The end of a 520-day simulated mission to Mars marks one more step in a succession of make-believe trips to Mars, leading up to the real thing. And who knows? You might even be able to get in on a "sim."

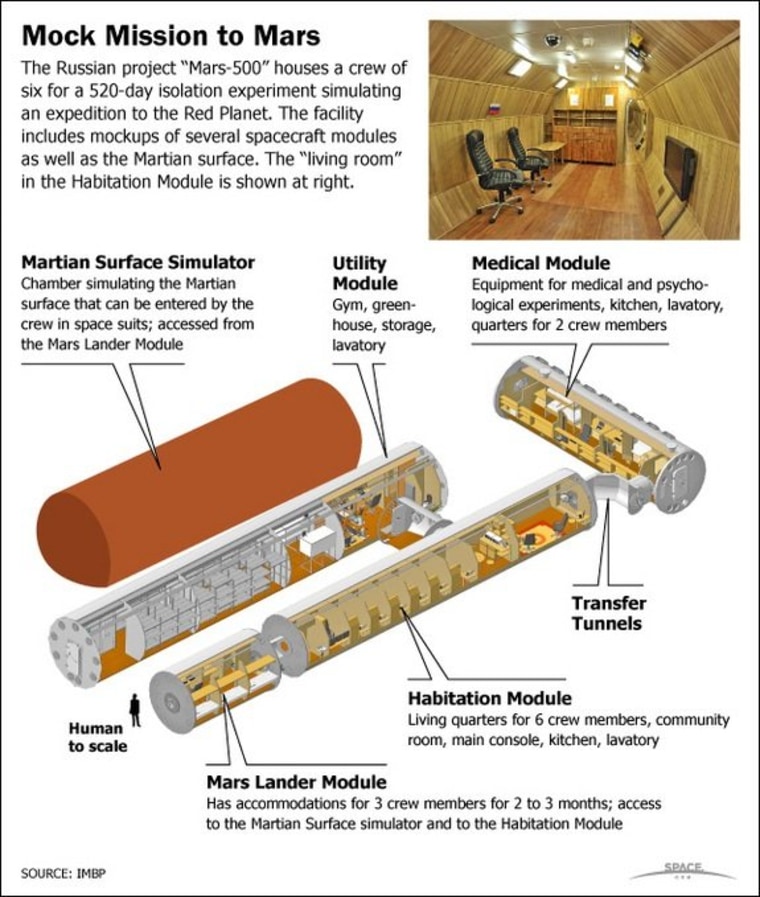

Measured by length and expense, the Mars500 exercise is the most ambitious earthly simulation to date: In June of last year, the $15 million experiment put six male volunteers from Europe, Russia and China in a windowless mobile home that was set up inside Moscow's Institute for Biomedical Problems. Crew members "landed" at their destination in February, and walked out into a make-believe Mars roughly the size of an indoor tennis court.

After a months-long simulation of the return trip, the crew is scheduled to "land" back on Earth on Friday and climb out of their isolation compartment. "The longest night in the world is about to finish," simulation crew member Diego Urbina wrote today in a Twitter update. You can watch the hatch opening via the European Space Agency's website at 6 a.m. ET (11:00 CET).

'We come in peace'

The whole idea of this simulation was to see what kinds of interpersonal problems might come up during a real 520-day mission to Mars, due to the confined space, delays in back-and-forth communication, once-a-week showers and the sense of separation from the home base. If the aim was to see whether a six-person team could survive the simulated trip without lashing out at each other, this team passed with flying colors.

"They have had their ups and downs, but these were to be expected," Patrik Sundblad, a life sciences specialist at the European Space Agency, said in an online recap of the mission. "In fact, we anticipated many more problems, but the crew has been doing surprisingly well. August was the mental low point: It was the most monotonous phase of the mission, their friends and family were on vacation and didn't send so many messages, and there was also little variation in food."

The crew's spirits lifted with the approach of the end, and Urbina could indulge in a little space levity as the final hours ticked by. "'We come in peace' ... I always wanted to say that," he wrote.

But this simulation left out some of the most important challenges that would face real Mars-bound astronauts: for example, the bone and muscle loss that comes along with spending months in zero gravity, and the risk posed by radiation exposure between here and the Red Planet. Some of those issues will be addressed in the simulated Mars missions to come.

Simulations in space

The biggest and most expensive "simulation" of a mission to Mars isn't a simulation at all: It's the multibillion-dollar operation known as the International Space Station. This month marks 11 years of continuous human presence aboard the station, and during all that time, much has been learned about coping with weightlessness. (One big problem that's come up is vision impairment. Possible coping mechanisms: artificial gravity and hibernation.)

The next few years are expected to bring additional experiments aimed at testing the waters for Mars missions. NASA has been talking about setting up time delays in Earth-to-space communications, to reflect the minutes-long light-speed travel times between Mission Control and a spaceship heading for Mars. A 10-minute time delay is on the space station's tentative science agenda for next year. Several experts have suggested attaching prototype Mars modules to the station for future test runs.

Russian space officials are thinking about conducting a Mars500-style experiment aboard the space station sometime after 2014, the Itar-Tass news agency reported today. "We are interested in staging such an experiment in actual conditions of zero gravity," Vitaly Davydov, deputy chief of Russia's Federal Space Agency, told Itar-Tass. "It is too early to say when such an experiment could be made."

If the plan goes forward, at least two astronauts would spend at least 18 months in orbit. That timetable is much longer than the typical four- to five-month tour of duty — and would set a new record for time spent in space. The current endurance record is 437 days and 18 hours, set in 1995 by Soviet cosmonaut Valery Polyakov aboard the Mir space station. Polyakov was said to suffer some low moods during his record-setting stint in space, but there were no lasting physical impairments, and by all accounts he's still healthy at the age of 69.

"I was able to stand up and walk on Earth after being in zero gravity," he told an interviewer at the New Mexico Museum of Space History in 2007, "so it should be easy to stand up and walk on Mars."

Experiments on Earth and Mars

More make-believe Mars missions will be getting under way here on the home planet. Next month, the nonprofit Mars Society will begin its 11th field season at the Mars Desert Research Station near Hanksville, Utah. Teams of volunteers cycle through tours of duty at a lonely-looking habitat in a Marslike desert environment. Part of the job is to go out in faux spacesuits and simulate surface exploration, but there are also experiments aimed at testing technologies and procedures that could come into play during a real Mars mission.

The deadline has passed for this season's crew selection, but if you want to volunteer, there's always next year. If you're selected to participate, you'll have to pay a fee and cover some of your travel expenses. The project's organizers also say you'll definitely have a "leg up" in the selection process if you're working on a research project that could yield publishable results.

During the summer, the Haughton-Mars Project provides a home away from home for researchers on Devon Island in the Canadian Arctic, one of the most Marslike places on Earth. Researchers from around the world have conducted Mars analog experiments at Haughton Crater for more than a decade.

So what about the real Mars? NASA's timetable for human exploration calls for astronauts to visit the low-gravity moons of Mars in the mid-2030s, followed by forays to the planet's surface. There's lots to be done between now and then, not only to solve the challenges facing interplanetary space travelers, but also to do the robotic reconnaissance that's required in advance of human missions.

Two robotic missions are set to blast off toward the Red Planet in the next month: Russia is due to launch its Phobos-Grunt probe from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan on Nov. 8, with a landing on the Martian moon Phobos expected in 2013. NASA's Mars Curiosity rover arrived at its Florida launch pad today, in preparation for a Nov. 25 launch.

And then what? Some observers worry that NASA's budget woes will put a huge crimp in planetary exploration, including future missions to Mars. Scientists would love to have samples of Martian soil returned to Earth for study, but the crystal ball seems to be providing less clarity as time goes on. Will we be stuck in simulation mode forever? Feel free to weigh in with your comments below.

More about Mars:

- Citizen scientists: Help find life on Mars

- Slideshow: Greatest hits from Mars

- 'Red Dragon': A cheaper search for life on Mars

- Cosmic Log archive on Mars

Connect with the Cosmic Log community by "liking" the log's Facebook page, following @b0yle on Twitter or adding me to your Google+ circle. You can also check out "The Case for Pluto," my book about the controversial dwarf planet and the search for other worlds.