Bahrain lacks land, so it's building more: lavish artificial islands

The Persian Gulf nation’s plan will double its land mass—at a steep cost to its vibrant marine life.

In the fishing village of Karranah on the north coast of Bahrain, 72-year-old Haji Saeed, one of the community’s oldest fishermen, wades through the low tide to check his traps.

Twenty years ago, the sea in front of him was home to an abundance of local fish, including hamour, a type of cod, and safi, a rabbitfish; he could easily catch over 100 kilograms (220 pounds) in a day.

Then, the Bahrain government built two artificial islands that altered the seabed, driving fish populations away from the shallow coastal waters.

When he returns to shore, Saeed has collected barely more than three kilos (6.6 pounds) of fish from his five traps, called hadrahs. The next day, he collects only three fish weighing just half a kilogram, slightly more than one pound.

“It’s been like this ever since the islands were made,” he says. “Before, we could fish all over the place … . Now it is not giving us enough income.”

Fishing could become even more challenging as this Persian Gulf nation of 1.8 million people prepares to build five new artificial islands containing five new cities by the end of the decade. Combined, the islands will increase the landmass of this tiny nation by 60 percent. While government officials say the addition of new real estate is central to Bahrain’s economic development, building the islands also carries significant environmental costs in a part of the world where marine life is already struggling to adapt to climate change and survive.

“The Persian Gulf as a whole is fairly stressed, as it is salty and hot. Any extra stresses on (the species that live there) usually have more harmful impacts that they might elsewhere,” says Charles Sheppard, professor of marine sciences at the University of Warwick, who spent seven years researching coral reefs in the region.

Island-building across the Persian Gulf

Reclaiming land from the sea, the term of art for creating new islands by dredging the seafloor, is a familiar process in Bahrain. The country underwent various coastal alterations in 1963, and has since expanded from 258 square miles to more than 300 square miles in 2021—making Bahrain today slightly larger in area than Singapore.

The small archipelago already comprises more than 30 natural and artificial islands. Muharraq, the northernmost city-island in Bahrain, has been slowly expanding since the 1960s and is now four times its original size due to reclamation.

Although Bahrain’s coastal changes are motivated by its size, island-building has been practiced among Bahrain’s larger coastal neighbors for decades, often on a grander scale. Some are especially striking, such as Dubai’s Palm Jumeirah, which started construction in 1990 as a group of offshore islands resembling a stylized palm tree that are home to luxury villas and hotels. Saudi Arabia is also building Oxagon, the world’s largest free-floating structure, set to be an 18-square-mile industrial hub. Other projects have been more conventional, such as Qatar’s New Doha International Airport, built on reclaimed land in 2006.

Bahrain’s proposed five new islands are part of an ambitious $30 billion plan to recover from the pandemic and help shift Bahrain from an economy built on oil to one driven by private businesses, manufacturing, and tourism. In 2020, the World Bank said Bahrain’s economy shrank by 5 percent, mainly due to sharp declines in oil demand during the pandemic. This year, the International Monetary Fund estimates growth of 3.3 percent.

“Bahrain is emerging from the pandemic with a bold ambition that looks beyond economic recovery to a more prosperous future,” said Sheikh Salman bin Khalifa Al Khalifa, minister of finance and national economy, at a briefing last November, where he described the blueprint for the government’s Economic Vision 2030.

Part of the $30 billion will fund 22 new development projects, including Bahrain’s first metro system and a new 15-mile causeway between Bahrain and Saudi Arabia.

More than doubling Bahrain’s land area is an ambitious task. The new islands are expected to add 180 square miles. The Bahrain Economic Development Board touts the five cities as sustainable; they are currently being designed to house an airport, luxury residences, and waterfront resorts, all while supposedly protecting natural habitats.

Environmental consequences of dredging

Scientists who have studied the history of the construction of artificial islands say there is reason to be concerned about the impacts of reclaiming land from the sea to build islands. Dredged material used to create reclaimed land often comes from shallow coastal waters, where seagrass beds provide food and protective nurseries for fish and other marine species, Sheppard says.

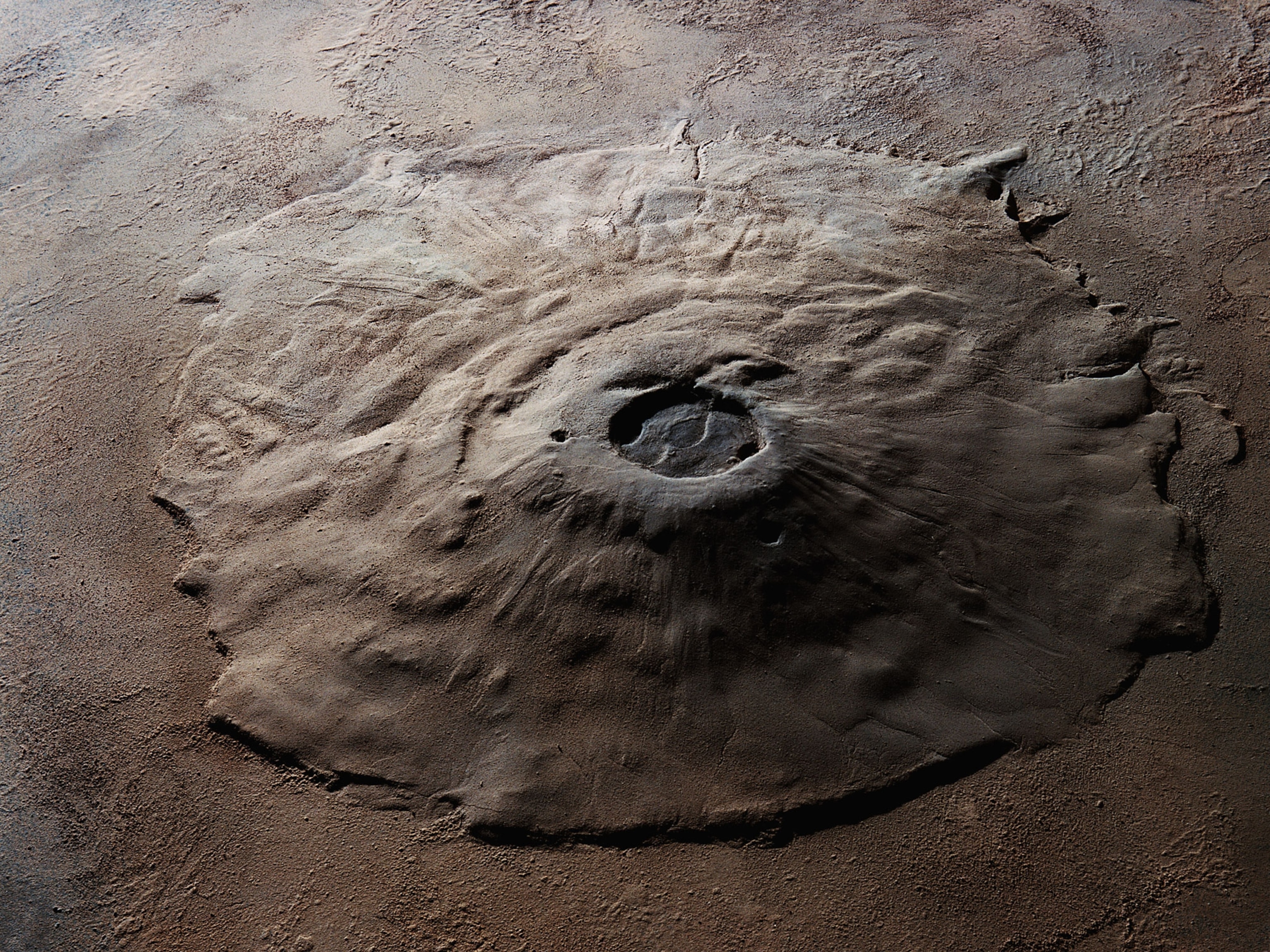

Of the five new islands, the two largest are planned to be built on and named after the largest coral reefs in the Persian Gulf, Fasht Al Adhm and Fasht Al Jarim. The reefs are shallow, hollow-domed reefs that extend more than 40 square miles each across the Gulf. They provide rich breeding grounds and vital marine habitats for hundreds of tropical species, including clownfish and stingrays. In 2000, a status of coral reefs across the Gulf published in the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network showed that years of sand dredging between 1985 and 1992 significantly damaged Fasht Al Adhm, the largest of the two.

“Imagine burying a cornfield under three meters of soil and concrete. It will die,” says Sheppard.

In Bahrain, the sand beds near Muharraq were used as popular dredging areas, resulting in 182,000 square meters of reef area being lost due to silt cover. Removing these sediments causes silt to flow directly onto the corals, “effectively burning and choking the coral polyps,” says Hameed Al Alawi, a Bahraini marine biologist and aquatic consultant.

Mohammad Shokri, a coral scientist who worked on the Gulf reef study and a marine biology professor at Shahid Beheshti University in Iran, says continued dredging efforts also can increase turbidity and sedimentation around the reefs, causing further stress.

“Efforts must focus on how to preserve what remains, as well as on active efforts on how to restore coral reef resources in the Gulf,” he says.

Environmental impacts aren’t limited to reefs. Scientists concluded in a paper published last May in Science Direct that dredging for reclamation projects between 1967 and 2020 contributed to the loss of 95 percent of the mangroves in Tubli Bay, off Bahrain’s northeast coast, where luxury seafront homes have been built.

Those changes translate into a significant loss in biodiversity and productivity, says Alawi. One environmental impact assessment conducted by the Bahrain Parliament and the Fishermen’s Protection Society (FPS) on land reclamation projects carried out between February 2008 and December 2009, showed a decrease in fish diversity from more than 400 species to less than 50.

“This means people will not notice until the damage is done,” says Alawi, estimating another 10 percent loss with the new islands.

Sheppard says reclamation projects in Bahrain and across the Gulf could have been managed differently, and used ecologically poor sites rather than ones rich with wildlife. “The sad thing is that much of the damage done could have been avoided,” he says. “There are several mitigation methods that could be used.”

The Ministry of Works, Department of Fisheries, and the Supreme Council for the Environment, the government agency that licenses and approves land reclamation projects, did not respond to multiple requests for comment. In a statement on the council’s website, officials said the council’s reclamation and dredging monitoring program aims to verify that projects are built following environmental protocols outlined in licensing, and that barriers are erected around site operations to prevent proliferation of turbidity.

Fish are migrating out to sea

For fishermen in Bahrain, the decline of fish stocks has pushed them further out to sea, sometimes into fatal conflicts with neighboring states. Over the past decade, roughly 650 Bahraini boats were detained by Qatari coastal patrols for encroaching in their waters, with two ships recently detained last April. Others resort to riskier methods, like using illegal fishing equipment such as nylon wire traps and actively ignore fishing bans.

“We understand that sand is like gold,” says Abdul Amir Al Mughani, director of the Fishermen’s Protection Society, which represents more than 500 fishermen. “But to us, reclamation is an attack on the sea.”

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- This fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then dieThis fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then die

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

Environment

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- How fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitionsHow fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitions

- Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

History & Culture

- Meet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'iMeet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'i

- Hawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowersHawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowers

- When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

Science

- Why ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevityWhy ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevity

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

- Should you be concerned about bird flu in your milk?Should you be concerned about bird flu in your milk?

Travel

- On this Croatian peninsula, traditions are securing locals' futuresOn this Croatian peninsula, traditions are securing locals' futures

- Are Italy's 'problem bears' a danger to travellers?Are Italy's 'problem bears' a danger to travellers?

- How to navigate Nantes’ arts and culture scene

- Paid Content

How to navigate Nantes’ arts and culture scene