Marichjhapi massacre: Forgotten story of Hindu refugees slaughtered in Bengal

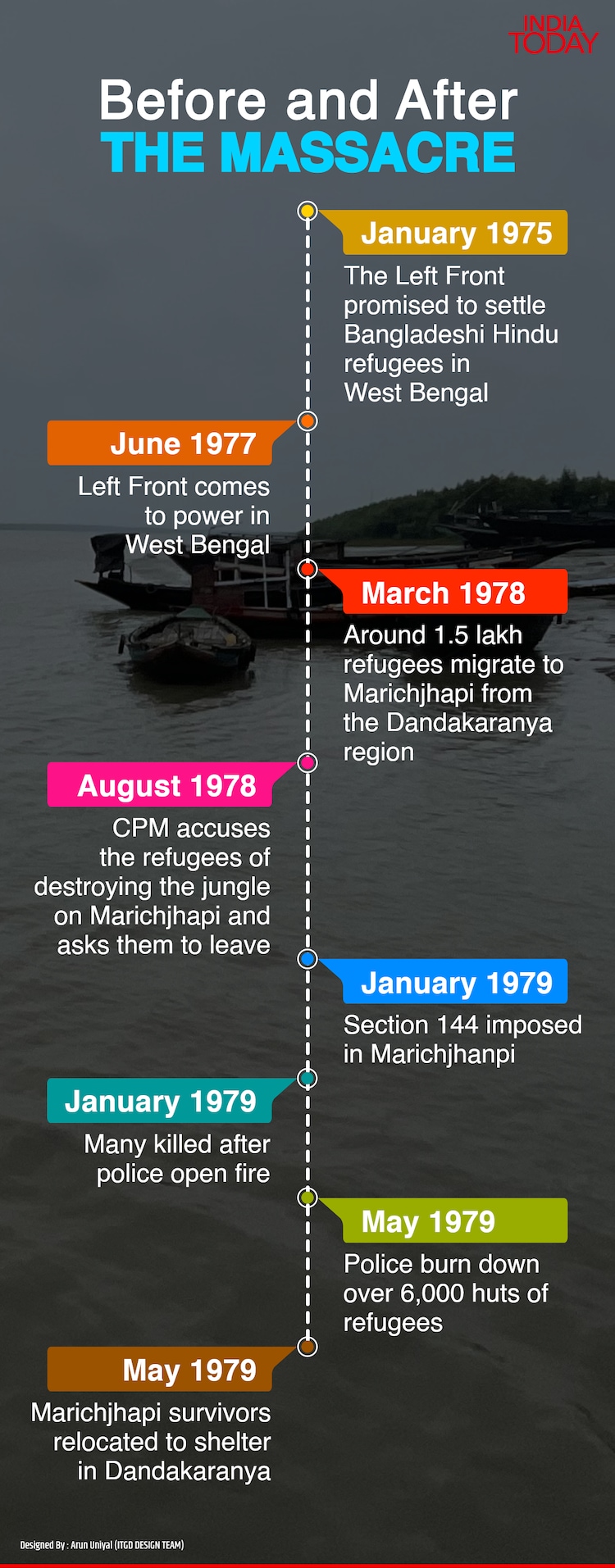

The chapter on the Marichjhapi massacre was torn from history books in such a way that no one even noticed it was missing. The story of thousands of Bengali Hindu refugees from Bangladesh being killed by the Left Front government in Bengal in 1979 is rarely discussed. This is how eyewitnesses recount the death and destruction.

The Sundarbans of West Bengal, known for its mangrove forests, marshes, venomous snakes and Royal Bengal tigers, has another face too. And it is a bloody one.

In 1979, a massacre took place on Marichjhapi, one of the over 100 islands of the Sunderbans. Thousands of Hindus who had migrated from Bangladesh were killed. Thousands disappeared. And so did the story that is soaked in blood and hatred.

West Bengal had a Left Front government then under Chief Minister Jyoti Basu.

But this chapter of death and destruction is now forgotten, except for a commemorative marble stone on the neighbouring island of Kumirmari, and in the scarred memories of the survivors.

The marble stone commemorating the massacre is blank, like most memories of the bloody events of 1979.

Marichjhapi is now a ghost island and Kumirmari is the nearest inhabited place. It takes about 20-25 minutes from Marichjhapi to Kumirmari on a motorized ferry boat.

A visit to Kumirmari, where some of the Marichjhapi survivors live, is essential for revisiting these scarred memories.

JOURNEY INTO SCARRED MEMORIES

The journey to Kumirmari is via Gadkhali Ghat in South 24 Parganas. During the almost three-hour journey on a wooden ferry, one gets to hear many stories of the surrounding areas, all wrapped in poverty and helplessness.

The islanders venture out on small wooden boats to catch fish, only to be taken away by tigers. Sometimes, crocodiles attack too.

Then, a lone person returns, steering the boat. Having witnessed a fatal tiger attack and blood-soaked bodies, he stays home for a couple of days, but then sets out again. ‘Both the lion and the man need food. Only one’s search is fulfilled,’ was the essence of the story.

The ground in Kumirmari is marshy and snake-infested.

Right after one steps off the ferry and takes a couple of dozen steps, one can see the white marble memorial recently erected in memory of the Marichjhapi massacre victims.

A small marble piece. Without a name or date, it is no different from any ordinary stone, except that it is the only marble among the makeshift houses on the impoverished island of Kumirmari.

Recently, the BJP, the main opposition party in West Bengal, started observing Marichjhapi Day.

On January 31 this year, people gathered in memory of the dead and the lost and lighted incense sticks in front of the stone. The air on the island was filled with noise and voices of justice for a few hours. Then it all went silent. An envelope of silence for the rest of the year.

REVISITING THE MARICHJHAPI HORROR

Panchanan Mandal, dressed in an oversized T-shirt and loose pyjamas, narrates his woes. “My wife is dying. She has a high fever. I’m poor and can't afford medicine or food. I can't comfort her. She will die. My wife will die.”

In a trembling voice, Mandal keeps repeating these words.

Panchanan Mandal, once a part of India, became a Pakistani after the Partition, and then a Bangladeshi after the 1971 war. And then, shifted to being an Indian again.

Despite his nationality changing multiple times, his misfortunes didn't end.

It seems it was a crime being a Dalit Hindu in Bangladesh. They were being driven out from there and somehow managed to reach India. But here too, the cycle of eviction didn't stop.

Panchanan Mandal starts limping back into memory lane and sharing his story. His story is the story of Marichjhapi – one of the found and lost.

In 1979, at the age of 18, Panchanan arrived at Marichjhapi, an island in the Sunderbans with dense jungle.

Over time, the settlers built a thriving community with a bustling population.

One day, the police ordered the inhabitants to vacate the island, but they refused. The police besieged Marichjhapi, cutting off all access to and from the island.

The islanders were self-sufficient in everything, barring fresh drinking water and grains which they had to fetch from nearby islands.

The siege led to their confinement in their own homes, with no access to clean water or food. Poison was mixed in the water of the only tubewell on the island.

Even as days passed, the police didn’t loosen their cordon of the island. People got desperate. Hungry and thirsty, they consumed contaminated and poisoned water, which resulted in dozens of deaths.

Eventually, some men attempted to breach the police cordon in small boats, which led to the police opening fire.

A chilling account emerges from the survivors of the massacre.

Panchanan Mandal says he and others were lured to a location with the promise of food. But it was bullets, not food, that greeted them.

“I got a place to hide amid the melee. From my hiding place I saw about 400-500 people being killed,” says Mandal.

He saw his family members and acquaintances falling dead to bullets right in front of his eyes. Some bodies were found floating in a river, others lay lifeless on the ground.

Now, he fears for the life of his ailing wife, the only one left from his family.

Another Kumirmari resident, Gopal Mandal, remembers everything as if it happened yesterday.

“We had built schools, hospitals and markets on Marichjhapi without any outsider’s help and this began bothering others,” he says.

“CPM leader Jyoti Basu was the Chief Minister of West Bengal then. He said, these people are destroying the forests, they need to be evicted from the island,” says Gopal Mandal.

“It was the day before Saraswati Puja, by 9:30 am, police surrounded us. Section 144 had been imposed. The island remained cordoned off for many days. Getting on it or getting off the island was impossible,” says Gopal Mandal.

One by one, the houses started running out of food grains.

“We went to the forest and started bringing whatever we found edible, including soft grass and new leaves. We would boil them and eat them. We survived on near-empty stomachs. There was no drinking water on the island. Whatever little there was, it was poisoned. People who were half dead on empty stomach started dying by drinking the poison-mixed water,” he says.

The islanders knew they wouldn’t be able to survive by remaining on the island without food and water. They got desperate and tried to sneak out on their boats.

That is when the police opened fire.

“I do not know how many fell to the police bullets. Big police launches were hitting and overturning the boats of the people trying to flee from Marichjhapi. Frightened, the people dived into crocodile-infested waters and died,” recounts Gopal Mandal.

Gopal has become an influential person on Kumirmari, but the anger of being uprooted thrice is reflected in everything he says.

The pain is the same across this island, the story is the same, he asserts.

Bijoy Bhai’s house is the closest to a brick house that is visible on the island of Kumarmari. He and his wife are too old to go out fishing or looking for crabs and survive on the money that their son sends from Chennai.

Bijoy shows a piece of paper – which is a Relief Eligibility Certificate and the names of four refugees are mentioned on it.

There were not four, but five people, says Bijoy. The fifth, his sister, died of hunger.

But how did the others survive? A cruel but pertinent question.

“We primarily lived on grass. At times, we used to pluck fruit from trees and throw it in front of animals. If they ate it, we used to scour the island for that fruit and lived on it for some time,” says Bijoy. “My sister was very young; she died pleading for rice and fish.”

But the trail of death didn’t stop with her. His parents fled Marichjhapi and reached Kumirmari, but didn’t live long.

Bijoy’s wife was born in Kumirmari itself. She keeps referring to their son, their only hope, who now has a job in Chennai.

Doesn’t he ever feel like going back to Bangladesh?

“Obviously I feel like visiting Bangladesh. I was born there. We had a proper house and agricultural land there. But if we could return, why would we be living here, despite all the assaults and the abuses that are heaped upon us?” asks the octogenarian Bijoy with a hollow smile.

CHRONICLING THE MARICHJHAPI MASSACRE

Journalist Deep Halder has written a book on Marichjhapi. His ‘Blood Island’ is an oral history of the people and forgotten figures of the Marichjhapi massacre.

“Although the Marichjhapi massacre took place in 1979, its story starts much earlier. After the Partition of India, Hindus started fleeing from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) to West Bengal. This continued for decades. West Bengal did not have the infrastructure to handle the flood of people pouring in. That is when the Dandakaranya project took shape,” says Halder.

People were being sent to Chhattisgarh (then part of Madhya Pradesh), Odisha and Andhra Pradesh.

When the refugees were leaving, the Left Front leaders promised that if they returned to power, they would bring the refugees back to West Bengal.

“After two years, the Jyoti Basu-led Left Front came to power, but now he had no intention of calling the people back,” says Halder.

The Hindu refugees, mostly farmers and fishermen, found themselves in an alien land. In inhospitable, landlocked terrain, they began to fall victim to mosquito-borne diseases. There was this urge to settle near their own people and home.

The Bengali refugees chose an island in the Sundarbans to resettle on. That was Marichjhapi.

“They started coming in thousands. It is said that around 1978, about 1.5 lakh people had made Marichjhapi their home, that too, without government help,” says Deep Halder, who interacted extensively with the former inhabitants of Marichjhapi for his book.

According to the journalist-author, this is how it built up to the Marichjhapi massacre.

The enraged Bengal government started saying that the refugees were damaging the forests. The pressure on the occupants to leave the island started increasing.

Ultimately, the government imposed an economic blockade on Marichjhapi. People were left without drinking water. Children and old people started dying.

“The refugees broke the police ring around the island and started fleeing, and then the police started firing at them. A lot of people were killed. This was the first chapter of the massacre,” says Halder.

Several attacks continued in the months that followed.

“Women were allegedly picked up from their homes in the middle of the night and raped so that there could be pressure on the refugees. But they still didn’t leave the island,” says Halder.

Finally, there was a serious attack in May.

Thousands of huts were set on fire. People who were trying to save their lives were packed onto a ship and sent to Kolkata and then to Dandakaranya. The forest region of Dandakaranya spans present-day Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Telangana, and Andhra Pradesh.

“There is no authentic record of how many people were killed, how many were left injured and how many went missing. People were killed and thrown into the river. It is said that the death toll could be up to 10,000. But the official figure stops at just two to eight,” says Halder.

LEFT FRONT POLITICS BEHIND MASSACRE

But why was the Left Front angry at the refugees?

Dalit activists in Gosaba of West Bengal believe that elite Bengali speakers were unable to live with the fact that refugees had settled and developed the uninhabited island with sheer hard work.

Gosaba is the point from where ferries are taken to the islands of the Sunderbans.

They say that the Left Front leaders sought votes promising to settle the refugees back in Bengal, but after coming to power, their intentions changed.

People of the Namasudra community (Dalits of Bengal) were returning to Bengal from other states where they had been packed off. They started settling on the island of Marichjhapi, not in the cities.

The Left Front, which had gone back on its promise, feared that a lot of votes could go against it in the next polls. To prevent this, it planned to drive away the people, activists say.

Soon, Marichjhapi was declared a protected area. It became easy to drive away people living there.

According to documents, in January 1979, then Bengal Chief Minister Jyoti Basu spoke to the Centre about concerns about refugees leaving the Dandakaranya camp and forcibly entering Bengal.

Soon after this, Section 144 was imposed.

Along with this, economic restrictions were put in force. This is the same restriction that economically powerful countries impose on enemy countries to cripple them. But all this was being done in our own country, against our own people.

On January 26, 1979, when the country was celebrating Republic Day, the people of the island were dying from lack of food and poisonous water as the island had been cut off by the police and no supplies could be brought from outside. Poison was mixed in a tubewell on the island, the only potable source of water there.

Dozens of people lost their lives drinking that water.

Seeing there was no escape, the islanders tried to flee from there in search of food and water. That’s exactly when the massacre started. Hungry and thirsty people trying to save their lives were shot and killed. It was January 31.

Women were raped to scare the islanders.

The barbaric act of the Left Front Bengal government has no precedent in Independent India, say activists.

The process of firing, rape and threats continued till May.

Finally, on May 18, 1979, then Information Minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharya announced that there were no more refugees in Marichjhapi.

Massacre survivor Gopal Mandal says the tigers of the Sunderbans turned into man-eaters after feeding on the half-dead people of Marichjhapi. That was the time, says Mandal, when dawn would break not to the sweet chorus of birds but to the heart-rending screams of people.

There is really nothing in Marichjhapi now. It is indeed a ghost island. Only that it would be difficult to bury the ghosts of its past.