The hastily organized Action Committee, led by a pro-Pakistani lobby, had done their best to discredit and destroy the Indian credibility, and, but for the pious religious leaders of the Valley, Kashmir was all but lost. This forced a rethink of the Kashmir policy by New Delhi and Prime Minister Nehru, never comfortable with the idea of long incarceration of an individual due to lengthy process of law, once again began to have second thoughts about Sheikh Abdullah’s detention.

Another disturbing aspect about the incident was the call by the leaders of Jammu to observe a general strike in the region to protest the theft of two idols from Hindu temples, and the general lack of trust in the government. Many suspected that this new development in the State was a result of Hindu reaction and was triggered by some vested interest to further vitiate the atmosphere. Luckily, the Sadar-i-Riyasat was able to convince the leaders from Jammu to call off the strike. But the threat pointed to the fragile nature of communal peace in the State.

In the Valley, the Moe-e-Muqaddas incident had brought all the fringe forces opposed to India on a single platform. One wing of the Action Committee, formed under the chairmanship of Maulana Mohammad Sayed Masoodi, co-founder of the Muslim Conference along with Sheikh Abdullah, was represented by the followers of Sheikh Abdullah and the Plebiscite Front formed by Mirza Afzal Beg.

Also read: BJP rulebook mentions ‘secular’ more than Congress’. The word is not leaving Constitution

Another wing was of the followers of the Mirwaiz-i-Kashmir, Maulavi Mohammad Farooq and the Action Committee, who were, and had been, vocal opponents of Sheikh Abdullah. Many among this group were fervent supporters of the demand for the merger of the State with Pakistan. With the advent of Sadiq as Chief Minister, these elements had no option but to lie low and wait for an opportune time to strike again.

On the other side of the border, Pakistan too was smarting. Its carefully laid plan to exploit the situation had yielded nothing but disappointment. The religious ploy had been foiled by a few saintly men of Kashmir, who had refused to be part of deceit and lies. But when it came to Kashmir, Pakistan was nothing if not persistent. Kashmir had become its raison d’être. It bided its time and, the summer of 1964 had raised its hope for it. By then, Prime Minister Nehru was no longer in the best of his health. The long years in prison, the struggle for the country’s independence and the deep disappointment at his failure to deal with the Chinese and the consequent humiliation of the defeat of 1962, took its toll on his health.

It was then that he decided to resolve the Kashmir problem. It was a problem in the making, of which he had a fair share of blame. Thus, he concurred with the view to free Sheikh Abdullah. It was preceded by dramatic events in the State with the Sadiq government seen to be committed to the withdrawal of the Kashmir Conspiracy Case and the release of Sheikh Abdullah. Even Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad began to demand his release, and with the atmosphere vitiated by uncertainty, the prosecution witnesses began to waver. On 5th April 1964, Chief Minister Sadiq announced the release of Sheikh Abdullah.

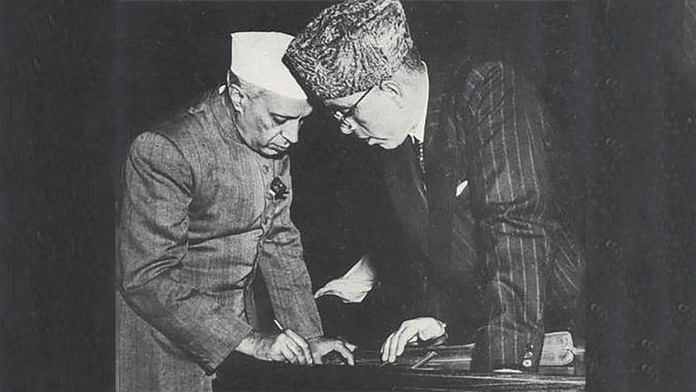

No sooner had this been announced than Nehru invited Sheikh Abdullah to Delhi as his guest. By all accounts, the meeting between the two estranged stalwarts was an emotional affair. There is no denying that both loved Kashmir and wanted to possess it, and, in a way, were rivals in this pursuit. Not much is known of what actually transpired between the two in Delhi, except that they had long discussions. But it was soon announced that Sheikh Abdullah would be making a trip to Pakistan to meet President Mohammed Ayub Khan and achieve a breakthrough. Obviously, this was the Prime Minister’s idea as he wanted Sheikh Abdullah to see for himself the conditions in Pakistan and then decide what he wanted from his association with India. There was an air of anticipation and excitement and both Delhi and Rawalpindi exuded confidence and optimism. Sheikh Abdullah was certain that a deal acceptable to all would be struck.

Also read: When Licence Raj went after Vicks Vaporub in India’s peak flu season

There are two different versions of what happened there. It has been suggested that there was a ‘plan for a confederation between India and Pakistan, with Kashmir as an autonomous enclave between them on the model of Andorra, between France and Spain.’

In Rawalpindi, Sheikh Abdullah was received by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto as well as two prominent Kashmiri leaders, who had migrated to the other side after 1947 and were erstwhile colleagues of Sheikh Abdullah during the Muslim Conference days—Chaudhary Ghulam Abbas and former Mirwaiz of Kashmir, Maulavi Yusuf Shah. According to President Ayub Khan’s autobiography Friends Not Masters, India did propose a confederation but was rejected by Pakistan since it believed that it was a plan devised by Nehru to extend Indian hegemony.

However, this claim was rejected by Sheikh Abdullah in his letter written to President Ayub Khan on 1st September 1967: ‘We had not taken with us any cut and dried proposal concerning Kashmir and, as a matter of fact, Jawaharlal Nehru had not asked us to put across any proposal. We are not made that way.’ It was in Muzaffarabad that the news of Nehru’s death was broken to him and Sheikh Abdullah, in the presence of journalists, including the two Indians, Prem Bhatia and Inder Malhotra, broke down and wept.

Extracted from ‘A Modern History of Jammu and Kashmir: Volume Two — The Karan Singh Years (1949-1967)’ by Harbans Singh. Published by Speaking Tiger Books, 2023.

Extracted from ‘A Modern History of Jammu and Kashmir: Volume Two — The Karan Singh Years (1949-1967)’ by Harbans Singh. Published by Speaking Tiger Books, 2023.