If a daughter were looking for a place to explore the joys and complexities of her relationship with her 79-year-old father, Varanasi, the holy city in northern India, would not be a bad spot to land. After all, it’s said that the Buddha gave his first post-enlightenment sermon just a few miles outside of town. And if that father happened to be Raghu Rai, the single-most revered photographer in India’s history, and that daughter was 29-year-old Avani Rai, herself an emerging photographer, filmmaker, and artist, then Varanasi’s mystical setting—dark-eyed sadhus cloaked in saffron robes sit on the banks of the Ganges, thousands of tiny altars splashed with flower petals dot the side streets—would offer plenty of moments to light up their cameras. Of course, it would also provide an opportunity to, quite literally, see the different ways that parents and children look at the world.

While the father has, of course, known the daughter since she took her first breath, the two have never before shared a photo assignment. And so they have traveled to Varanasi to shoot together, learn from each other, and maybe even grow a bit closer.

BEHIND EVERY PICTURE

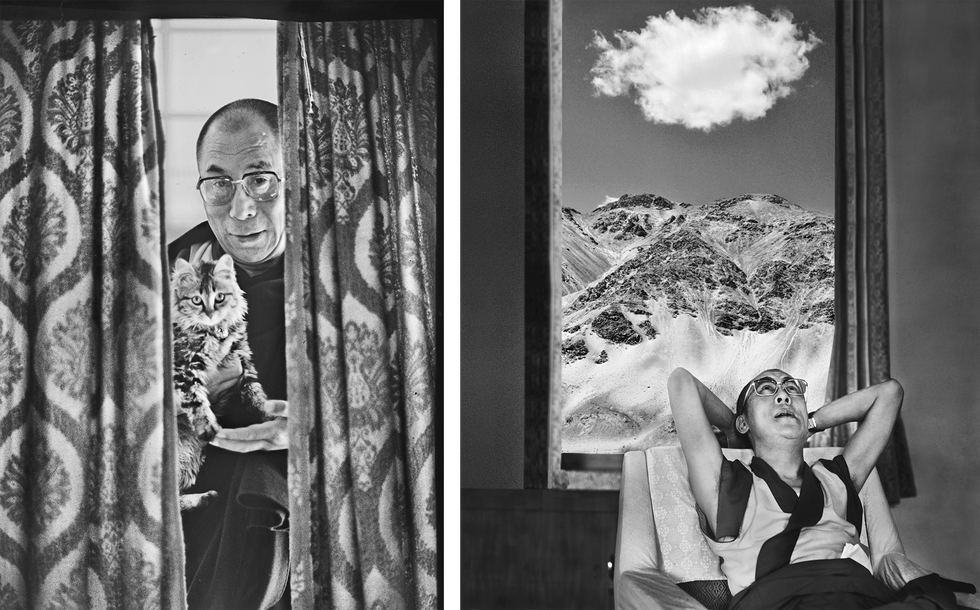

As Raghu and Avani squeezed, bumped, dodged, and shimmied through Varanasi’s tilt-a-whirl streets, as their cameras sized up snake charmers, acrobats, and boatmen, quieter dramas were playing out behind the lens. How, for instance, would Avani walk the narrow path between listening to her father’s hard-earned career advice—the man has taken world-famous portraits of Mother Teresa and the Dalai Lama—while trusting her own creative vision? How persistently would Raghu nudge his daughter to sidestep mistakes at the expense of letting her learn her own lessons? And would this parent-child-student-teacher friction end up pushing them apart or pulling them together?

Raghu: I want my child to inhale, to experience all the richness that is there in this world. But I am a not a patient man. How I wish that everything I have learned in 55 long years as a photographer you can know within three years.

Avani: You are always in a hurry! Not long ago, I would be like, "Stop telling me how to shoot. I know you're very well established. I know you're super cool, but I'm not you."

Raghu: We had lots of confrontations. You would say, "Papa, This is my work. Leave me alone!" And you—

Avani: I would say it without even knowing who I was, or what I believed in. It was just rebellion. But now when I'm shooting, you know, I take the photograph you would want me to take and get it over with.

Raghu: Oh?

Avani: Then I will take the photograph I want to take. I make you happy, I make myself happy. Sometimes they are both the same image.

Raghu: Once in a while you listen to me, but while shooting you forget it. Which is actually very good because you have great instincts.

Avani: I mean, it’s not like you’re speaking in my head—my own voice is so loud when I’m shooting—but sometimes I find you in the viewfinder. I look and I know it's your image. It’s like, “Oh my God, that is his!”

Raghu: If you respond instinctively to what you see, that gives you the truth—and you can capture the spirit of the situation in this moment. And this moment is precious, no? It is always coming and disappearing, you know?

Avani: Papa, the whole idea of finding an extraordinary moment in a very ordinary situation, a moment that means something, a moment that stays—you’ve given that to me. I know it would have taken a couple of decades to learn that if it wasn't for you fighting with me. Or me fighting with you.

Raghu: Sometimes I try to talk to you about what makes a strong image but, you see, the thing that is so beautiful about this girl is that she's on fire. When you’re shooting, Avani, you don’t want to talk. You don’t want to meet people. You don’t want to do anything else. You are focused and on fire.

Avani: Papa, you don’t tell me that…

Raghu: You are instinctively picking up moments that become very relevant, very meaningful. You have great instincts, but you do not have enough discipline. What I have learned—

Avani: We are going to have the same arguments forever, I think. Varanasi was just stressful enough and peaceful enough for us to be together but still do our own thing. When I’m shooting in Kashmir it is different. [Kashmir, in India’s far north and the only region in the country with a Muslim majority, has seen years of political and religious unrest, which has sometimes turned violent.] I complain to my mother: "Tell him to stop asking me to come back home. I'm not having an affair. I’m not messing around with some boy. I'm not doing frivolous stuff. Why is he telling me to come back home? I’m shooting!"

Raghu: You see, the Kashmir situation is very dangerous and anything can happen. A terrorist attack can happen suddenly. So I would like you to do what you want to do, what you are committed to, but when you’re in Kashmir, my heart is in my mouth.

Avani: I shoot in complex, political situations because I feel like that is our responsibility. And that's something that comes from you.

Raghu: You’re remarkable. But you’re also my baby, so sometimes I have to keep my eyes on you.

THE COMPETITIVE SPIRIT

In Sanskrit, Varanasi is known as the City of Light, and a photographer would have to spend a couple of lifetimes here before running out of things to shoot. Sunrise silhouettes of wooden boats crossing the Ganges? Click. Wandering goats. Flower markets. Funeral pyres. Clean-ish hotel sheets drying on not-so-clean-ish steps. Click, click, click. But which are the images that perfectly capture the essence of a moment? This is the split-second magic that photographers spend years training their eyes to see—and what they are forever competing for. And if you thought that the spirit of competition didn’t extend to a father and daughter wandering an ancient city, you have missed the point.

Avani: I'm quite competitive actually. You are not, of course. You find it funny that I compete with you, but—

Raghu: In Varanasi, whenever I took a good picture and showed it to you, you said, "Papa, you can't do this!" I said, "But it's happening. What to do?" You feel very competitive, which is good. I love it.

Avani: Yeah, it was quite a fight. Remember the rain pictures?

Raghu: Why are you calling it rain! It was a hail storm!

Avani: It was mad! We woke up early to see Varanasi from the river. The whole city comes to life in the morning, with all the people and the colors.

Raghu: We had just gotten in the boat and had barely started moving down the river when I saw the dark clouds. I started to say, “It looks dangerous.” Before I finished speaking, the storm had begun. I was the last one out of the boat and was drenched. You ran away and—

Avani: I was hiding! But this became a funny moment, actually, because we were completely soaked, my camera was wet. I said, "I'm freezing! I'm going to go to the hotel to change my clothes." You were, like, "We are photographers! We keep shooting!" So then I seemed like a loser and—

Raghu: I continued taking pictures.

Avani: You were running around in this rain like a 12-year-old, shooting, not caring. I was with four strangers, standing under a large umbrella, and mostly shooting what was in front of me. At that point, I thought I had lost.

Raghu: Later, when I saw your horizontal frame I said, "Wow! What an image!"

Avani: You kept looking at that picture, and were really proud of it. I remember you said, "You got the better one."

Raghu: That’s right.

Avani: So it was a competition! Every time we shoot together it's always a competition. I won that particular one.

Raghu: You’re my child; when you win, I feel better.

THE ROOTS OF PASSION

Did Avani find her passion for capturing lasting images from staring at her father’s fresh-from-the-darkroom prints drying on the backyard line—or was it already living in her genes, a predisposed way of looking at the world she couldn’t escape even if she’d wanted to? Impossible to know for sure, of course, but this father and daughter have a long history of a camera between them—though not always carefree.

Avani: You had turned the bathroom downstairs into a darkroom and when I was very young, there would be prints everywhere—on the dining table, on the sitting area, all over the floor. I remember making a game out of jumping between one print and another and not stepping on them. But I’m sure I must have stepped on some of them.

Raghu: All of them.

Avani: There was not a single day where we wouldn't see the camera. It was daily life, like eating food, like having a bath. In my teenager years, I was having the ugly phase of life, and I was like, "Stop shooting me all the time! Take this camera away from my face!"

Raghu: This is true. I spent years photographing many great people, the Dali Lama, Mother Teresa. And when I’d come home, I’d share everything, and the children would listen.

Avani: I remember—

Raghu: But I can't say that because your father is a photographer, you have become a photographer. I think this was born out of your personal need to see the balance of beauty and justice, which is very important.

Avani: I didn't want to be a photographer, you know. But I had never been away from home before so when I went to college [in Mumbai, nearly 900 miles away from her parents’ home in Delhi], you were like, "Okay, you're leaving, whatever, you can use this." And you gave me an old camera you had stopped using.

Raghu: It wasn’t so old.

Avani: I knew nothing about cameras. I wasn't looking for the right frame or wanting to be a filmmaker. None of that. But when I’d come home for the weekend, you would do these silly, sweet, lame things for the camera and everyone would laugh. I would use the camera to basically keep a memory. I’d get back to college and watch those moments again and again. They connected me.

Raghu: I must say one thing. The spirit and the energy of the parents gets into the spirit of their children. I'm a very emotional person. So are you.

Avani: When I started visiting Kashmir in 2014, I wasn't even a photographer. As I met more and more people there, I felt like, “They so far away from the rest of the world. This is a place that people just don't know!” And I started taking stills.

Raghu: Sometimes you would come up with simple, powerful images. Then I’d begin to say, "Yes, yes, that makes sense." It happened gradually over the years. Not right away. I wouldn’t say, “That’s wonderful!” You know, I'm very tough on myself. And on you.

Avani: Yes, I know this.

Raghu: I have realized that children think whatever their parents’ profession is, they can do it easily. But when you started showing strong work, I said, "Baby, that is something." You said, "Thank you, Papa. At least you have said this to me once."

EVERYTHING IN FOCUS

Looking at the world through a camera actually teaches you to see—see more beauty, yes, and sometimes more suffering, but also how objects in space speak to each other, how a street sign and a baby carriage and a balloon fit together in an instant to make a memorable picture. This can lead to an at-one-with-the-world glimmer, a hundredth-of-a-second version of the fabled “runner’s high.” Even for weekend camera-slingers, watching life through a viewfinder can enhance one’s connection to a city, its inhabitants, the people you’re sharing the experience with.

Avani: There are so many worlds in Varanasi, and every space can be experienced and explored in so many ways. You can get lost in the spiritual aspects of the place, its colors, the emotions, the way the city is designed and not designed, its clutter and chaos, all kinds of good and evil. So many worlds in one world.

Raghu: Varanasi is like Mecca for Hindus. Pick up a stone, and you'll find a God underneath.

Avani: I can become overwhelmed in a place like this and the camera calms me down. You hold it and focus on one thing: "This is what I have, this is what I'm connecting with."

Raghu: Sometimes, watching you shoot, I feel breathless: Why isn't she moving into the larger space? An understanding of the space comes with a lot of experience, because moments we can choose easily, emotions we all get touched by at the same time, but to put it all in the right kind of space? That is everything.

Avani: You used to tell me, "You should be searching. Even if you don't know what you're searching for, you need to be searching all the time." I would be like, "What are you saying, man? It doesn't even make sense!” But now it makes complete sense.

Raghu: It’s an instinctive journey.

Avani: To be able to find an image, a photographer really has to be in the moment. Papa, you’re very layered as a person and as a photographer. There is something happening in every inch of your pictures. What you see is much more nuanced than what I see.

Raghu: Sometimes I feel I'm too complicated. And in a way, you have influenced my photography.

Avani: Really?

Raghu: Sometimes now I take pictures without looking through the viewfinder to be a little more free-flowing in terms of space and angle. That's not really 100 percent me.

Avani: Basically all of our arguments, all the heat, is just because of a point of view. So when we’re together and have a moment to see each other shoot, that is an experience in itself. But then, later, when we’re looking at the photographs together, we can each see something different, maybe something we didn’t see before.