kangal Harinath’, in Modern Makeovers: Handbook of Modernity in South Asia, ed. by Saurabh Dube (New Delhi: Oxford University Press India, 2011), 76–92.

Jane Haggis, ‘White Women and Colonialism: Towards a Non-Recuperative History’, Gender and Imperialism, ed. by Clare Midgley (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998), 45–75

Mary Procida, ‘Feeding the Imperial Appetite: Imperial Knowledge and Anglo-Indian Domesticity’, Journal of Women’s History 15.2 (2003): 123–49

Kartikeyachandra Roy, Diwan Kartikeyachandrer Atmajibani [Diwan Kartikeyachandra’s autobiography] (Calcutta, n.d. [1840s]).

Tania Sengupta, ‘Between Country and City: Fluid Spaces of Provincial Administrative Towns in Nineteenth-century Bengal’, Urban History 39.1 (2012): 56–82.

Nitin Sinha, ‘The Idea of Home in a World of Circulation: Steam, Women and Migration through Bhojpuri Folksongs’, IRSH 6.3 (2018), 203–37

Tania Sengupta is Associate Professor at the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London. Her research looks at the history of architecture and urbanism of South Asia from a transcultural and postcolonial perspective. Some of the research themes are spaces of colonial governance; provinciality and rural-urban relationships; spatial patterns of domesticity; social relationships of architectural expertise; and architecture, material cultures and people’s everyday lifeworlds. Her research on spaces of paper-bureaucracy in colonial India was awarded the 2019 RIBA President's Award as well as the President's Medal for Research. She is co-chief editor of the journal Architecture Beyond Europe.