Realizing Children’s Rights in Bolivia

The Plurinational State of Bolivia has ratified the 1989 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC, 1989). The country has also ratified the Optional Protocols to the CRC on the involvement of children in armed conflict, on the sale of children, on child prostitution and on child pornography, as well as on a communications procedure. However, the status of children’s rights remains insufficiently protected in Bolivia, where child labor, violence, and child poverty are major challenges.

Children’s Rights Index: 6,99/10

Red level: Difficult situation

Population: 11,67 million

Population ages 0-14: 30%

Life expectancy: 72 years

Under-5 mortality rate: 25‰

Bolivia at a glance

In the center of the South American continent, Bolivia, also known as the Plurinational State of Bolivia, is one of the few states in South America without direct access to the sea. As a landlocked country, Bolivia is bordered to the north and east by Brazil, to the southeast by Paraguay, to the south by Argentina and to the west by Chile and Peru.

Bolivia’s territory is divided into nine regions. Its constitutional capital is Sucre and its administrative capital, where the seat of government is located, is La Paz. The Bolivian population is multi-ethnic. Although the main language is Spanish, the Bolivian Constitution recognizes the existence of 37 official languages. Since November 8, 2020, the President of the Plurinational State of Bolivia is Luis Arce. He succeeded Jeanine Anez (2019-2020) and Evo Morales (2006-2019).

The status of children’s rights in Bolivia [1]

The Plurinational State of Bolivia ratified the 1989 CRC on March 8, 1990. This convention guarantees children the rights inherent to human beings and aims to protect children as vulnerable members of society. It is supplemented by three Optional Protocols, namely: the Convention on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflicts (2000), the Convention on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography (2000), and the Convention on the Establishment of a Communications Procedure (2011). All these conventions were ratified by the Plurinational State of Bolivia in 2004, 2003 and 2013 respectively.

At the national level, the Bolivian Constitution upholds the rights of children by prohibiting their forced labour and all forms of violence against them. It also recognizes the right to education; the right to access to culture and sports; the right to live in a healthy, protected and balanced environment; as well as the right to self-determination of peoples (Constitution of Bolivia, 2009). In addition, the adoption in 1999 of the Child and Adolescent Code has enabled considerable progress in the implementation of the International Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Addressing children’s needs

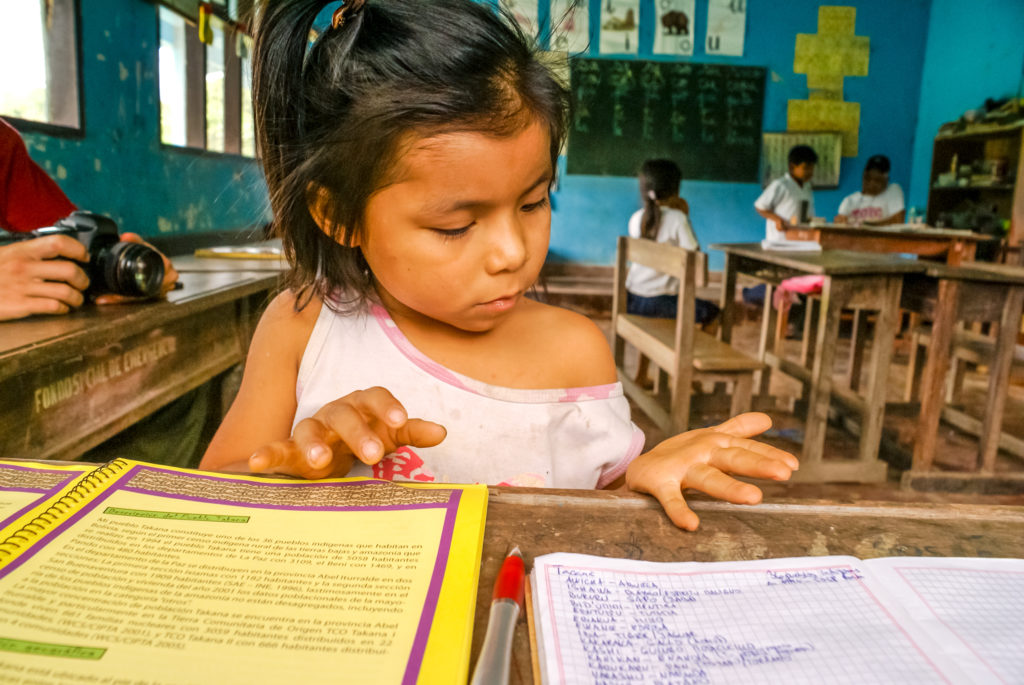

The right to education

Although the Bolivian Constitution guarantees a right to education for all, access to education in Bolivia is marked by significant disparities. In 2019, 74,910 children were not attending elementary school (World Bank, 2019). While there are still inequalities between girls and boys, there is an especially clear divide between urban and rural areas, which struggle to have full access to education. All the more so as the health crisis linked to the Covid-19 pandemic has had a considerable impact on children’s access to education.

Indeed, the Bolivian authorities have chosen to implement a strict lockdown. According to Unesco data, Bolivia is the country that closed its schools for the second longest time in the world, namely 82 weeks (Franceinfo, 2022).

School closures have had a significant impact on access to education. For over a year, access to education was only possible remotely, using digital platforms. However, many families do not have a computer and the necessary equipment at their disposal. Access to the internet and the network, especially in rural areas, is often impossible (RFI, 2022). Exacerbating inequalities, the closure of schools has deprived many children of their right to education. This situation has also impacted the health of children, who express signs of depression, anxiety and distress due to their isolation (Unicef, 2022).

The right to health

The right to health is recognized by the Bolivian Constitution, which, in Article 18, acknowledges the right of every person to access health care without discrimination, and the existence of a single, universal and free health system (Constitution of Bolivia, 2009). However, although it is acknowledged, its effectiveness remains limited.

Indeed, the Bolivian health system is marked by a significant precariousness and by an undeniable lack of means. Many infrastructures are rundown, and human and material resources are insufficient. Moreover, access to health care is marked by large inequalities. Rural and indigenous populations have more difficulty accessing health care, and rarely have access to medical follow-up.

The health crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic revealed the flaws of the Bolivian health system. Hospitals quickly reached the limits of their capacity, and images of bodies lying in the streets, covered with plastic sheeting, left a permanent mark on the minds of the world (RFI, 2020).

These failures of the Bolivian health system lead one to note the youth’s sometimes alarming state of health in the country. In Bolivia, the infant mortality rate was 2.1% in 2020. Nevertheless, this rate has been continuously decreasing for several decades (World Bank, 2020). At the same time, child malnutrition, poorly managed by health organizations, is a real concern. Indeed, one in three children in Bolivia suffers from malnutrition (Unicef, 2020).

This represents a double burden for children, leading not only to deficient growth and developmental delays, but also obesity. Again, girls and boys from rural areas or indigenous families are the first to be affected by this phenomenon (Unicef, 2019). In addition to malnutrition, 27.2% of children aged 6-23 months lack Vitamin A, one of the most common factors in blindness.

Country-specific challenges

Sexual exploitation and child trafficking

Child prostitution is a major issue confronting Bolivia. While young girls may hope to escape poverty by seeking refuge in prostitution, they are often exposed to commercial sexual abuse and become entangled in violent human trafficking. To date, nearly 1,500 children and adolescents are exploited in the sex trade in Bolivia’s megacities, and many of them disappear without a trace (RFI, 2022).

The causes of this phenomenon are numerous and difficult to understand. For many young children, street prostitution is the final escape from extreme poverty. Most children forced into prostitution come from disadvantaged backgrounds, rarely have access to education, and grow up in dysfunctional families. Sometimes it is the parents themselves who force their children into prostitution to contribute to the family income (Caritas).

The consequences are significant. Violence against women and girls has increased dramatically in Bolivia. More than 77% of children are subjected to violence before reaching adulthood. In addition, child prostitution promotes early pregnancy. Human trafficking also benefits from it. Each year, nearly 300 young girls are abducted to be prostituted in the country or abroad (Figaro, 2021).

In response to this growing scourge, Bolivian authorities adopted Framework Law No. 263 of July 31, 2012, creating the Plurinational Council to Combat Trafficking and Human Smuggling. This body is responsible, among other things, for the implementation of the National Plan to Combat Trafficking and Human Smuggling, the provision of specialized care for victims, and the promotion of their professional reintegration.

As they submitted the fourth periodic report under article 40 of the ICCPR, the Bolivian authorities affirmed that two centers specialised in the care of human trafficking and smuggling victims are operational and that the procedures established for investigations foresee the opening of an inquiry by the Prosecutor’s Office and the Bolivian police. In this way, all the necessary investigative acts will be carried out to find the victims, identify the perpetrators, and convict them (Fourth Periodic Report submitted by the Plurinational State of Bolivia, 2019).

However, the reality is sadly often different. Out of thousands of cases of smuggling every year, only a few hundred are reported to the Bolivian police. Of these, 90% do not go beyond the initial investigation phase. As for the rare investigations that lead to a trial, almost none result in a conviction.

Most of the victims’ families feel neglected by the authorities and conduct their own investigations to find their children. The Bolivian police’s corruption is the main obstacle to the proper conduct of investigations, as police officers are sometimes brothel owners themselves. The Human Rights Committee was particularly concerned about the increase in sexual violence in Bolivia and encouraged government authorities to reform the judicial system (UN, 2022).

Violence against children

Violence against children in all its forms, whether physical, psychological or sexual, is a major challenge in Bolivia. During 2021, 46 infanticides were reported and 34,893 cases of violence against children, adolescents, and women were recorded – an average of 95 cases of violence per day. As of May 8, 2022, 15 infanticides had already been recorded (Unicef, 2022).

Such violence is part of a deeply entrenched culture in which the child must be brought up with violence. Violence against children occurs in the home, at school, and on the streets. The health crisis related to the spread of Covid-19 has also been an aggravating factor behind this violence (Unicef, 2022).

This culture runs in total contradiction to Bolivia’s international commitments, but also to its national law. Indeed, article 146 of the Child and Adolescent Code states that: “I. Children and adolescents have the right to be treated well and, in particular, to benefit from a non-violent education, based on mutual respect and solidarity. II. The authority of parents, custodians, guardians, family members and educators must be exercised through non-violent methods of bringing up, teaching and sanctioning children. All physical, violent or humiliating punishment is prohibited.” (Child and Adolescent Code, 1999).

During discussions with the Bolivian delegation, the Human Rights Committee expressed particular concern about the situation of children’s rights in Bolivia and the practice of physical punishments on children. In this regard, the Bolivian delegation agreed that an awareness-raising campaign, particularly in schools, is necessary. It also indicated that a child protection unit within the Ministry of Justice is working to develop a policy to combat abuse and physical punishments against children in schools (UN, 2022).

Child poverty

Bolivia is one of the poorest countries in South America. Nevertheless, the latest figures reveal a decline in poverty in the country by a few percentage points. Indeed, in 2020, extreme poverty amounted to 13.7%, compared to 11.1% in 2021. Similarly, moderate poverty has also decreased by two percentage points between 2020 and 2021, and now concerns 36.6% of the population (RFI, 2022). While these numbers remain high, their downward trend is still a significant achievement – especially in the context of a global pandemic.

Still, poverty remains a deeply rooted plague in Bolivia and a major challenge for the Bolivian authorities. It is also one of the main factors behind all the troubles of Bolivian society. It has an undeniable impact on access to education and health care, and favors the increase of child labor, early or forced child marriages, or child prostitution. Moreover, poverty affects the inhabitants of Bolivia in a very unequal way. People from rural areas and indigenous communities are the most affected by poverty.

During the review of Bolivia’s periodic report, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights asked the Bolivian delegation about the right to an adequate standard of living. In response, the Bolivian authorities pointed out the Bolivian government’s efforts to combat poverty and improve the state’s finances. In particular, they mentioned the introduction of a number of measures to reduce the poverty gap between indigenous and non-indigenous people (UN, 2021).

Child labor

Bolivia is the only state in the world to have legalized child labor from the age of 10. Indeed, in July 2014, the Bolivian parliament passed and enacted a new law allowing children between the ages of 10 and 12 to work on their own. The law, however, prohibited the execution of dangerous tasks for minors under 14 years of age and established a list of prohibited jobs, such as working in mines, in sugar cane fields, or in brick factories (Le Point, 2014). In total contradiction with children’s rights and with international agreements ratified by Bolivia, this law was finally revoked by the Bolivian Constitutional Council in February 2018.

Yet child labor remains a disturbing reality in Bolivia. Nearly one in four young people work to contribute to the family income. From a very young age, children are left to their own devices. From selling candy to working in factories or in the fields, these activities are added to their school hours and often generate a drop in school performance (Franceinfo, 2018).

Poverty is the main reason for child labor in Bolivia, where 60% of the population lives in the informal economy. Hundreds of thousands of families could not survive without their children’s income (Franceinfo, 2018). As a cornerstone of the national economy, child labor is often perceived as “a necessary evil” to fight against family poverty. This is, moreover, the position of the Union of Working Children and Adolescents, which still today fights for the legalization of child labor, hoping to find some legal protection.

This opinion is in no way shared by the International Labor Organization (ILO), which at the time communicated its concerns about the adoption of the 2014 law. According to the ILO, child labor cannot be justified as a “necessary evil” and a means of development. On the contrary, child labor would fuel an intergenerational cycle of poverty: the more a child works, the less likely he or she is to graduate, the less he or she participates in the country’s economic development, and the poorer the country becomes (ILO, 2014).

In addition, Bolivia’s international commitments regarding child labor are not always respected. It should be noted that Bolivia has ratified ILO Convention No. 138 on the Minimum Age for Admission to Employment and Convention No.132 on the Worst Forms of Child Labor. In this regard, the Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations found that while the July 2014 law was indeed declared unconstitutional by the Bolivian Constitutional Court, the Child and Adolescent Code still refers to it (ILO, 2022).

The Commission therefore requested that the Bolivian government “take all necessary measures to adapt the Code of Childhood and Adolescence so that the minimum age of access to employment and work is set at 14 years” (ILO, 2022). However, the Bolivian government’s involvement in this issue could still be improved. Moreover, Bolivia has been considered to be in a ‘serious state of noncompliance’ for failing in its obligation to submit a report (ILO, 2022).

Child marriage

Child marriage is a real problem in South America, and Bolivia is unfortunately no exception. Indeed, nearly 20% of Bolivian girls are married before they reach the age of 18, and 3% of them are married before the age of 15. This problem also affects young boys. Among them, 5% are married before reaching their majority, a situation that places Bolivia among the 15 countries with the highest number of married underage boys (Girls Not Brides).

Unlike other countries in the world, in Bolivia, relationships undertaken by young children usually take the form of an informal union, realised by a shared life, and do not systematically involve a formal or religious marriage. These “marriages” are often an escape route from extreme poverty and allow families to reduce their food expenses. In addition to poverty, child marriages are also the result of indigenous community traditions, some of which set the ideal age for marriage at 13 for girls and 18 for young men (Filles, Pas épouses).

These situations of early or forced marriages, however, are prohibited by both Bolivian national law and international law. Indeed, the Family and Family Procedure Code (2014) sets in article 139 the minimum age to consent to marriage at 18 years (Código de las familias y del proceso familiar, 2014). Bolivia is also bound by the Inter-American Convention on Human Rights, which provides that marriage cannot be concluded without the free and full consent of both parties (American Convention on Human Rights, 1969).

One of the direct consequences of child marriage is the high rate of pregnancy among Bolivian adolescents and young women. This disturbing finding has in fact led the government to implement an action plan, called the Plurinational Plan for the Prevention of Pregnancy in Adolescents and Youth. Implemented in 2015, this action plan noted the following: the teenagers most at risk of pregnancy are those who live in rural areas, have a low level of education and are in a situation of poverty.

Established for a period of 5 years, this plan aimed to create a national platform to promote the prevention of pregnancy among youth and adolescents, as well as to strengthen their care and education (Plan plurinacional de prevención de embarazos en adolescentes y jóvenes, 2015-2020). However, social and economic inequalities persist in Bolivia, and forced or early child marriage remains a serious challenge.

Environmental issues

Bolivia was one of the first states in the world to recognize the rights of Mother Earth. In 2011, the Bolivian government introduced the so-called “Mother Earth Law”. Inspired by the beliefs of the Pachamama, this law grants fundamental rights to nature (right to life, right to water and clean air, etc.) and sanctions its equality with man (Ecolopop).

However, in light of the significant poverty of this state, the exploitation of natural resources remains a significant source of wealth, involving disastrous catastrophes for nature. In this vein, the Bolivian authorities have adopted regulations authorizing the logging and burning of forests.

In August 2021, nearly 600,000 hectares were ravaged by fires in the department of Santa Cruz, in eastern Bolivia. These fires were deliberately caused, the will of the culprits being to transform the forests into agricultural areas (Le Monde, 2021). This practice, also called “slash and burn”, had provoked the anger and outrage of indigenous organizations. The latter had demonstrated their disagreement in vain during nearly 37 days of marches in Santa Cruz (Le Monde, 2021).

During the examination of Bolivia’s periodic report on the implementation of the provisions of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Committee members asked the Bolivian delegation about the measures taken by the Government to address climate change. In response, the delegation indicated that regarding water resources, a training program to share local techniques for sustainable water management had been implemented. It stated that clear commitments have been made to ensure the proper use of national resources and compliance with environmental standards (UN, 2021). However, there is still a long way to go when it comes to environmental rights.

Written by Manon Lanselle

Internally proofread by Aditi Partha

Translated by Karolina Hofman

Proofread by Alex Macpherson

Last updated on June 25, 2022

Bibliography:

Ecolopop, (6 mai 2011), La Bolivie adopte une loi de la terre mère, consulté le 28 août 2022.

Filles, pas épouses, Atlas interactif du mariage des enfants, Bolivie, consulté le 28 août 2022.

Le Monde,(24 août 2021), En Bolivie, des zones protégées parties en fumée, consulté le 28 août 2022.

Unicef, (10 juin 2022), L’Unicef appelle à protéger les enfants contre toutes les formes de violences, La Paz, consulté le 28 août 2022.

[1] This page in no way aims to provide a comprehensive or representative account of children’s rights in Bolivia. Indeed, one of the main difficulties is the lack of updated information on children in Bolivia, most of which is not reliable, representative, obsolete or is simply non-existent.