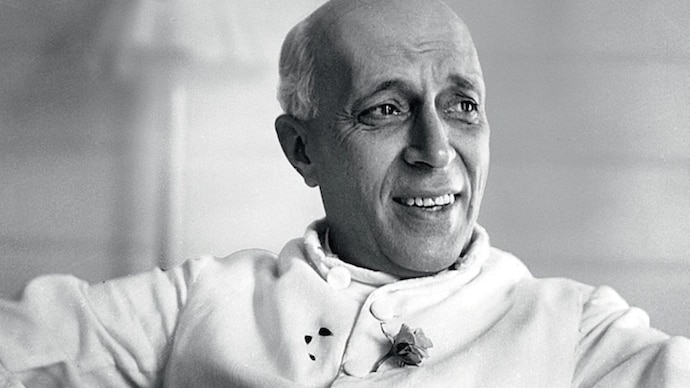

From the archives: How Jawaharlal Nehru foiled a British plan to Balkanise India

On our first prime minister’s death anniversary (May 27), INDIA TODAY presents extracts from M.J. Akbar's magnum opus ‘Nehru: The Making of India’

Gandhi was the Mahatma, Jawaharlal was the disciple-builder: the heir of the Mahatma, the genius who could be trusted with a priceless and historic legacy.

Gandhi was the Mahatma, Jawaharlal was the disciple-builder: the heir of the Mahatma, the genius who could be trusted with a priceless and historic legacy.

Gandhi was hardly so naive as to believe that Jawaharlal would ditto everything he said. Far from it. Differences between them on economics and socialism were too open for either to pretend they did not exist. Even in his glorious speech at the 1942 AICC the Mahatma laughed and said Jawaharlal liked to fly, while his concepts of development were more rooted to the village hut and the charkha.

Then why did Gandhi choose an heir who broke off from the master on his own tangents, when others would have been more loyal to detail? Clearly because it was Jawaharlal who could be the best guardian of India, who was closest to Gandhi's understanding of modern Indian nationalism, of the principles which could keep this complex nation united.

He had to put idealism into practice, a difficult task at any time but never more so than as inheritor of a nation torn into two by mischief and mistake. There were dangers everywhere, not the least of them being within. There were many Congress leaders whose lips paid service to secularism, for instance, but whose hands were tainted with blood.

What greater tragedy could there be therefore that Jawaharlal's most vicious critics pin partition on to him - and very often him alone. Enough evidence has now become available to nail this propaganda; if anything Jawaharlal saved India from a worse fate in 1947, and then protected the unity of what was left of India with a wisdom that must place him among the greats of history.

Any norm of behaviour demanded that if linguistic states were to be the pattern for the internal geography of the country, then a "Gurmukhi" Punjab should also be formed - but Jawaharlal refused to allow any such thing. He knew what use could be made of such a geography by theocrats determined to build a secessionist movement. Punjab was divided only after his death; we are now reaping the consequences. Jawaharlal was accused of abusing human rights in Nagaland; once again, he did not care, because if this was to be the price to be paid for Indian unity, then, so be it.

In Tamil Nadu language became the bedrock of a secessionist struggle. Jawaharlal's answer: he would declare a war if necessary against those who wanted Dravidistan. And all the while, even as each day became an endless struggle against problems, he never lost the capacity to find time to be a man with a sense of love, fun, intellect, banter. His life is a beautiful rainbow, like the one which appeared in the Delhi sky the day he became Prime Minister of free India. And even though the end of his life saw one of his great mistakes of perception, the trust in China, slide into humiliation and defeat, history will still grant him, on balance, the epitaph which his Bapu had foreseen: the nation was safe in his hands.

—M.J. Akbar

EXTRACTS FROM Nehru: The Making of India by M.J. Akbar

Plan Balkan

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, the strongman of India, had accepted the idea of partition even before Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, the romantic. Rao Bahadur Vapal Pangunni Menon's (1894-1966) memory fails him just a little in his book. Transfer of Power, as to whether it was in December 1946 or January 1947 that he convinced his favourite minister, Patel, that a united India was an illusion, that Jinn ah would never agree to anything except Pakistan, and that it was better to save what could be saved of India rather than 'gravitate towards civil war'.

Menon's view: keep the predominantly non-Muslim parts of Punjab, Bengal and Assam, accept dominion status in the transition phase before a Constituent Assembly could produce the basis for full freedom, deal with the princes without British interference and take over full power as soon as feasible. This, in fact, was what partition was all about, a scheme which Menon calls his plan. After Patel' s broad concurrence, Menon forwarded it that winter to Pethick-Lawrence with Wavell's permission. Mountbatten saw this plan before he left London for India. But the British were not going to leave without one last stab at something infinitely worse.

The Mountbattens took a short trip to the hills of Simla as another fierce summer descended in the first week of May. Nehru, along with Indira and Krishna Menon joined them as their personal guests on 8 May and were put up at the Viceregal Lodge. It was an ugly and uncertain time; no one knew quite what was happening, or what would happen. In the chaos of competing ambitions, everyone kept their demands high, their expectations low, and tried to bridge the gap with clamour. Some of the stronger princes thought they could get away with independence in the confusion - and the feudal desire cut across religious lines.

The Rajputs of Kashmir or Jodhpur were as keen to keep their estates as the Nawabs of Bhopal or Hyderabad. Voices on the extreme wings of the Akali movement had been raised in favour of an independent state - Khalistan. Trapped between the League's Pakistan and a withering Congress, the Pathans of the Frontier sought independence in preference to merger with Pakistan. Suhrawardy set up a momentum for an independent Bengal, an idea which Jinnah did not mind much because it meant another part of India was lost to Gandhi and Nehru. He told Suhrawardy that he would prefer the Balkanization of India after he got his Pakistan in the north-west; Suhrawardy could keep his Bengal. Jinnah's doctor, J.A.L. Patel, who kept those X-rays in his office safe to protect the dangerous secret, had told him after a seizure in May 1946 that he had only two years left before the lungs gave up.

Now only one year remained, and Jinnah wanted his dream before he died. One of the most extraordinary suggestions of that time, however, was made by Brigadier (later General) K.M. Cariappa, who on 9 May called on Lord Ismay and suggested that the British hand over power to the Indian Army in June 1948, with either Nehru or Jinnah as the commander-in-chief (Ismay to Mountbatten, 10 May 1947; Ismay adds: 'It is hard to know whether Cariappa in putting forward this idea was ingenuous and ignorant or ingenuous and dangerous.')

On 2 May, Lord Ismay and Sir George Abell flew to London with what is known as Mountbatten's First Draft Plan for the transfer of power to obtain the final approval of the British Cabinet. Mountbatten wanted this by 10 May, so that he could put in a week's preparation; he had marked out 17 May for separate meetings with the princes and the leaders of the political parties, during which he would reveal his plan. The princes could be pressured to accept. But if the politicians did not agree, and could not offer an alternative, Mountbatten had decided he would simply hand over power on the basis of this plan and quit. By 10 May word came from London that the Cabinet had approved the plan, with some minor modifications.

On the evening of 10 May, Mountbatten and Nehru retired to the Viceroy's study after dinner for a convivial chat over a glass of port, quite the normal thing to do in British etiquette. They were alone. Mountbatten says that he decided to show Nehru a copy of this secret plan on a 'hunch'. He was not supposed to, of course. On 11 May in a secret telegram to Lord Ismay he explained: "Last night, having made real friends with Nehru during his stay here, I asked him whether he would look at the London draft, as an act of friendship and on the understanding that he would not utilize his prior knowledge or mention to his colleagues that he had seen it." It was so obviously a sincere gesture from a man of goodwill, who was still perhaps unaware of the extraordinary dimensions of all the decisions waiting to be taken. His staff was strongly opposed to showing the plan to Nehru; they argued that it would be a 'breach of faith' to reveal it to Nehru in advance without showing it to Jinnah too. But perhaps they understood how Nehru would react.

According to this plan, the provinces would initially become successor states, and inevitably this would influence the negotiating powers of particularly the larger princely states, which in any case would have the right to strike deals with the Centre before integration into the Union. The government in Delhi would be weak; with power being transferred to so many different points in the country, it was difficult to see how an ineffectual and contradiction-ridden central government could prevent the civil wars and chaos that would break India into chunks, large and small. (We need to remember that, even after the partition that came, Hyderabad, Kashmir and Junagadh remained outside Delhi's control.) At least a dozen confused nations would emerge, at the very minimum, through this plan. Kashmir, Bhopal and Hyderabad could easily have become independent, not to mention Travancore.

There could have been an independent Bengal, and there certainly would have been two Punjabs. The fissiparous tendencies that this in turn would generate can only be imagined. All this was going to be unveiled on 17 May. The ifs of history sometimes stagger one. What if there had been another Viceroy, hostile to Nehru? What if Mountbatten himself had not been sympathetic to the idea of Indian unity? One must appreciate that even he, the most pro-Congress Viceroy of all, had become persuaded that there was no other way to quit India; what if it had been an imperialist like Wavell still in charge? And the biggest if of all: if Mountbatten had not followed his 'hunch'? But Mountbatten went against the advice of his administration to break this historic secret to his friend, at the cost, no doubt, of what many saw as the long-term British interest.

Nehru did not have the remotest suspicion about what he was going to see when he took the file Mountbatten proffered. They continued their conversation, and he began reading it only when he had returned to his bedroom. He was horrified. Shaking with rage, he stormed into Krishna Menon's room, unable to compose himself. He felt cheated, betrayed. So far the only plan the British had discussed with him had been V.P. Menon's, which of course had Patel's approval too. On 8 and 9 May they had formally discussed these proposals at meetings which included V.P. Menon. But even this Indian ICS officer did not breathe a word about the alternative scheme which was certain to Balkanize India, because he was under strict instructions not to.

Theories of conspiracy are no longer fashionable, but if the reader has another word for it, he or she is welcome to use it. As recently as that very morning, on 10 May, details were being discussed formally between Nehru, Mountbatten, Mieville, V.P. Menon and Crum at the Viceregal Lodge. The minutes of the Viceroy's eleventh miscellaneous meeting, which started at 11 a.m., begin:

His Excellency the Viceroy explained that Rao Bahadur Menon had been working on a scheme for the early transfer of power on a Dominion status basis long before he (His Excellency) arrived in India. He said that he would like to give Rao Bahadur Menon an opportunity of explaining the outline of his scheme to himself and Pandit Nehru together. Rao Bahadur Menon said that he had mentioned the scheme to Pandit Nehru the day before: and also four months previously to Sardar Patel. Both had appeared extremely anxious for the early transfer of power.

At that meeting Nehru accepted transfer of power on the basis of dominion status, and though he claimed that the only real difficulty would be in regard to Pakistan, he said it was now clear Pakistan would have to be conceded. Menon said power would broadly be handed over to two central governments, with their own governors-general, with government on the basis of a suitably amended Government of India Act 1935, till the constituent assemblies could work out their own constitutions. Mountbatten remarked that this process should not be too difficult.

Mountbatten then officially wrote to Nehru:

I have now reached certain conclusions with which I have reason to believe H.M.G. will agree. I should like to have a final talk about these conclusions before they are announced and I am therefore inviting the following in addition to yourself, to meet me round the table in Delhi at 10.30 a.m. on 17th May: Sardar Patel, Mr Jinnah, Mr Liaqat Ali Khan and Sardar Baldev Singh.

The States Negotiating Committee got a differently styled invitation: at 10.30 Saturday 17 May the Viceroy proposed to start the timetable, and end it with an announcement in Parliament at 1600 hours Tuesday 20 May. A delay of forty-eight hours might be conceded, but no further, as Parliament would rise for the Whitsuntide recess on 23 May.

When V.P. Menon saw Nehru on the morning of 11 May, he recalls in his memoirs, 'I found that his usual charm and smile had deserted him and that he was obviously upset.' It was a civil servant's understatement. But Nehru was in no mood to talk to a civil servant. He rushed a 'Personal and Secret' letter to Mountbatten. The proposals, he said, had 'produced a devastating effect upon me...The whole approach was completely different from what ours had been and the picture of India that emerged frightened me...a picture of fragmentation and conflict and disorder, and, unhappily also, of a worsening of relations between India and Britain.'

Nehru could not wait to 'give you some indication of how upset I have been by these proposals which, I am convinced, will be resented and bitterly disliked all over the country' (Transfer of Power, Vol. 10, pp. 756-7). He sent a long note later, in which he charged London with completely abandoning every previous decision and pledge, of virtually scrapping the Constituent Assembly, of vitiating the central authority which could protect the nation and of engineering the Balkanization of India through successor states which would conclude treaties with Delhi on one side and His Majesty's Government on the other, breeding a rash of Ulsters on Indian soil.

Nehru's violent opposition shook Mountbatten. However, he was now, as he told V.P. Menon, glad he had shown the draft to Nehru and admitted that it would have been disastrous if he had not done so. Menon advised that the best course now was to return and proceed according to his plan. At 11.30 on 11 May a meeting was called by the Viceroy - Jenkins, Mieville and Erskine Crum attending - to discuss Nehru's 'most disturbing' response. (Incidentally, item 3 of this meeting reveals how the Muslim League used power and why it so desperately wanted it. I quote from the Minutes of the Viceroy's Twelfth Miscellaneous Meeting: 'His Excellency the Viceroy asked Sir Evan Jenkins why the Nawab of Mamdot had asked to form a ministry in the Punjab. Sir Evan Jenkins explained that the Nawab of Mamdot was a very stupid man. He was under the influence of some younger men, who were in a fanatical mood. They evidently thought if the Muslim League could take power, they would be able to withdraw the proceedings which were being taken against Muslims and to use the police force, which was 70 per cent Muslim, to suppress the Sikhs.

Mountbatten then met Nehru alone and agreed that Jinnah would get his Pakistan, with Punjab and Bengal truncated. But power in the rest of the country would be handed to only one central successor government.

Friends and lovers

The first Vicereine whom Jawaharlal Nehru charmed was Lady Eugenie Wavell, but since she was old, fat and motherly there was never any gossip. After his first long talk with Wavell, on 2 July 1945, Jawaharlal had 'stopped to tea with Q., Archie John and the staff; and they all like him' (from Wavell's Journal; he used to call his wife Queenie, hence the Q.) Nehru would swim in the Viceregal Palace during Wavell's time too, but a buzz was heard only when Lady Mountbatten shared the pool. Nehru was far more intimate with the Mountbattens, and enough has been said about their personal friendship for there to be much need for reiteration here.

However, everyone wants to know the answer to the Great Question: was the Edwina-Jawaharlal relationship platonic or not? Mountbatten's favourite authors Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre discreetly skirt the issue in their book tingling with revelations about others, Freedom at Midnight, in what is certainly a deferential gesture to the Earl. Mountbatten's official biographer Philip Ziegler is dehcate towards the Lady in his classic Mountbatten (1985): 'Her close relationship with Nehru did not begin until the Mountbattens were on the verge of leaving India.' Just enough said, and a very good point made: that the politics of the transfer of power had very little to do with the quality of this close relationship.

The nearest this author has come to an answer to the Great Question is this lovely story from Rusi Mody, who has capped a brilliant executive career as the powerful chief executive of the mammoth business empire, Tata Steel. He had met, said Rusi Mody, Jawaharlal thrice - and each time Nehru did not speak a word to him. The first occasion was during a visit Nehru made to the steel factory at Jamshedpur. As a junior executive, Rusi Mody stood at the bottom of the receiving line and got a silent handshake before the great man continued to the next person.

The second time was during the meal that day. Nehru was sitting at the VIP table, and Rusi was, along with other juniors, serving. He went up to Nehru and asked if he would like more chicken. His mouth full, Nehru nodded a silent thank you and returned to his food. The third occasion was at Nainital, where Sir Homi Mody was governor of UP after freedom. The Prime Minister had come to the hills for a short holiday and was staying with the governor.

Sir Jehangir was very pukka, and when the gong sounded at eight he instructed his son to go to the Prime Minister's bedroom and tell him dinner was ready. Rusi Mody marched up, opened the door and saw Jawaharlal and Edwina in a clinch. Jawaharlal Nehru looked at Rusi Mody and grimaced. Rusi quickly shut the door and walked out. Once again, not a word was exchanged.

Be it on record that the first Prime Minister of India and the last Vicereine of India came promptly to dinner.

When the Mountbattens came to Delhi their marriage was already in trouble. The burden of this job did not help matters. Moreover, Edwina wanted to be as active a Vicereine as her husband was Viceroy, and both were determined to leave a very good impression. One of the first things they did on arrival was to cut the portions served during their meals as a gesture to the famine still stalking India, an idea that would not have occurred to Wavell. They also vastly increased the number of Indians on their guest-lists. Within a fortnight of their arrival they even had Aruna Asaf Ali for tea. Violently anti-British, she needed a prod from Gandhi to accept, but once she met Edwina the two became very good friends. The Mount battens tried to woo Jinnah too, but the initial response was cold.

In contrast, both found Nehru eloquent, warm and human. Nehru had been impressed by the political sense and personal regard the Mount battens had shown in Singapore; in Delhi the relationship flowered into a genuine friendship that aroused all manner of suspicion. Their relationship is best caught in a photograph taken by Henri-Cartier Bresson in Delhi in 1948. Mountbatten, in full white admiral's uniform, stands at ease in front, while a step behind him, Jawaharlal and Edwina are laughing loudly at a shared joke: Edwina's laughter circumscribed by some British reserve, but Jawaharlal laughing whole-heartedly, stooping naturally with the effort but looking still at Edwina's face.

The accusation has been too often made, however, that the personal friendship between the two influenced the course of political events. Jinnah gave currency to it first, in his private-public accusations of Mountbatten's 'favouritism' towards Nehru. From some Congress quarters the virulence was no less vicious, with allegations made of a Nehru-Mountbatten conspiracy to solve the problem quickly, using partition as the easiest recourse, so that the ageing Congressmen could get their day in power.

Part of the hostility, at least on the Congress side, surely also derived from an inability to appreciate the nuances of a Western attitude to man-woman relationships. Nehru never believed in Gandhian abstinence and, as he once remarked in his Autobiography, was amoral about sex. Certainly after Kamala's death he had close friendships with women. His love-letters to Padmaja, in particular, are often quite touching and honestly sentimental though never soppy. The appendix of Vol.13 of Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru, 1972, contains a good selection of such letters to 'Bebee dear'. On 2 March 1938 Nehru wrote to Padmaja from Lucknow:

You made me promise to write to you, Foolish one, as if a promise was needed, or as if a promise means anything. Would you have me write to you just to keep that promise even though the desire was lacking? And could you prevent me from writing, short of commanding me to do so and my believing in your command, if the desire to write to you moved me? I shall write to you, as I have written in the past, even when you have not replied. For I write, selfish and self-centred as I am, to please myself, though in my vanity I imagine that I might be giving you some pleasure also. You will not write to me, you tell me, lest you say something which might hurt. A word of yours has power to hurt, but have you thought of the pain of having no word from you? Have you thought of the loneliness that is my life, of the shell in which I live, encompassed and cut off, and from which I seek escape in activity?

Ending with 'My love to you', this billet-doux has a flourish as a postscript: 'The flowers are aflame and send you greetings.' But it is the beginning which is a true gem. It was written in reply to a rather long personal telegram from Padmaja. Nehru begins: 'My dear, your telegram has reached me. How foolish and womanlike and extravagant. Or was it a kind of prayaschitta or atonement for having made love to Subhas?' The two middle-aged heroes, Nehru and Bose, were obviously competitors in more than politics.

Though edging towards fifty in 1937 Nehru was quite infatuated by the daughter of the family friend, Sarojini. On 18 November 1937 he wrote to Padmaja from Allahabad:

How terribly near you are all the time to me since the Ajanta Princess (a representation of the sculpture of the Ajanta caves) has come and taken possession of my room. Why is it that I think of you whenever I look at it?.. How old are you now? Twenty? Oh, my dear, how infantile we are even though the years steal over us. How I long to see your dear face.

Twenty was obviously a personal joke, for Padmaja was born in 1900. On 29 September 1937 Nehru warned her to mark her letters to him 'Personal' to save them from being read by his secretary. The affair continued for many years, maturing gently with time. On 15 December 1940 Nehru wrote to Padmaja: 'It was good to see you. Keep growing younger and thus make up for those who grow older.'

A charismatic personality's reputation is rarely safe in his lifetime: after it, any scoundrel can mock, through the well-known tactics of hint, nudge and half-suppressed smile. Since such stories have become part of the Nehru legend it is necessary for a biographer to confront them, rather than choose the easier option of evasion. Three points, however, do stand out. First, that Nehru was not a hypocrite: he made no secret of the fact that he lived by a value system which did not consider sex to be a moral sin. Second, Gandhi, who was sharp enough to know what was going on, never demanded brahmacharya from a man he nurtured as his heir.

This could only be because Gandhi was convinced that Jawaharlal never allowed his private life to interfere with his public one. Third, the people of India could not care less. The propaganda about Nehru's 'affairs' was carried out by his enemies (in the Congress more than outside) from the time of the 1937 elections onwards in the effort to poison the masses against him, but the people cheated the gossip-mongers by their indifference to such stories. Jawaharlal Nehru led the Congress in four general elections: 1937, 1952, 1957 and 1962. Over a quarter century, through high drama and low, glorious achievement and stunning, dazing tragedy, he never lost the love and trust of those to whom he had given his life: the people of his country.

Greater than his deeds

Caesars should die suddenly. A slow death hypnotizes them, reduces them. They stare at it, in still fascination. They cannot fight the inevitable, but will not surrender before it either. Jawaharlal Nehru was too proud to be afraid of death, but as he said so often he wanted the end to come quickly: he wanted to work on the last day of his life. The shadow of death fell across Nehru's vision on 6 January 1964. The sixty-eighth session of the Congress had just begun at Bhubaneswar with Kamaraj Nadar as president.

When Nehru reached the venue of the session, named Gopabandhunagar, at 3.30 on the afternoon of 5 January he had some reason for relief: a major crisis in Kashmir had been resolved with the recovery of a strand of the Prophet Muhammad's beard, a relic which was found to be missing from the Hazratbal shrine on the night of 26-27 December. The crowds were there of course along the three-mile route from the airport to the Raj Bhavan, where he was staying, as he drove in an open car. But he was not looking well at all. There was an unhealthy puffiness in the face; the eyes had sunk; and his step was slow. It was little wonder that this session was rife with stories about the succession. The Hindusthan Standard reported on 6 January:

There is a move to create the post of deputy Prime Minister of India. The move has been made by a very powerful section of the Congress High Command. This group has even (sic) their choice for this office. Mrs Indira Gandhi appears to be the first choice for this post. Other names mentioned in this connection include Mr Lal Bahadur Shastri and Mr Morarji Desai.

(Indira Gandhi's popularity in the party was borne out when she got the highest number of votes in the elections for Kamaraj's working committee, but the two senior men were far ahead of her in the prime ministerial stakes.)

They first kept the news secret, but it was no use. Too many people had seen Nehru being helped up by Indira and an aide as he suddenly left the meeting of the subjects committee. The Standard carried a photograph of the incident, which was destined to become famous. On 7 January an official communique at seven in the evening again tried to hide the truth, saying it was only high blood pressure due to strain; he had been advised complete rest. No one was fooled. Jawaharlal Nehru had suffered a stroke. He did not participate in the rest of the session, and his ministerial work was temporarily divided between Gulzari Lal Nanda and T.T. Krishnamachari (who took charge of external affairs). The country sensed what had happened, though Indira Gandhi kept a brave and cheerful face in public. The photograph in the Hindusthan Standard had revealed too much. Telegrams and messages came in their thousands, and when Nehru was fit enough to be flown to Delhi his arrival was kept secret both to stop the crowds and to prevent journalists from taking pictures. Yet the complete rest that the doctors had advised was simply beyond Nehru's temperament.

As soon as he reached Delhi, Nehru asked for a situation report on the horrible riots taking place in Calcutta, with Muslims being killed and driven out of their bustees as had not been done since 1950. Communalism: this cancer which had wasted so much of his life, this awful plague which had swept Delhi at the beginning of his prime ministership, was still consuming him in his last months. Nehru would not rest because he could not rest. Ambassador T.N. Kaul remembers him saying angrily when he heard that Soviet doctors had advised a longer convalescence, 'Let them go to hell. If I lie down in bed for even a week, I know I will not get up!' He began, as it were, to clean his table; he knew that the last phase had begun and did not want to leave loose ends for the successor he would not anoint by naming. In his last weeks he even tried to find a way out of the miserably tangled Kashmir thicket by releasing the Sheikh, involving Jaya Prakash and setting in motion a round of talks which seemed to promise a dramatic denouement. (Pakistan, however, was only playing along, waiting for the moment to strike and try to seize Kashmir by force from an India weakened by China.)

One day in May - no one knows which - Jawaharlal had, as was his habit of so many years, jotted down lines of poetry which appealed to his mood. These were four famous lines from Robert Frost, lines which would become many times more famous when they were found on Nehru's table after he died:

The woods are lovely, dark and deep, But I have promises to keep, And miles to go before I sleep. And miles to go before I sleep.

The last moments

The press conference was originally scheduled for Wednesday 20 May 1964 but was postponed to Friday the22nd. It was his first press conference in six months, the first since the stroke at Bhubaneswar. He seemed fine, but his voice was weak. It lasted only thirty-eight minutes, with just about half an hour for questions, the briefest ever press conference by Jawahar Lal Nehru. As usual, he answered a whole range of questions, but the main concentration was on Sheikh Abdullah's efforts to settle the Kashmir problem. The last question however, was, as Nehru himself put it, a leading one. Referring to a recent television interview in which Nehru had said that he was not grooming his daughter as his successor, a correspondent asked whether it was not preferable that he settle the question in his lifetime. Reclining in his chair, a smiling Jawaharlal Nehru replied, 'My life is not going to end so soon.' There were more than 300 journalists present. They thumped their desks and cheered. Jawaharlal went off to Dehra Dun for his last holiday after that press conference.

There is a photograph of Indira Gandhi with her father taken in Dehra Dun on 26 May. He is seated in an armchair on the balcony, and she is kneeling on the floor beside him, her face towards the camera but her eyes looking down. Jawaharlal is looking back, a little surprised by the cameraman from behind. Perhaps one reads meanings into a moment which were never meant to be, but if ever a photograph could portray the last evening of one's life, this was it. And if ever the love of a father and a daughter could be recorded on mere film, then this must be it. They returned to Delhi that evening.

That night he worked as usual, clearing all the papers on his desk. The night would claim him. The time had come to go to sleep, whatever promises might be left unfulfilled, however many more miles he might have wanted to walk in his beloved India. At 6.25 on the morning of 27 May, his normal time to wake, he opened his eyes in pain. His doctors found a rupture of the abdominal aorta. He soon became unconscious. He did not open his eyes again. At two in the afternoon he was declared dead.

(The book extract was published in the INDIA TODAY edition dated November 15, 1988)

Subscribe to India Today Magazine