The Dalit awakening

The outpouring of Dalit rage in the Hindi heartland underscores their new assertiveness. what impact will it have on national politics in the run-up to 2019?

It began like any other summer morning across northern India. But as the heat of the day built up on April 2, regular commuters were checking if anyone had heard of a Bharat Bandh called by little-known Dalit groups. They were apparently protesting a Supreme Court ruling from almost two weeks earlier, which had diluted the stringent provisions in the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989. By noon, though, most of India knew about the Bharat Bandh as TV screens started flashing images of street violence in 10 states, as groups of seemingly leaderless Dalits clashed with police or upper-caste gangs. At the end of it, 11 people were dead and property worth crores destroyed. It was not just the state administration that had been caught unawares; the spontaneity of the protests had even made the opposition parties sit up and take note.

The court ruling was only the trigger, but what India witnessed on April 2 was an explosion of pent-up resentment, a sort of climax to a steady build-up of mistrust between Dalits and upper castes in various parts of the country, a violent manifestation of fear that the entire "system" was conspiring to pull them down again, and strip them of their constitutional rights. Indeed, on the day, many protesters were even heard saying they were revolting against the "scrapping of the reservation system" in the country. For Dalits, the moment was now or never.

"As a Dalit sociologist, I can argue that this is the accumulated anger of a group that has been humiliated and stigmatised for ages," says Vivek Kumar, professor of sociology at the Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi. The social and economic policies of the Narendra Modi-led central government have not helped matters. Demonetisation and the violence by cow vigilantes have hit the marginalised Dalit community the hardest.

BJP Dalit MP Udit Raj says there were multiple catalysts for the violent incidents of April 2. "Before this judgment, there was another one on SC/ ST/ OBC recruitment in colleges, which diluted the reservation criteria. Meanwhile, there is hardly any recruitment in government jobs and that has frustrated the Dalit youth. The contract system, privatisation and disinvestment did their bit to make reservation norms inconsequential. And then you have incidents like the Rohith Vemula suicide and the atrocities in Una, Saharanpur, Koregaon. They have all contributed to the tipping point we see now," he says.

As Kumar explains it, the April uprising also signifies that the Dalits have now rejected the patronising 'mai-baap' culture of political parties-they don't need them to espouse their cause. An increasing awareness about their electoral power coupled with a rise in literacy and a measure of economic liberation have emboldened Dalits to assert their social and political rights. Instead of political parties setting the terms of engagement, Dalits now are setting the agenda for politicians. The message rings out in the powerful voice of teenaged Dalit singer from Punjab, Ginni Mahi, and her take-no-prisoners hit, Danger Chamar. As the 2018 summer sets in, the rest of India may sit up and notice the new mood of Dalit self-assertion.

Perhaps the Supreme Court underestimated the likely reaction on March 20 when it struck down several stringent provisions in the SC/ ST Atrocities Act. Noting that there were "instances of abuse" by "vested interests" for political or personal reasons, the top court laid down multiple safeguards, including provisions for anticipatory bail and a "preliminary inquiry" before registering a case. It also said a public servant could be arrested only after written approval from the appointing authority, while for an ordinary citizen a written approval from a senior police officer (SSP) was needed. Ironically, the top court issued the order with the stated objective of "creating a casteless society".

The bench of Justices A.K. Goel and U.U. Lalit had decreed that any law should not result in caste hatred while expressing its anxiety over misuse of the Atrocities Act. It was hearing a petition filed by Subhash Kashinath Mahajan, director of technical education, Maharashtra, against a Bombay High Court order. The HC had rejected Mahajan's plea challenging an FIR against him for denying sanction to prosecute an official of the department, who had made adverse remarks in an employee's annual confidential report.

Though it was a court ruling, the BJP, the party in power at the Centre and in 20 states, had to bear the brunt of the Dalit anger. To be fair, the Union government did oppose the dilution of the act in the course of the hearing. Admitting that there has been misuse of the law, additional solicitor general Maninder Singh said the issue-making provisions for punishment in case of false complaints-was examined by Parliament but the government took the stand that punishment to SC/ ST members would be against the spirit of the act. He also contended that the court should refrain from issuing guidelines on the issue and that it was for the legislature to take a call.

Union minister for social justice and empowerment Thawar Chand Gehlot argues that the Narendra Modi government, contrary to popular perception, has even tightened a few provisions of the existing act. For instance, crimes like preventing a Dalit from riding a horse at a wedding procession or tonsuring his/ her head was made punishable three years ago. However, there was no satisfactory explanation from the government on why it took nearly two weeks to file a petition in the Supreme Court seeking a review of the judgment.

The apex court, meanwhile, has refused to put its ruling in abeyance, saying its March 20 order was only meant to safeguard innocent people without affecting the rights of the marginalised communities. It will, however, consider the arguments against its judgment from all parties involved at the next hearing scheduled sometime in mid-April.

HAS THE LAW BEEN MISUSED?

The complaint that the Scheduled Castes can misuse the act to blackmail upper caste individuals is not new. Tamil Nadu's Pattali Makkal Katchi, a political party dominated by upper caste Vanniyars, has been asking for the law to be repealed for several years.

Last year, when huge crowds of the Maratha caste held protests across Maharashtra asking for reservations for their community, one of their demands was for the dilution of the atrocities act, on the grounds that too many false cases were being lodged against Marathas. In response, the Maharashtra Police submitted a report to the state government stating that there was no clear evidence to indicate the act was being misused. "No doubt there has been misuse of many acts and this is one of them. Why didn't the Supreme Court take a call on other acts? The court has altered the basic structure of the Prevention of Atrocities Act by involving a third party," says Udit Raj.

While delivering the verdict, the apex court had referred to data submitted by the National Crime Records Bureau to highlight the misuse. The court said almost 15-16 per cent of the total complaints filed in 2015 under the act were false, and out of the cases disposed by the courts that year, 75 per cent had resulted in acquittal/ withdrawal.

The low conviction rate has often been presented as a supporting argument for dilution of the stringent provisions of the law. A 2015 investigation by the Media Institute for National Development (MIND) Trust in Tamil Nadu found that 30 per cent of prevention of atrocities cases were closed due to "mistake of facts", highlighting the discretion available to the police. "Instead of misuse, this law has in fact not been used to its potential. This is evident from the high rate of acquittals. For instance, in Rajasthan's Bhanwari Devi case in 1992, the court absolved her upper caste rapists saying the boys would not do such an act in front of their father," says Kumar.

Other Dalit scholars too agree that the argument that the law has been misused is highly exaggerated. "The social background of the victims is different from the officials who operate with their own preconceived notions and prejudices against the Dalits. The victims are also, in all probability, subordinate to the perpetrator. Registering a complaint becomes difficult with little social capital to rely on. There are different kinds of pressure to withdraw the case. So often the acquittal is not because of an 'absence of crime' but because of the lack of social position required to fight the case," says Prof. Sanghmitra Sheel Acharya, director of the New Delhi-based Indian Institute of Dalit Studies (IIDS).

According to Nandini Sundar, professor of sociology at the Delhi School of Economics, the number of cases filed under the act does not at all reflect the actual number of atrocities, as the "police often don't file FIRs". "The act is ultimately as good as the police and judiciary, and both are systematically biased against the SC/ST," she says.

DALIT BALLOT POWER

Dalits have huge electoral significance, and with four big states going to the polls this year and a Lok Sabha election slated for early next year, no party wants to miss out on this constituency. The electoral success of the BJP in the 2014 elections is a clear lesson-the party's Dalit vote share doubled to 24 per cent from 12 per cent in 2009. Of the total 84 Lok Sabha seats reserved for SCs, the BJP won 40, including all 17 in UP.

According to the Delhi-based Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), 85 per cent of Dalits across the country voted for the BSP at the peak of its popularity in the early 2000s. In the 2012 UP elections, Dalit support for the BSP went down by 23 percentage points, resulting in a massive victory for the Samajwadi Party. And in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, Jatav (Mayawati's caste) support for the BSP dropped by 16 percentage points and other Dalit support by 35 percentage points, resulting in the party getting zero seats.

An analysis of assembly election results where non-BJP, non-Congress parties have won further demonstrates the significance of Dalit votes. For instance, the Trinamool Congress in West Bengal, the Biju Janata Dal in Odisha and the AIADMK in Tamil Nadu all garnered a major segment of the Dalit vote in their states. In Telangana, the Congress lost a substantial share of Dalit votes to the Telangana Rashtra Samithi, which easily formed the government.

If Dalit votes played a key role in BJP's electoral successes, they were also behind its poor performance in Bihar and Delhi. Many BJP insiders agree that RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat's appeal for a review of the reservation system just before the Bihar assembly polls spelt doom for the party's prospects in the state.

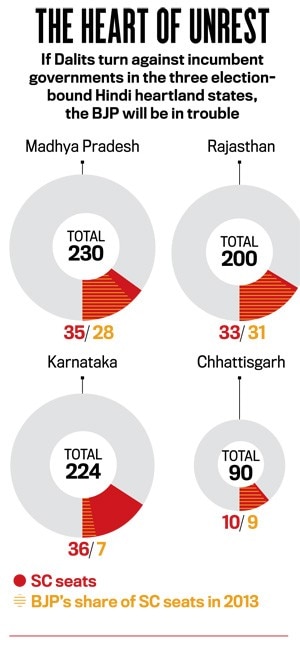

Now, given the apparent rise of attacks on Dalits and the growing outrage in the community over the court ruling, opposition parties sniff an opportunity to snatch back the Dalit vote bank from the BJP. The immediate battleground will be the four big states going to polls later this year-Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh-which account for 19 per cent of the country's Dalit population.

"Under normal circumstances, the Dalits don't vote together," says sociologist Dipankar Gupta. "But when there is an issue affecting them, it has a pan-India appeal. What happens to Dalits in Gujarat will certainly impact Dalits in UP or Bihar. Naturally, all political parties are trying to milk the issue as it will consolidate Dalit votes."

THE COUNTER ATTACK

Meanwhile, the upper caste reaction has already begun. Just a day after the Dalit protests, fresh violence broke out in Rajasthan as a 5,000-strong mob in the town of Hindaun set ablaze the houses of a sitting and a former MLA, both Dalits.

Dalits have been killed for growing a moustache, marrying beyond their caste, riding a horse and all kinds of activities that are perceived as defiance of the existing social order. While the apex court verdict could be the catalyst, the discontent has been simmering for quite some time as was seen in the suicide of Dalit PhD scholar Rohith Vemula in January 2016. It triggered a series of protests in campuses across the country against institutionalised caste discrimination.

In July 2016, the brutal thrashing of four Dalit youths in Una, Gujarat, by cow vigilantes, led to widespread protests across the country and from these protests emerged a new Dalit leader, Jignesh Mevani, who is now an MLA in Gujarat. In May 2017, Chandrashekhar Azad, leader of a new and popular Dalit organisation, the Bhim Sena, was arrested for allegedly spearheading violence in Saharanpur, UP, where Dalits clashed with the police. A day after he was granted bail, with the HC saying cases against him were "politically motivated", the UP government charged him under the stringent National Security Act. He continues to languish in jail.

In January, a Dalit celebration at Bhima-Koregaon village in Pune to mark the 200th anniversary years of a battle between the British Army's Mahar (a Dalit caste) regiment and the Peshwa's Maratha army led to widespread violence in Maharashtra with over 300 people detained in Mumbai alone and the government suffering losses to the tune of Rs 700 crore. Some groups saw the Bhima-Koregaon function as an assertion of Dalit identity.

In fact, for most of 2017, Maharashtra was consumed in clashes between Marathas and Dalits. But on April 2, the state's Dalits were cold to the countrywide strike. This was because, for one, no major political party called for protests and, two, the Dalits had already taken out a huge march in Mumbai on March 26 demanding the arrest of Hindutva icon Sambhaji Bhide for instigating attacks on the community in Koregaon-Bhima on January 1. Another big protest within such a short span of time would have been difficult to muster.

According to Prakash Ambedkar, a prominent Maharashtrian Dalit leader, the community was not too aware about the protest. "It wasn't coordinated," he says. "Messages were circulated on social media and in Hindi. They did not reach the non-Hindi belt."

BJP CAUGHT IN A TRAP

While the recent court ruling has put the BJP in a spot, several of its leaders have also contributed to the Dalit suspicions about the party's agenda. On March 30, BJP president Amit Shah was heckled in Mysuru over anti-Dalit remarks made by Union minister Ananth Kumar Hegde in January. Shah sought to pacify the Dalit leaders by distancing the party from Hegde's remarks (he had allegedly compared Dalits to dogs) but it still rankles with the community.

The minister too had apologised but he has made a habit of courting controversy of late. In December 2017, Hegde had said that the BJP would change the Constitution of India. This did not go down well with the Dalits either. "For the last four years, there has been talk about amending or doing away with the Constitution. The Dalit community sees this as an attack on the revered Babasaheb Ambedkar. The SC ruling too has been perceived as a way to test the waters before the Constitution is amended," says Anil Sirvaiyya, vice-president of the Dalit Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (DICCI).

In 2016, BJP leader Dayashankar Singh caused a stir by suggesting that India's most prominent Dalit leader BSP chief Mayawati's character was "worse than a prostitute's". "The BJP is blatant about not being ready to share power with the Dalits. Dalits are given shampoo and soap to bathe before they go to meet Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath. Now, even Ambedkar is not being spared," says Prof. Kumar.

Dalit intellectuals also point to how the UP government is trying to usurp Ambedkar-a Buddhist-as a Hindu icon, by highlighting his father's name, Ramji. On March 28, 2018, the Yogi Adityanath government decided to introduce Ambedkar's middle name 'Ramji' in all references to him in the state's official correspondence and records. Ambedkar's grandson Prakash Ambedkar has openly questioned the move. "By highlighting his middle name 'Ramji', the BJP government obviously wants to link Babasaheb to the Ram temple," he says.

The appropriation of Ambedkar as a Hindu icon is also seen as a ploy to not only counter the opposition plan to split the Hindu votes, the consolidation of which swept the BJP to power in 2014 and in several subsequent assembly polls, but also to stop a probable alliance between Dalit and Muslims. The BJP-RSS clamour for a beef ban and incidents of lynching are helping the opposition redraw the Muslim-Dalit nexus. The combination paid dividends for Asaduddin Owaisi's All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM) in Maharashtra in 2015. The party put up an impressive show in the Aurangabad corporation election, jumping to the No. 2 spot ahead of the BJP and behind the Shiv Sena, winning 25 seats in the 113-seat corporation. Among the successful AIMIM candidates were four Dalits and a Hindu OBC. The BJP certainly doesn't want such an experiment to spread to the national level.

DAMAGE CONTROL

Despite the occasional missteps, electoral compulsions have also driven the BJP to court Dalits with a number of outreach programmes. Unwilling to lose the support base that has served the party so well since 2014, it has been trying very hard-from celebrating birth anniversaries of Dalit icons to tom-tomming the selection of Ram Nath Kovind, a Dalit, as the country's president.

It has already taken a sharp U-turn on Ambedkar over the last decade-from the time of Arun Shourie, a senior minister in the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government, calling him a "false god" to the series of programmes launched by the Modi government to celebrate his contribution to the social and political fabric of India. Even the RSS mouthpiece Organiser now hails him as the "ultimate unifier".

The RSS, in fact, has coined the slogan 'One well, one temple, one crematorium' to take a position against discrimination in villages. Manmohan Vaidya, the new RSS national joint general secretary, calls this "the most powerful programme of Dalit inclusion in the country" but laments that "the country's ugly brand of politics still comes in the way of Dalit empowerment".

The Union government claims an impressive number of beneficiaries of the Modi government's welfare schemes such as Mudra, Jan Dhan, Ujjwala and rural housing are Dalits. Under Mudra, a total of Rs 4.73 lakh crore of loans have reportedly been disbursed to over 106 million people, of which 15 per cent are Dalits. In the Ujjwala scheme, 30 per cent of the total 40 million beneficiaries are Dalits. In Jan Dhan, 20 per cent of the total 310 million account holders are Dalits. In the PM's rural housing scheme, some 28 per cent of the 4.6 million beneficiaries so far are Dalits.

On April 5, 2016, Modi announced the Stand-up India scheme under which 15,000 Dalit entrepreneurs have been given loans, ranging from Rs 10 lakh to one crore. A special venture capital fund of Rs 250 crore has been allocated to 70 leading Dalit entrepreneurs. The central government PSUs have given about 2,000 Dalit entrepreneurs business worth Rs 373 crore in three years. "No government has done as much to empower the Dalits as the Modi government is doing now," says Milind Kamble, president of the Dalit India Chamber of Commerce and Industry. BJP MP Udit Raj, though, is unconvinced. "Schemes like Stand Up India, Mudra Loan etc are well intentioned, but many Dalits and tribals are yet to get their benefits. A government job is a lifeline for Dalits, and these are hard to come by now. The issue hasn't been addressed," he says. He feels there is a big communication gap between the BJP's top Dalit leaders and the community.

The aggressive Dalit outreach has also created a Catch-22 situation for the ruling party. In 2017, the Madhya Pradesh government had announced a scheme for training of Dalits as priests but withdrew it after protests from upper castes, especially Brahmins, who form the BJP's core vote bank.

One of the Modi cabinet's most prominent Dalit faces, Ramdas Athawale, has also come down heavily on the government for not making public the caste census data from the Census Report 2011. The NDA government is yet to make it public even as it released the data on rural and urban socioeconomic indicators more than two years ago.

DALIT STRUGGLE CONTINUES

It's not just the caste data: what gets hidden in the political slugfest over Ambedkar's legacy and the court ruling is the ground realities of the socioeconomic conditions of the Dalits in the country. The ability of Dalits to influence electoral fortunes as a political unit, especially in states such as UP, Punjab, Bihar and MP, has ensured that every political party routinely professes its love for them. But the abyss between lip service and the socioeconomic reality of India has fuelled a social conflict that has now reached a flashpoint. As Udit Raj puts it, today a crime is committed against Dalits every 15 minutes in India. And six Dalit women are raped every day. Between 2007 and 2017, crimes against Dalits saw a 66 per cent hike.

Gupta sees this phenomenon as a consequence of the growing resentment among upper castes about sharing social and political privileges with Dalits. "When oppressed classes start asserting themselves, backlashes happen. In the US, the lynching of Blacks started in the latter part of the 19th century when they began asserting their rights. The same is happening with the Dalits," he says,

Not that Dalit atrocities have risen only under BJP dispensations. For instance, UP saw a 25 per cent rise in crimes against Dalits between 2015 and 2016-the highest in the country-as against a national average of 5 per cent during the same period, according to a recent National Crime Research Bureau report. The SP ruled the state during that period. At the same time, several BJP-ruled states such as MP, Haryana and Gujarat also showed a sharp rise in crimes against SCs. Prof. Sundar attributes the rise to a combination of three factors-an atmosphere of impunity due to Hindutva politics, a resurgence of upper caste hegemony and increased Dalit assertion.

Seven decades after Independence, more than three-fourths of India's SCs still live in rural areas and 84 per cent of them have an average monthly income of less than Rs 5,000. And it's not just a rural phenomenon. According to Prof. Acharya, an IIDS study on rental housing in the NCR in 2012 showed evident prejudice in offering rental accommodation to SCs. "The bias was also evident in hirings in private firms in urban areas. Many more applicants from upper caste backgrounds were called for interview compared to SCs and Muslims despite all other characteristics-educational and social-being similar," she says.

The 2011 Census data shows that more than 60 per cent Dalits do not participate in any economic activity. Of the working population, nearly 55 per cent are cultivators and agricultural labourers. Around 45 per cent of rural SC households are landless. Only 13.9 per cent Dalit households have access to piped water, only 10 per cent access to sanitation compared to 27 per cent non-Dalit households. A staggering 53.6 per cent Dalit children are malnourished.

Some argue that the current assertion of Dalits reflects the aspirations of the post-liberalised economy. "The number of educated Dalit youth has grown exponentially after the 1991 economic liberalisation," says K. Raju, head of the Congress's SC cell. "However, jobs and opportunities in government sectors have shrunk. And they still do not have significant access to the private sector. These disillusioned Dalits are looking for a change." Certainly the dilution of the Atrocities Act was not the change they were looking for. n

With Uday Mahurkar, Rahul Noronha, Amitabh Srivastava and Kiran D. Tare