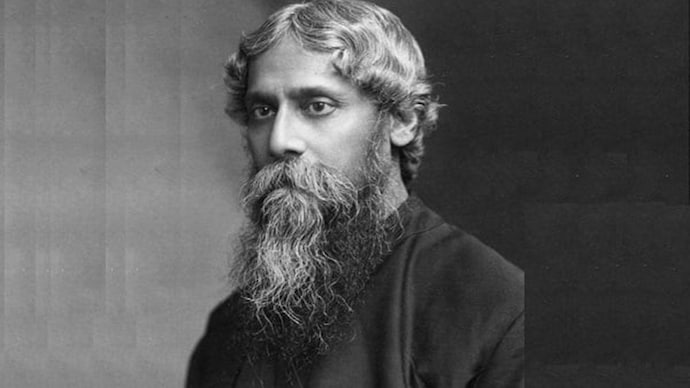

From the India Today archives (1983) | Rabindranath Tagore and the Nobel riddle

As the nation celebrates Tagore’s 162 birth anniversary, a look at the controversy that had dogged the literary icon’s Nobel Prize

(The article was published in the INDIA TODAY edition dated October 31, 1983)

(The article was published in the INDIA TODAY edition dated October 31, 1983)

"I used to be 5 feet 9 inches tall but I seem to have shrunk—the burdens of the Nobel Prize." —Saul Bellow, Nobel Prize-winning novelist, 1976

Nobody shrank more under the burden of the Nobel Prize than Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), the best-known Indian man of letters till now, and the first Bengali author whose fame transcended national frontiers. The Swedish Royal Academy's decision to confer the Nobel Prize for literature on Tagore in November 1913, almost overnight chilled his relations with a band of his admirers in England—W.B. Yeats, Ezra Pound, Robert Bridges, the poet laureate of the time; and William Rothenstein, the artist. Pound accused him of manipulation; Yeats a personal friend who had written a 22-page preface to the first edition of Gitanjali (Song Offerings), refrained from congratulating him; Rothenstein turned diplomatic; and Bridges, in a letter to Tagore, called the prize a "crown of bank notes".

But that was 70 years ago. At the moment, Calcutta, Tagore's home town, is warmed up not to the thought of one of its citizens past glory, but with new doubts about the circumstances in which he got the prize. This time around, the doubting Thomas is a 45-year-old bearded Marxist researcher and essayist, Nityapriya Ghosh, whose two earlier books on Tagore are critical of him both from nationalist and socialist standpoints. Nityapriya Ghosh has suggested that the Nobel Prize academy's decision was prompted not by Tagore's reputation but by royal prodding from Prince William, the Swedish crown prince Recently, Ghosh dealt another sledgehammer blow to Bengal's hallowed edifice of Tagore-worship in a 5,000-word article published in the Ananda Bazar Patrika, called "The Mystery of the Nobel Prize", he suggested that the academy's decision was prompted not by Tagore's reputation in England but by "hidden Royal prodding" from Prince William, the crown prince in Sweden's ruling house of Bernadotte. In 1913, the Swedish royalty was smarting under the insult of Norway's secession in 1905 and - argues Ghosh - would have gone to any length to spite the British, including conferring the Nobel on a member of their subject race, because the Norwegians had chosen for their king and queen a son-in-law and a daughter of King Edward VII.

The iconoclast: Ghosh has expanded the theme further in an article in the annual number of Prama, a socio-cultural research magazine due for publication this fortnight, where he has argued that Tagore—till 1912 a firm non-believer in the worth of finding an international audience—got interested in getting his works translated into English largely because Prince William had dangled the carrot of the Nobel Prize before him. His article is in the form of an extended hypothesis; but it violently clashes with accepted ideas such as:

- The Swedish Royal Academy awarded Tagore with the Nobel Prize because his poetry, bordering on the mystic and set in a style altogether different from the pre-First World War European verse, had already taken England by storm;

- The prize came to Tagore as an unexpected, and unsolicited gain, and certainly nobody had ever lobbied for it;

- The academy had fully considered the merit of Tagore's poetry before deciding to honour him;

- And that politics played no part in influencing the academy's decision.

Ghosh's persuasively argued theory casts a sceptical look at each of these assertions, and subtly corroborates a parallel undercurrent of Bengali doubt about Tagore's greatness. The doubt is almost as old as the present century and has recurred at periodic intervals, being expressed by all sorts of people: Tagore's orthodox Hindu critics; his contemporary 'purists'; the custodians of morality in literature; the avant garde naturalist writers of the '30s; the Marxists. Over the years, these charges have been subjected to the law of diminishing returns. What Ghosh has now done is to steer clear of any judgement of Tagore's poetry, but to hint that the Nobel Prize was a royal bounty, and that Tagore was "not unaware of the campaign in Stockholm.

Angry reaction: But Ghosh's theory has naturally raised the hackles of the powerful Tagore establishment in West Bengal. Besieged with a volley of critical letters, some of them downright unprintable, the Ananda Bazar Patrika closed correspondence on the subject after carrying a dozen of them in its letters columns. The strongest was from Somendranath Bose, director of the non-official Tagore Research Institute, a highly respected study centre that awards diplomas after two years of Tagore study. Bose told INDIA TODAY: "There is not an iota of extra evidence, which is not published so far, that Nityapriya Ghosh has brought up in support of his rather warped theory. He is merely trying to sensationalise the issue." Said Maitreyee Devi, author of several books on Tagore and his associate for 15 years: "I am confident that Prince William did not lobby for Tagore. The tide of Tagore's popularity in Britain reached Sweden and compelled the Swedes to award him the prize. Nityapriya should immediately stop his delirious outpourings." Observed Ujjwal Kumar Majumdar, reader in the Bengali department of Calcutta University and the author of an important book on Tagore: "It is a useless controversy. Even if some royal personage had pulled strings for the award, it does not take away from the merit of Tagore's poems."

But is the controversy really "useless"? Perhaps not. A large number of young Tagore scholars in Calcutta as well as at Santiniketan, the university town associated with the memory of Tagore, 150 kilometres from the city, feel that Tagore's cultural conquest in the West has not been adequately explained, and that there is a persistent mystery about the Nobel Prize.

Tagore won the prize at the age of 52, a month after he had returned home from a 17-month trip to Europe and the United States. The prize, worth Rs 120,000 at that time, was announced on November 13, 1913. Till then, the English translations of Tagore's works that had been published were: Song Offerings (India Society edition-November 1912; Macmillan-March 1913); The Gardener (Macmillan-October 1913); The Crescent Moon (Macmillan-October 1913); Sadhana (Macmillan-October 1913); and Glimpses of Bengal Life (G.A. Natesan-Madras, October 1913). While handing over the prize, Harold Hjarne, president of the academy's Nobel committee, mentioned all the five books. It was December 10, 1913.

The prize is awarded by a committee of 18 academy members, four of whom form a special board. The committee invites nominations from various national academies (such as the Royal Academy of Literature in England); even past Nobel laureates are entitled to recommend names. The nominations come in till the last day of January: on February 1, the four-man board screens the nominations and circulates copies of the works of the short-listed authors among the 18 committee members. The members scan the works between February and October, and meet twice after October 1, to discuss among themselves and then to elect the winner.

Till February 1, only Song Offerings had appeared in print. So, the inevitable question is: did the committee take its decision on the basis of just one volume of 103 poems, emended liberally by Yeats in the version translated by Tagore from the original Bengali? Conversely, the committee had to disregard the claims of 27 other nominees, including Anatole France (1844-1920), the French satirist, novelist and critic, and Thomas Hardy (1840-1920), the British novelist and poet, to confer the prize on Tagore. Ironically, Tagore was not even an official nominee that year. The Royal Academy of Literature, of which even Yeats was a member, had suggested the name of Hardy: it was only R. Sturge Moore, a fellow member and a minor poet forgotten by now, who had put up a brief note before the committee suggesting Tagore's name. Moore's five-line letter did not mention a single book by Tagore.

Ultra orthodoxy: The 18-member committee met on October 29, 1913, to discuss the nominations they had received. Hardy got unceremoniously disqualified on the ground that his literature was "pessimistic" in its content, a trait which Alfred Nobel, the donor of the prize, had run down in his will. Similarly, France was considered a "sceptic" and had to wait for nine years to be qualified for the prize. This was neither shocking nor inexplicable: the Nobel committee's orthodoxy and bias were earlier manifest when it denied the prize to Tolstoy (1902 and 1903), August Strindberg, the playwright (1906), and Joseph Conrad, the novelist (1907), on grounds varying from preaching anarchism to drunkenness and bohemian conduct.

But why was Tagore chosen? In England and America, the poet had by then become a literary celebrity, but the Nobel committee was only vaguely aware of it. One of its key members, the poet Verner Heidenstam, who got the prize himself in 1916, said at the meeting: "For the first and probably the last time for a number of years to come, the privilege has been granted to us to discover a great name before it has had time to be paraded for years up and down the columns of daily newspapers." Hjarne himself said: "The prize awarders considered that there was no great cause for hesitation... on the ground of the poet's name being still comparatively unknown in Europe". Per Halstrom another member in his report, mentioned that he had "just seen" three British newspaper reports on Tagore's poetry and had read both Song Offerings and The Gardener.

Inconsistent claims: Even on this insufficient evidence, an unflappable Halstrom, in his report, said: "...no poet in Europe since the death of Goethe in 1832 can rival Tagore...." Hjarne wrote a letter to Macmillan and Company as late as December 14, 1913—a month after the prize had been announced - in which he requested the publishers to send copies of all Tagore publications in Bengali as well as English. Wrote Hjarne: "Of course we are acquainted with his principal works in English translations (and to some extent of his Bengali books also...)."

The question is: on the basis of only Song Offerings and The Gardener, three newspaper clippings, and a five-line recommendation from an individual member of the Royal Academy of Literature, how did the Nobel committee jump to the conclusion that it had indeed stumbled on a person who could succeed Goethe? Alternatively, if it had gone by his Bengali work, some 75 titles (out of a total of 180) of which had appeared by then, who had provided them with the basic information? If the "tide" of his popularity in England - as Maitreyee Devi put it - had not reached Sweden (obviously it didn't: Heidenstam was "discovering a great name"), who briefed the committee on Tagore's potential greatness?

Mysterious benefactor: The trail indeed becomes murky after this. Ghosh asserts that Tagore's unnamed benefactor was none other than Prince William who visited the Tagore's ancestral house at Jorasanko in Calcutta in the summer of 1912. The Tagores were a showpiece in Bengal of that time. Ghosh's assumption is based on William's travelogue, Wo die Sonne scheint (Where the Sun shines), where he writes of the Tagores: "Now and then... contemporary India was mentioned in our conversation. And then it always seemed as though a painfully repressed fire began burning in the heart of the brothers. Their eyes were glowing, and they spoke of hatred, hatred against Englishmen". Truth, a contemporary London magazine, confirms the Tagores' princely connection. In its issue dated December 24, 1913, a copy of which is kept at the Santiniketan archives, its Paris correspondent writes: "Prince William's visit to Calcutta, Swedes have said, brought about the award of the Nobel Prize to Rabindranath Tagore. This Bengalee poet in the opinion of French and other orientalist scholars, is hardly a typical oriental, but rather an Anglo-Indian hybrid..."

William was obviously charmed by the grand reception accorded to him at the Tagores'. Truth writes: "An appointment was made in the evening... cushions, encased in blue silk, lay piled on a matted floor. Ancient vases in bronze and other metals stood here and there, fascinating the eye .... servants with silent step brought in tea and cigarettes. Prince William lay down to smoke and follow the conversation." But William was also taken in by the Tagores' "....hatred, hatred against Englishmen". Ghosh slyly says: "The rest is history". He argues that "all the hype" in Hjarne's address, the comparison with Goethe, "can be explained in terms of the princely prodding".

Significantly, the Tagore-idolatry in the Anglo-Saxon West ended with the award of the Nobel Prize. The Who's Who of 1913, published by the British Government, did not as much as mention Tagore. The Cambridge History of English Literature, Vol. 14, published in 1916, was silent on him in its chapter on "Anglo-Indian Literature". Yeats, in a letter written to Rothenstein in 1935, piquantly observed "Damn Tagore.... Tagore does not know English, no Indian knows English". As early as 1917, Yeats was claiming - and not altogether unjustifiably - that he was responsible for "continual revision of vocabulary and even more of cadence" of Song Offerings and The Gardener.

Disillusionment: Probably, in its first fine careless rapture, the West took Tagore for a "mystic", a "messenger" and "prophet", rather than a strictly literary figure. With the war casting its shadow over Europe, the image worked, up to a point. Despite friendly warnings, Tagore mistook the adulation for genuine appreciation of his work, and came up with the rather weird theory that there were two kinds of Englishmen - the "little" and the "big". But the big turned mean before long, and a disillusioned Tagore turned more and more to the anti-British formations in Europe, including Fascist Italy.

But unfortunately for Tagore, the Nobel Prize episode presented him in Britain as a literary climber and caused his "mystic" image to wear off. The sale of his books in England and America, instead of shooting up after the Nobel, hit a longish plateau and soon stopped altogether. According to Macmillan's statements (kept at the Santiniketan archives), Song Offerings sold 19,320 copies till February 20, 1914: in the next three years, it sold another 18,680 copies. An enquiry showed that in the 65 years, it sold only 20,000 copies in the West.

Tagore's reputation abroad was nothing compared to his vast popularity in his own soil, Bengal. Till 1982-83, the publication division of Santiniketan had sold 3,09,684 sets of Tagore's complete works in Bengali, comprising 30 volumes, with each set currently priced at Rs 1,108. In addition, the West Bengal Government had sold about one lakh sets. Last year, the publication division earned a revenue of Rs 32.94 lakh selling Tagore's Bengali books. His five top-selling titles have sold over two million copies, in addition to the sale of his complete works, 12,846 sets of which were sold last year. Said a Calcutta publisher: "In terms of sustained sale over a long period, Tagore is the most successful author born outside of the West."

Personal loss: Tagore's Gitanjali, completed in 1910, and translated into English as Song Offerings with Yeats' emendations, is a sombre song born out of private grief. He wrote the poems mostly during his wanderings in the family estate at Kusthia district, now in Bangladesh, where he spent months boating down the saffron swirl of the Padma, watching the humanity on the level sand banks - from a distance. At the back of the poems was a series of bereavements: he lost his wife in 1902; his daughter, Renuka, died in 1903; his father died in 1905; his younger son, Shamindranath, died in 1907.

The personal sorrow was heightened by public attacks. He was the butt of the radicals' criticism, the result of which was his bitter comment on terrorism in Home and the World(Ghare Baire—now being filmed by Satyajit Ray). He was also the target of ridicule of the anti-Brahmo fanatics, a provocation which drew him more and more towards religious preaching.

While writing Gitanjali, Tagore was also fighting an emotional and intellectual battle on every front. When he finally got the Nobel his distrust of the Bengali society was multiplied. Days after the award was announced, when a reception was given to him at Santiniketan, his address was palpably rude. Said he: "I'll not drink the toast of goodwill and friendliness that you've offered me. I'll merely set my lips on the glass." Despair was sublimated into a vague wanderlust, the temptation to preach and be acclaimed as a "messiah", a "sage from the East", a "rishi". Nirad C. Chaudhuri, in an article, had observed that there were two Tagores: the one before the Nobel Prize who was a passionate poet; and the one after the Nobel Prize who pontificated from Olympian heights, did not mind being addressed as 'Gurudev', and dressed himself in a quaint robe. "It is the second Tagore", laments Ghosh, "who blundered his way across the continents, walking into politicians' traps, and behaving like the innocent abroad." And later, much against the advice of his lifelong friend, Romain Rolland, he accepted an invitation to Fascist Italy, and even sang a paean of praise for Mussolini whom he called "shy of publicity—like me".

The Nobel Prize might have come to Tagore by a quirk of destiny, with political factors, altogether unfathomable by the poet, shaping the decision. But, by raking it up, Ghosh has touched a raw nerve in Bengal where Tagore is often regarded not just as a poet but as a symbol of community pride, a sort of mascot of Bengali cultural dominance, once a reality but now badly threatened. "Debunking respected people is Bengal's main pastime - and Nityapriya is no exception to the rule," said Bhabatosh Datta, an eminent literary historian and university don at Santiniketan. But a band of researchers and academics, with views less clouded by patriotic fog, admitted that there were vast stretches of "grey areas" in the events that led up to the awarding of the 1913 Nobel Prize for literature.

In preparing his instalment of research papers on the riddle, Ghosh promises to search the Swedish sources which perhaps can help solve the mystery. Quite unfazed, he said: "I can't give away my right to question. Tagore never gave away his."

(The article was published in the INDIA TODAY edition dated October 31, 1983)

Subscribe to India Today Magazine