Introduction

Epilepsy is a chronic neurological disorder in which a group of nerve cells (neurons) in the brain signal abnormally and cause seizures.

- A seizure is an abnormal, sudden, excessive discharge of electrical activity within the brain.

- During a seizure, many neurons signal much faster than normal at the same time (as much as 500 times per second).

- This rush of excessive electrical activity happening at the same time causes involuntary movements, emotions, behaviors, and sensations and the temporary disturbance of normal neuronal activity may cause a loss of awareness.

- Jerking movement, grunting sounds, drooling, and rapid eye movements are associated with convulsions.

- Epilepsy is diagnosed when a person has had two or more seizures.

Status epilepticus

- Status epilepticus is the condition in which a seizure lasts longer than five minutes, or a person has more than one seizure within five minutes, without returning to a normal level of consciousness between the episodes.

- Status epilepticus can be convulsive and non-convulsive.

- Nonconvulsive status epilepticus has a lower risk of long-term injury than with convulsive type.

- People with nonconvulsive status epilepticus may appear confused or look like they are daydreaming. They may also behave irrationally and be unable to speak.

Incidence

According to World Health Organization (WHO), epilepsy accounts for more than 0.5% of the global burden of disease and is one of the most common neurological diseases globally. Low and middle-income countries bear more than 80% burden of the cases.

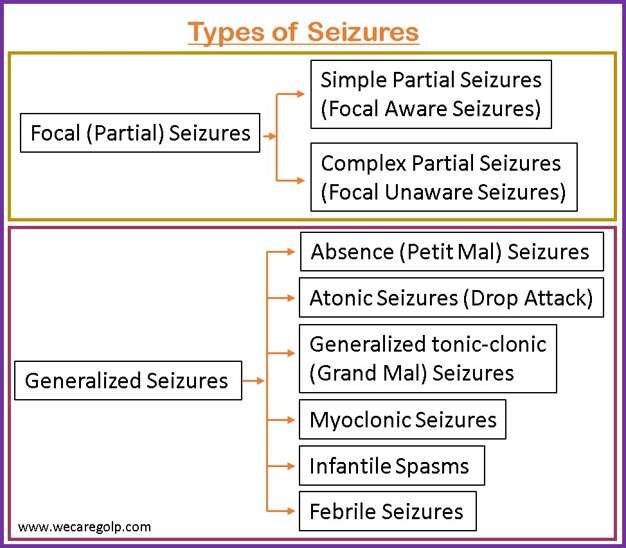

Types of Seizures

The type of seizure depends on the part and severity of the affected brain. The two broad categories of epileptic seizures are partial and generalized seizures.

Partial (Focal) Seizures

- Partial seizures take place when abnormal electrical brain function occurs in one or more areas of one side of the brain.

- With partial seizures, particularly with complex partial seizures, the person may experience an aura before the seizure occurs.

- The most common aura involves feelings such as

- Simple and complex partial seizures are the two types of partial seizures.

Simple partial seizures (focal aware seizures)

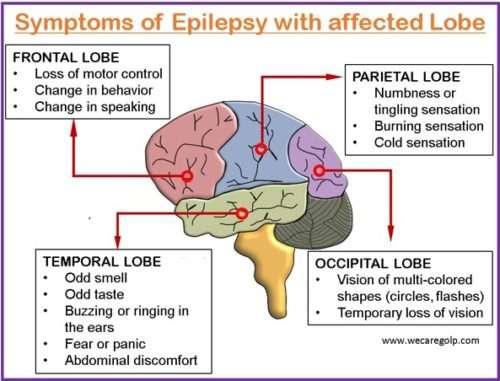

- Different symptoms are seen in the person depending upon which area of the brain is involved.

- The motor symptoms are more common but can be sensory, autonomic, or psychic. Some of the symptoms may be

- Muscle tightening,

- Numbness, tingling,

- Eye movements from side to side,

- Blank stares,

- Hallucination, etc.

- Consciousness is not lost in this type of seizure but the person may experience sweating, nausea, or becomes pale.

Complex partial seizures (focal unaware seizures)

- This type of seizure commonly occurs in the temporal lobe of the brain that controls emotion and memory function.

- This usually lasts 1 to 2 minutes. Consciousness is usually lost during these seizures and the person becomes unaware of what is happening around the surroundings.

- The person may look awake but have a variety of behaviors like lip smacking, gagging, screaming, crying, laughing, or running.

- When the person regains consciousness in the postictal period, he or she may complain of being tired or sleepy.

Generalized Seizures

- The seizure involves both sides (hemispheres) of the brain. There is a loss of consciousness and a postictal state after the seizure episode.

- Types of generalized seizures include the following.

Absence (petit mal) seizures

- There are brief periods of consciousness (memory lapses) or “blackouts” and staring episodes.

- The person’s posture is maintained during the seizure but there may be lip smacking, eyelid movements, chewing motions, hand movements, etc.

- The seizure usually lasts for 10 to 30 seconds. When the seizure is over, the person may not recall the incident but may continue with his/her activities, acting as if nothing happened though. These seizures may occur several times a day and usually start between the age of 4 to 12 years.

Atonic seizures (drop attacks)

- There is a sudden loss of muscle tone and the person may fall from a standing position to the ground or suddenly drop his/her head, eyelid, or the things they hold.

- The consciousness is usually intact. The seizure usually begins in childhood.

Generalized tonic-clonic (grand mal seizures) seizures

- This type of seizure is characterized by distinct phases.

- The seizure may begin with an Aura.

- The tonic phase begins with stiffening or rigidity of the muscles of the arms and legs and usually lasts 10 to 20 seconds, followed by loss of consciousness.

- In the clonic phase, there is arrhythmic jerking of the extremities with hyperventilation which usually lasts about 30 seconds.

- The person may also lose control of their bladder or bowels.

- During the postictal phase, the person may be sleepy, has problems with vision or speech, and may have severe headaches, fatigue, or body aches.

- The person usually wakes up in about 30 minutes but may take longer, especially if they had status epilepticus.

- Not all these phases may be seen in every person with this type of seizure.

Myoclonic seizures

- In this type of seizure, there are rapid movements or sudden jerking of a group of muscles.

- The person may fall as a result of the seizure.

- These seizures can occur in series like several times a day, or for several days in a row.

Infantile spasms

- This is a rare type of seizure disorder that is seen in infants from less than six months of age.

- A high probability of this seizure is when the child is awakening, or when they are trying to sleep.

- The infant usually has brief periods of movement of the neck, trunk, or legs lasting for a few seconds.

- Infants may have hundreds of these seizures in a day which can be a serious problem having long-term complications.

Febrile seizures

- This type of seizure is associated with fever rather than epilepsy but fever may trigger a seizure in a child who has epilepsy.

- These seizures are more commonly seen in children aged between 6 months and 5 years and have a family history of the same type of seizure.

- The seizures lasting less than 15 minutes are called “simple,” and usually do not have long-term neurological effects.

- “Complex” seizures remain for more than 15 minutes and may lead to long-term neurological effects on the child.

Causes/Risk Factors of Epilepsy

The cause of epilepsy is idiopathic (unknown) in most cases. Anything that interrupts the normal connections between nerve cells in the brain like structural, genetic, infectious, metabolic, immune, and unknown causes may result in a seizure:

- Brain damage from prenatal or perinatal causes like loss of oxygen or trauma during birth, low birth weight

- Congenital abnormalities or genetic conditions with associated brain malformations

- Severe head injury

- Stroke that restricts the amount of oxygen to the brain

- Infection of the brain such as meningitis, encephalitis, or neurocysticercosis

- Certain genetic syndromes

- Brain tumor

Signs and Symptoms of Epilepsy

Signs and symptoms of seizure vary according to the type of seizure. Most seizures last from a few seconds to a few minutes.

- Twitching of the face

- Loss of consciousness

- Affected speech

- Temporary loss of the bladder and bowel control

- Slight twitching of all or parts of the body, including arms, hands, and legs

- Convulsions that affect the entire body

- Sudden stillness with a blank stare

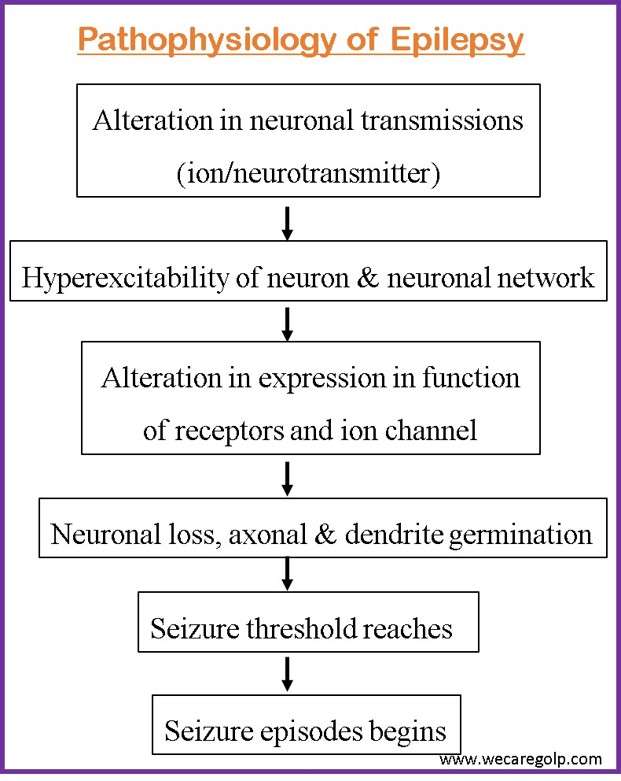

Pathophysiology of Epilepsy

The normal brain continuously generates tiny electrical impulses in an orderly pattern. Chemical messengers (neurotransmitters) help in the transmission of impulses along neurons (the network of nerve cells in the brain) and all over the body.

Diagnosis of Epilepsy

- EEG: to detect abnormal brain waves

- CT and MRI scans: to detect tumors or other structural irregularities

- Functional MRI scans: to identify normal and abnormal brain function in specific areas

- Single-photon emission CT scans: to find the original site of a seizure in the brain

- Magnetoencephalogram: to identify irregularities in brain function using magnetic signals

- Lumbar puncture: to collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for analysis

- Blood tests: to rule out any underlying conditions that could be causing epilepsy (liver function test, renal function test, blood glucose test, complete blood count, etc.)

- Neurological tests: to determine the type of epilepsy in the person

Treatment and management

Medical Management

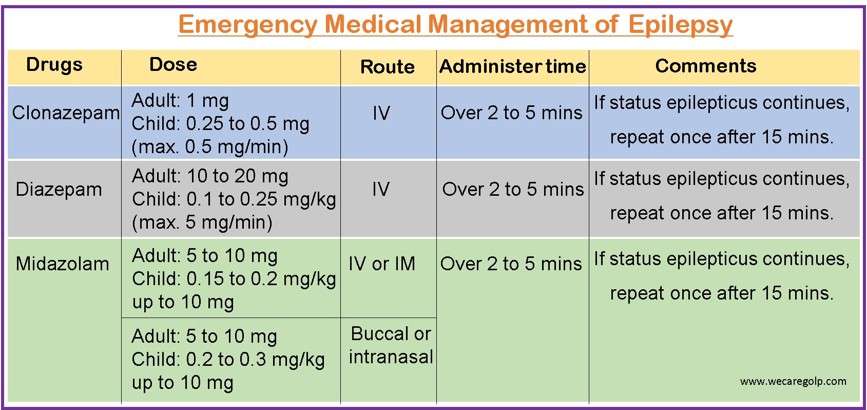

Emergency Management

Most seizures will self-terminate in less than 2 minutes. If they are not controlled, rapid treatment with benzodiazepines or other antiseizure medication will be necessary.

If the seizure continues for 10 minutes despite benzodiazepines, further anticonvulsant loading is required. Even if the seizure terminates with benzodiazepines within 10 minutes further medication is discussed.

Second-line anticonvulsants

- Phenytoin 20mg/kg for adults and children should not be given faster than 50mg/min due to the increased risk of bradyarrhythmia and hypotension.

- Sodium valproate 40 mg/kg up to 3000 mg (avoid in pregnancy).

- Levetiracetam 60 mg/kg up to 4500 mg (is preferred in pregnancy)

- Phenobarbitone (for children) 10 to 20mg/kg IV, not exceeding 100mg/min

For Refractory status epilepticus

- Rapid Sequence Intubation (RSI) and propofol

- RSI and thiopentone (can also use other medicines for infusion like propofol, clonazepam, midazolam)

First aid management

- Loosen clothing around the person’s neck and roll the person on his/her side to keep the airway open.

- Do not force anything even the airway into the person’s mouth.

- Protect from injury by moving sharp objects, such as glassware or furniture, away from the person.

- Do not restrain the person.

- Start treatment with drugs or transfer the person to the health center.

Continuous Treatment of Epilepsy

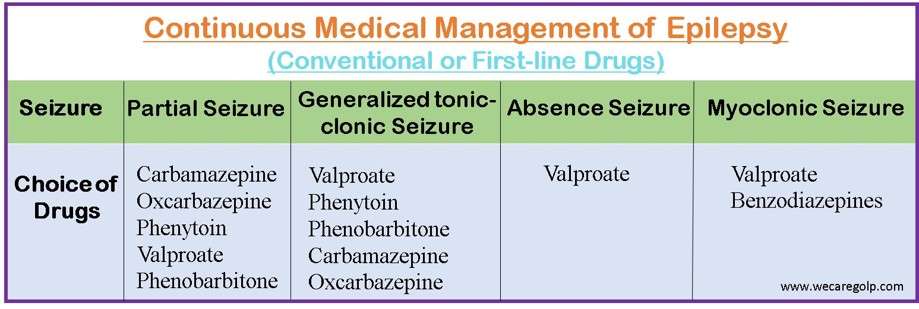

- Phenytoin, Phenobarbitone, Carbamazepine, Oxcarbazepine, and Valproate are conventional or first-line drugs.

- Before initiating treatment with antiepileptic drugs (AED), baseline blood counts, liver enzymes, and renal function test is done.

- If the seizure is not controlled, the dosage of AED is increased to the maximally tolerated limit and also revision of diagnosis is necessary to rule out non-epileptic seizures.

- Alternative monotherapy (single-drug) with a different mode of action or combination polytherapy (multiple drugs) is given when epilepsy is not controlled with a high dose of AED.

- The newer AEDs (Gabapentin, Lamotrigine, Levetiracetam, Tiagabine, Topiramate, Vigabatrin, and Zonisamide) are recommended for the management of epilepsy in people who have not improved from treatment with the conventional AEDs or for whom the older AEDs are not suitable because of intolerable adverse events.

- Withdrawal of AED in most cases is done after a seizure-free period of two to three years.

- The decision is mainly based on the type of epilepsy syndrome and the cause of seizures.

- AEDs are usually withdrawn gradually over several months (at least 3-6 months or longer) because there is a possibility of seizure recurrence during and after withdrawal.

- Moreover, a ketogenic diet (high in fat and low in carbohydrates) is sometimes recommended to help manage epilepsy if medicine alone cannot improve it.

Surgical Management

Some neurosurgical procedures are effective for some patients with epilepsy resistant to drug treatment. The most commonly performed procedures involve anterior and medial temporal lobe resection providing seizure treatment in about 70% of patients.

Vagus nerve stimulation

- This is done in adult patients who are unsuitable for resective surgery.

Deep brain stimulation

- It is done to treat patients with drug-resistant epilepsy who are not candidates for surgery.

Palliative procedures

- Resective surgery: It is the most common epilepsy surgery that involves the removal of a small portion of the tissue from the area of the brain where seizures occur. These could be a tumor, an injured part of brain, or a malformation. Resective surgery is usually performed on one of the temporal lobes (the area of the brain that controls visual memory, language comprehension, and emotions).

- Callosotomy: This surgery completely or partially removes the part of the brain that connects nerves on the right and left sides of the brain; the corpus callosum. The surgery is usually done in children who experience irregular brain activity that spreads from one side of the brain to the other.

- Hemispherectomy: It is a procedure to remove one side of the brain called the cerebral cortex and is usually done in children. Due to the condition present at birth or in early infancy, the person experiences seizures that originate from multiple sites in one hemisphere.

- Subpial transection: It is a surgical technique by which connections of the epileptic focus are partially cut without resection.

Complications of Epilepsy

- Falls may result in injury to the head or bone fracture.

- Risk of accidental drowning when a person has a seizure while swimming or bathing.

- Accidents, when a seizure causes either loss of awareness or control, can be dangerous while driving a vehicle or operating other equipment.

- Seizures during pregnancy pose dangers to both mother and fetus, and certain anti-epileptic medications increase the risk of birth defects.

- Psychological problems like depression and anxiety may be present in the person with seizures.

Prevention of Epilepsy

- Prevents head injury to avoid post-traumatic epilepsy.

- Adequate perinatal care to prevent birth injury.

- Manage fever to reduce the chance of febrile seizures.

- Reduce cardiovascular risk factors, e.g.,

- Prevent or control high blood pressure, diabetes, and obesity

- Avoid tobacco and excessive alcohol use

- Avoid central nervous system infections and parasitic infections (neurocysticercosis).

- Take the epileptic drugs as prescribed.

- Discuss with the doctor regarding other prescribed medicines to make sure that they will not trigger seizures.

- Getting plenty of sleep and healthy living way to cope with stress.

Prognosis

- According to WHO, it is estimated that up to 70% of people living with epilepsy could live seizure-free if properly diagnosed and treated.

- The risk of untimely death in people living with epilepsy is up to three times higher as compared to the general population.

- In low-income nations, three-quarters of epileptics do not receive the necessary treatment.

- About one-fourth of epileptic cases can be avoided.

Summary

- Epilepsy is characterized by recurrent episodes of seizures which are brief with involuntary movement that may involve a part of the body or the entire body.

- Generalized tonic-clonic seizures may result in loss of consciousness and control of bowel or bladder function.

- The causes of epilepsy may be idiopathic as well as structural, genetic, infectious, metabolic, and immune.

- Signs and symptoms depend on the type of epilepsy.

- Treatment and management include first aid, medical and surgical management.

- Prevention can be done by reducing head injuries, infections, and illnesses related to the brain.

- The prognosis is based on the cause of epilepsy and the efficacy of treatment.

References

- Tasker RC. (1998, Jul). Emergency treatment of acute seizures and status epilepticus. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 79(1),78-83. Doi: 10.1136/adc.79.1.78

- WHO(2022) global report on epilepsy

- Klein E. (2019) What to know about epilepsy

- Beghi, E. (2020). The epidemiology of epilepsy. Neuroepidemiology, 54(2), 185-191. Doi: 10.1159/000503831.

- Silvestri L.A. & Silvestri A.E. (2022). NCLEX-RN comprehensive review. Saunders

- Johns Hopkins Health System (n.d.). What is status epilepticus?. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/status-epilepticus