The Indian government has plans for large-scale electricity generation projects, and is moving to allow an increased role for private companies, domestic and foreign, in the nuclear energy industry. But it is doing so without strengthening the legal framework covering compensation, liability, classaction and the ability to deal complex tort cases. The failure of litigation attempts properly to call Union Carbide to account for the gas tragedy at Bhopal suggests lessons that need to be learned if a legal framework is to be created which will be able to address the possible eventualities arising out of the use of nuclear energy.

India originally used nuclear energy for various social applications including energy generation through the framework provided by the Atomic Energy Act, 1962. Initially, the Atomic Energy Act provided exclusive government control. The concept of public participation was introduced later, and there are now plans gradually to open up the nuclear energy generation sector to full private participation.

Implementation of the Indo-US Joint Statement of July 18, 2005 ended India's isolation over the peaceful use of nuclear energy. It also served to turn the spotlight away from major loopholes in the Indian legal system such as environmental protection, rehabilitation, liability and compensation and transparency.

Now the Indian government has decided to introduce in the Union Parliament’s Budget Session a piecemeal legislation called “Nuclear Liability Bill’ to cap the liability from potential accident. This article examines the legal issues raised by the Indo-US Nuclear Cooperation Agreement and the ability of the Indian legal system to address the issues associated with nuclear energy in the light of the experience gained from the Union Carbide (Dow Chemicals) Disaster at Bhopal.

Why Legal Framework?

A legal framework is important for the following reasons

1) Domestically a well developed legal framework covering the peaceful use of nuclear energy will foster development as well as address the problems raised by the industry especially those affecting the public.

2) Internationally it is a prerequisite for engaging in nuclear cooperation and technology transfer.

It will be beneficial to analyse the legal framework in United States and France with which India entered into Nuclear Co-operation Agreements. The gradual operationalisation of the agreements allows nuclear firms from these countries to operate without an adequate legal framework in India, while their activities are highly controlled in their home state. This brings about a situation akin to that which opened up for multinational corporations when the World Trade Organisation was established to exploit the availability of cheap labour, rich resources and inefficient legislative, legal, administrative and enforcement mechanisms. The impact of any potential hazard from the nuclear industry to the public and environment will be much higher. This in itself highlight the need to provide a legal framework covering all aspects of peaceful use of nuclear energy.

The legal framework in the US and France, unlike that in India, covers all aspects of the peaceful use of nuclear energy, especially through liability and compensation, public participation and transparency. The Price Anderson Act, for example, which was an amendment to the Atomic Energy Act, 1954 provides a unique system of nuclear liability coverage for power plants as well as for the transportation of nuclear materials to and from such facilities. It covers all losses of third party bodily injury and property damage off the site of the nuclear installations. Beyond the insurance cover and irrespective of fault, Congress, as insurer of last resort, can decide how compensation is provided in the event of a major accident. The 1966 Amendment to the Act provided for the establishment of an Extraordinary Nuclear Occurrence (ENO) for liability and also the concept of precautionary evacuation. The National Environment Policy Act (NEPA) and the Alien Torts Act further strengthens the legal framework.

The French Nuclear Programme, unlike that of the United States, is based on substantial involvement by the government in both the development and production of nuclear power. It has a liability cap and uses a single reactor system design for uniform safety systems. The liability constraints in France are based on a variety of international treaties. France adopted and modified both the Paris and Brussels Conventions in its Law on Third Party Liability in pursuant to the Paris Convention, Brussels Convention and Additional Protocols of 1964 and 1982. The major areas covered by the Act include summary procedure for getting compensation and a special tribunal with power given for emergency measures to the Public Prosecutors and The Examining Magistrates.

Another peculiar legislation is that concerning the democratisation of public enquiries and environmental protection to inform the public and obtain its comments, suggestions and counter proposals. The 1987 Act clarifies the pre-existing system of assistance, organisation plans and emergency plans to introduce more information about major risk with increased obligation to the operator for safety and risk. Article 1384.1 of the Code Civil provides an escape from liability only if the accident occurred due to force majeur or unforeseeable circumstances.

Legal Framework for the Use of Nuclear Energy in India

The Constitution of India includes the subject of atomic energy and its mineral resources in the Union List providing the Central Government exclusive control over nuclear energy. The Atomic Energy Act was enacted in 1948 and replaced in 1962 with an Act which empowers the Central Government and in turn to the Atomic Energy Commission, to do all things associated with the use of nuclear energy.

The Atomic Energy Act does not specifically deal with the question of compensating nuclear damage. Section 29 of the Atomic Energy Act of 1962 provides that; “No suit, prosecution or other legal proceeding shall lie against the Government or any person or authority in respect of anything done by it or him in good faith in pursuance of this Act or of any rule or order made under.”

This provision seems to confer immunity from legal action. In the case of a nuclear incident causing radiation exposure to the public and environment the Government will resist a claim of compensation and liability. With the approval of private firms in this area, the present legal framework’s ability to address these issues becomes yet more important.

Rhetorically it can be said that judicial activism in the field of Article 21, Constitution of India has expanded the concept of right to life and personal liberty. The Indian judiciary was able to develop compensatory jurisprudence based on Article 21 and principles like the absolute liability principle.

Developments related to Article 21 of the Constitution of India will limit the application of section 29 of the Atomic Energy Act conferring immunity on the government. But this must be considered in the light of the justice rendered to the victims of the Union Carbide Tragedy at Bhopal. This highlight the weakness of the present legal framework to provide liability, damages and even to bring those responsible for trial. Under the present legal framework, the impact of a major nuclear incident will be catastrophic. It will raise complex tort litigation which could take decades.

Union Carbide Gas Tragedy: Unsettled Issues

The Union Carbide tragedy at Bhopal remains an outstanding example of the failure of the judiciary, government machinery and certain sections of the civil society to provide justice to the victims as well as to future generations due to inefficiency and the lack of a proper legal framework.

The experience gained from the aftermath of Union Carbide Tragedy becomes increasingly important as India enters the nuclear foray without a proper legal framework and with an underdeveloped compensation and liability regime.

Union Carbide opened its Bhopal Plant in 1968. On the night of December 2nd -3rd 1984, methyl isocyante, hydrogen cynide and other toxic gases began to leak in substantial quantities from the pesticide factory of Union Carbide India Limited (“UCIL”) in Bhopal, India. Though government figures are lower, it was estimated that around 8,000 people died in the course of 3 days of leakage. The effects were profound on the surviving population.

The Indian government passed the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster (Processing of Claims) Act, 1985 making itself the exclusive representative of the Bhopal victims and filed "unprecedented" claim in the United States Court against Union Carbide Corporation, the majority shareholder in UCIL. The case was unique, since India; a sovereign republic representing thousands of indigent victims was asking the United States judiciary to determine the liability of a Multinational Corporation. The Indian claim was to hold the parent corporation absolutely liable for foreign harms regardless of whether it was a subsidiary or head office that caused the harm, since the Multinational Corporation was in the best position to prevent those harms in its profit making enterprises.

Moreover India also argued that its laws were not developed to handle this mass tort litigation and the legal argument was based on three situations. Namely that 1) Indian legal system is inadequate for the litigation, 2) Union Carbide by its control of UCIL was responsible for the acts of its subsidiary and 3) there is overwhelming American interest in encouraging American multinational corporations to protect the health and well being of peoples throughout the world.

Union Carbide requested the US court to dismiss the action on the ground of Forum Non Conveniens, pleading that India was the appropriate forum. The district court hearing the consolidated action resulting from these suits ultimately dismissed the case under the doctrine of forum non conveniens. This was upheld by the second circuit, which effectively denied the plaintiffs an opportunity to vindicate their legal rights in the U.S. federal courts. The decision by Justice Keenan reasoned that the dismissal would best serve US public interest factors.

After the case was dismissed in the U.S, the Government of India brought a $ 3 billion claim against Union Carbide in India. In the mean time the assets in India were sold and the money donated to build a hospital to treat victims. With regard to the liability of Multinational Corporations for the actions of its subsidiary, the interim order reached by the Bhopal District Court and the Madhya Pradesh High Court needs special emphasis, as it deviated from the perceptions held in Judge Keenan’s decision.

When the issue came before the Supreme Court of India, it failed to acknowledge the established legal principles. It also failed to pick up on the novel concept of treating businesses tightly interconnected as a single entity by piercing the corporate veil which was advanced by Judge Seth of Madhya Pradesh High Court. The Indian government agreed to an out-of-court settlement of $470 million USD in February 1989 as the full and final settlement of all civil liability.

There were cases challenging the constitutional validity of the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster (Processing of Claims) Act 1985, which gave the Indian central government exclusive power to represent the victims in all legal proceedings on the grounds that it made no provision for a hearing violating natural justice. Even though the Court upheld the constitutional validity of the Act, it does not clearly distinguished the validity of the Act and the settlement judgement.

The settlement order was challenged in a review petition. On review, the Supreme Court upheld the settlement but reinstated the criminal charges against UCC, UCIL and several officers including UCC Chief Executive Officer Warren Anderson. None of the accused appeared before the Bhopal courts to face criminal trial, even though before the US District Court the UCC showed its submission to Indian Jurisdiction. The court declared UCC, UCIL, Warren Anderson and other indicated officers as absconders from justice. But no creative step like extradition proceedings were initiated, as was the case with the extradition of the "Natwest Three" from England to face charges in the US regarding the collapse of Enron. This demonstrates the inability of the Indian Judiciary and Government to deliver justice to the victims.

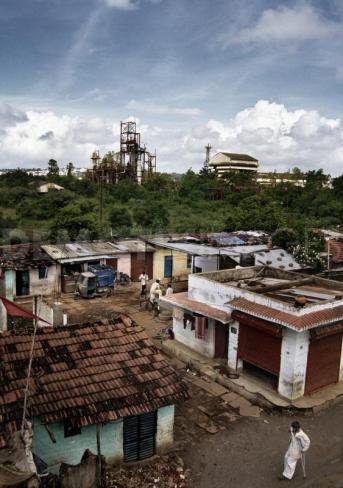

The Union Carbide never provided the information regarding the composition of the leaked gases or its impact on human and environment. The factory was abandoned leaving behind large quantities of toxic waste causing health hazards to the population around it, birth defects to even second generation of children and groundwater pollution. In 2001 Union Carbide merged with Dow Chemical making Dow Chemical the largest chemical company in the world. Dow has refused to accept the moral responsibility for the actions of Union Carbide in Bhopal. In the US there are cases still ongoing regarding its legal responsibilities. Meanwhile, the local population of Bhopal continue to suffer the contamination left behind by the disaster.

Recently the Bhopal District Court has issued an order asking U.S.-based Dow Chemical Corporation to explain why it should not be required to have its subsidiary, Union Carbide, appear to face pending charges in a criminal case relating to the 1984 gas explosion which killed thousands of Bhopal residents. To escape from the issues of legal liability the Dow Company is now trying for an out of court settlement regarding the cleaning up the UCC’s abandoned Bhopal plant, while at the same time distancing itself from the UCC’s liability.

The leakage at Bhopal provides three points namely 1) the absence of legal framework for dealing multinational corporations as it was not subject to the law of its home state (United States) or its host state (India) or to international law 2) the inability of the Indian judiciary and legal profession to handle complex tort cases and 3) the extreme delay in providing justice (in its fullest sense). Moreover it also highlights the ability of the multinational corporation to escape civil and criminal liability and at the same time its ability to lobby the government machinery for escaping from cleanup costs and to continue its business. .

Conclusion

Currently it is difficult to bring class actions under civil law and the law of torts is underdeveloped when compared with position in other states using nuclear energy. Moreover together with other issues like delay in deciding cases, restrictive approach of courts towards compensation amount, ability of the Indian legal profession to handle complex tort cases, difficulty in access to the Indian Judicial System and the need for scientific and medical evidence makes litigation in the area of nuclear damages virtually impossible for an average Indian.

The Indian government’s approach presently focuses only on maximalising the use of nuclear energy through commercialisation. Private firms are being added into the equation without any legal framework to deal the eventualities arising out of the use of nuclear energy.

An updated legislative framework is required to accompany the policy change regarding the increased use of nuclear energy together with the entry of private companies, both domestic and international. The present plans to introduce a bill in parliament to cap the liability from potential accident does not address the other issues connected with the peaceful use of atomic energy.

The only way the government can allay public fear regarding the use of nuclear energy is for it to introduce a comprehensive legal framework relating to the use of nuclear energy. This must meet issues of liability regime, compensation, public participation in decision making, waste disposal and environmental protection and relief and rehabilitation. Other wise the common man will be left to suffer the consequences. In the long term, the result would be violence and the kind of collapse of law and order which has resulted from opposition to mining and industrialisation in the eastern states of India.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.