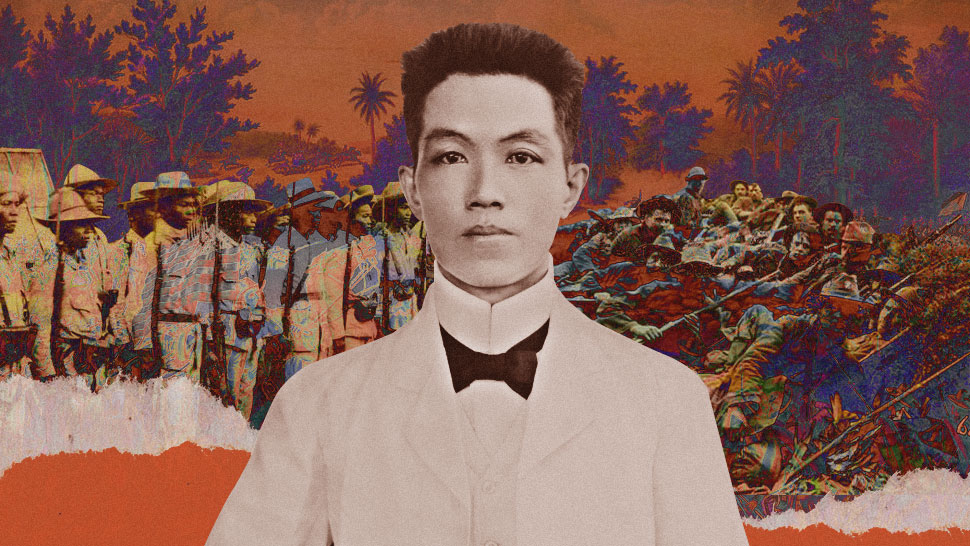

Did Emilio Aguinaldo's Surrender Mark the End of the Philippine-American War?

On April 19, 1901, Emilio Aguinaldo issued a proclamation that broke the heart of thousands of revolutionaries nationwide. “The complete termination of hostilities and a lasting peace,” he said, “are not only desirable but absolutely essential to the welfare of the Philippines.” It was a proclamation of surrender in the Philippine-American War.

Aguinaldo did not write a long speech. He simply said that “accepting” American sovereignty was him “heed[ing] the voice of a people longing for peace,” and that he was serving his beloved country. No matter how he worded it, one thing was clear: This proclamation was the punctuation mark in Aguinaldo’s Republic and its war for independence.

What made Aguinaldo change his mind? And more important, how did the Filipino people take his surrender?

A guerrilla war could have resulted in Philippine victory.

A month before, Aguinaldo was hiding with his family and some bodyguards in the town of Palanan in Isabela. This was the culmination of months of escape and a shift in tactics: The previous November, Aguinaldo sent out a proclamation ending open confrontation against the United States forces and shifted toward guerrilla warfare. The Americans, meanwhile, had already captured Malolos and Central Luzon and were easily closing in.

Militarily, Aguinaldo was in a precarious position. A guerrilla war could have resulted in Philippine victory if he held out long enough. The Americans were notoriously bad at dealing with asymmetric warfare, and were thousands of kilometers away from home. Back in the United States, the American invasion of the Philippines was increasingly becoming unpopular. Figures like Mark Twain led the Anti-Imperialist League and condemned the war, which saw hundreds of American soldiers fight and die for a war that killed thousands more.

All Aguinaldo had to do was hold his cards close and play them right. There might be a chance for victory yet; at least, that was what he thought.

Meanwhile, the Americans were willing to wait him out. Filipino forces were scattered, save for one army in the north commanded by Manuel Tinio. And although the war was unpopular back home, Aguinaldo’s government fostered little love for an increasingly large section of the Filipino people either.

The loss in morale was the result of many different factors. Historians like Milagros Guerrero, Vicente Rafael, and Reynaldo Ileto have pointed out to the increasingly divergent aims of the revolutionary leadership and the Filipino masses who felt the brunt of the fighting. It didn’t help that the Filipinos suffered repeated losses from the American advance, as well as the loss of generals like Antonio Luna and Gregorio del Pilar.

Aguinaldo was captured in Palanan.

American records noted the frequency of Filipino surrenderees as the war raged on. On February 8, 1901, the Americans received a breakthrough: Cecilo Segismundo, one of Aguinaldo’s messengers, had formally surrendered to the Americans. The Americans were, at first, skeptical of Segismundo, but an examination of the letters he had with him proved his identity.

More important, Segismundo revealed Aguinaldo’s hiding spot in Palanan. A plan was then hatched: A group of Filipinos loyal to the Americans would disguise themselves as friendly reinforcements, with the Americans in tow as “captured prisoners.” Once within, they would apprehend Aguinaldo and put an end to the war once and for all.

The false flag operation was a success. Two officers, Filipino turncoat Hilario Placido and Spaniard Lazaro Segovia led a force of scouts from Macabebe and caught Aguinaldo by surprise on March 24, 1901. On his capture, Aguinaldo remarked that he could “hardly believe [himself] to be a prisoner,” and that he was gripped by a “feeling of disgust and despair for I had failed my people and my motherland.”

Aguinaldo was sent to Manila. A month later, he would make his declaration and formal surrender. U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt would declare the Philippine-American war “officially” over on July 4, 1902.

Did the Philippine-American war really end?

It is debatable whether Aguinaldo’s surrender proclamation marked an end to the Filipino’s will to fight for their independence. By all accounts, the Philippine revolutionary government found its continuance through Simeon Ola, Miguel Malvar, Macario Sakay, and others.

But more than that, for many Filipinos, Aguinaldo’s surrender was only the latest disappointment from the Malolos government. For a sizeable section of Philippine society, they saw the revolutionary government, ran by its ilustrados and principalia, as something utterly divorced from the nation’s peasantry. For some, they weren’t any different from the old Spanish land-owning class that came before them.

A lot of peasants were especially disappointed by the Aguinaldo government’s seeming indifference to the plight of the peasantry: landlessness, unfair taxation, and cruelty by the Spanish friars. They saw these failures to act as betrayals to the Katipunan cause.

Worse still was the conduct of some revolutionary generals, who took it upon themselves to undermine authority already established by the peasant revolutionaries. In their eyes, they were the authorized representatives of the Revolutionary Government. For the peasants, who continued the struggle after Aguinaldo’s first surrender in Biak-na-Bato, these “governors” were upstarts who did not understand the struggle.

So, for a significant number of the Filipino people, Aguinaldo’s defeat and surrender did not represent their surrender. Rather, it was the loss of the bourgeois elite, and proof that a revolution composed of peasants and workers must be led by people and an organization rooted in the same.

Revolutionary ambition for an independent Philippines continued after Aguinaldo’s surrender. His generals picked up the guerrilla struggle in their base areas, until they were forced to surrender due to American sadism. In Mindanao, the Moro struggle continued until they too were subjugated by American force of arms.

By the end of the Philippine-American War, over 17,000 American troops were deployed in the Philippines, and resulted in over 250,000 Filipino deaths. Anti-imperialist struggles continued; in America, through the Anti-Imperialist League, and at home, through the labor unions, peasant organizations, and mass movements.

Today, 80 years since, that same struggle continues in various forms. Unarmed and armed, democratic and revolutionary, open and in secret. But what can be said for certain is that the Filipino desire for a truly independent Philippines did not end on April 19, 1901, when Emilio Aguinaldo disappointed his fellow countrymen.

Don't forget to subscribe to the Esquire Philippines YouTube channel.