Manoranjan Byapari writes about his life and observations as a servant to a Brahmin doctor.

I had stepped out of my home after dusk. So by the time I reached the Ghutiari Sharif station, it was dark. Electricity had not reached here as yet and the station was lit up by the flickering flame of small kerosene lamps at the top of the lamp posts. Exhausted after my long walk, I lay down on an empty bench and promptly fell asleep. I was awakened by the beam of a torch on my face and a stranger’s voice asking me, “You, boy. Where are you going?” Startled by the light as much as by the question, I sat up, speechless. How was I to know where I was going. All I knew was that I needed to flee from this yawning maw of hunger. I needed to see if the crops of the world had indeed been devoured or whether any remained for me and my tribe. Seeing me speechless, the man repeated his question. Then, perhaps observing my clothes and my emaciated body by the light of the torch, asked, ‘Are you refugees?’All his questions were answered with the nod of my head. Refugee. Is there a word more impoverished or humiliating than this in the Bangla dictionary?

To the people of West Bengal, the words’ refugee’ and ‘Bangal’ are synonymous. And the word ‘Bangal’, a name for people from East Bengal, was also, for all practical purposes, a word of abuse too. Like the adjectives ‘reactionary’, bourgeois, ‘loan shark’, ‘jotedar’, ‘street mongrel’. What a cursed life we had. We call ourselves Hindu and worship idols. For this reason, the Muslims look upon us as kafirs. Because we belong to the lower caste-Namashudra community, the upper Hindu castes treat us with contempt and spit on us. Now that we have come to this land, we are abused for being born where we were—for being Bangals.

There is this Bangal—a novel and strange beast,

Jumps up a tree sans a tail—flown in from the east.

These lines were penned by a Ghoti poet. In the eyes of the Ghoti of West Bengal, the Bangal is always an outsider. The people who have come from another land are now in the process of appropriating their culture, their literature, their jobs and their trade. The hostility was so intense that violence could be sparked off any day.

But it was not as I had thought. This man was a Bangal, not a Ghoti, but not a refugee. He had crossed the border much earlier, had bought a plot of land and a pond here and settled down. An educated man, he knew which magic words would make the refugee child swoon at his feet: ‘Will you come with me? Stay at my home? I will give you rice to eat.’

Rice! It seemed so far back in a distant past that I had tasted rice. White, fragrant, exquisite, beautiful rice. The word ‘rice’ felled this boy, starving since ages. I followed him. On the way, he told me why he would give me the rice. I would need to look after the few cows he owned, give them their food, clean out the shed and other small chores like these. The man was a Brahmin by caste and a doctor by profession. He had come to this land as a result of Partition but had not come in as a refugee. He had not stayed at refugee camps or taken over land forcibly but had built his own house on land purchased with his own money. He appeared mighty proud of this. So now I came to learn of yet another division among humanity, besides the many I already knew, between the Bangals who had crossed over to this side: those who stayed as refugees in colonies and those who did not.

In the short life I had led till then I had not come across any bamun-kayets. As a result, I had little idea of the varna system or its discrimination. While a Brahmin priest would be called in by our community to utter the sacred mantras for a wedding or a funeral, that sole Brahmin among the many Namashudras would remain prudent and not flaunt his caste supremacy. It was my entry to this house that showed me for the first time the ugly side of our Hindu faith and our position within its social system. I was a Namashudra, that caste group which had earlier been called Chandal. These people knew this and treated me as a dirty detestable animal. The plate from which I ate was an old and twisted one on which the lady of the house would let fall the rice and vegetables from a considerable height so as to evade my polluting touch. I would take that food and sit in a corner of the courtyard like a beggar. This plate could not enter the house henceforth and so, after washing it, I would keep it in the cowshed. That was also the place where I slept, on a few sacks of ghute, the fuel made out of dried cowdung. The stench of the cows’ urine and the bites of the mosquitoes would not let me sleep much during the night. It was during the day when I took the cows out to graze that I would get my sleep, under a tree. It was this sleep that earned me a savage beating one day when the cows moved too near the railway tracks and, frightened by the whistle of an oncoming train, ran helter-skelter. One caught its hoof in a hole on the ground and fractured it.

The area of Ghutiari Sharif is a Muslim-dominated settlement and houses the mazhar of the pir, Gazi Baba. Many small trade and business enterprises had come up around this popular mazhar and there were groups of Bihari Muslims settled here. Unlike the Bengali Muslims, the Bihari Muslims were not the timid ‘vegetarian-type’. A group of uprooted people who had fled across the border had been settled here too, beside the railway lines. Members of a certain political party visited them on and off, keeping their fresh wounds alive with intermittent provocation. There was therefore an atmosphere of suppressed tension between the two communities and any spark would ignite the fires of anger and resentment. The doctor, being an intelligent man, was of the opinion that he should keep good relations with the influential members of the Muslim community. To this end, he invited over to his house a few of the leader-like Muslims of the area to treat them to that special homemade delicacy payas, which Hindus prepare on special occasions. If in the near future, a riot did break out, this payas he believed would tide him through those difficult days. But the doctor’s wife was ignorant of such clever strategies. Furious at the idea of having to entertain people from the very community that had compelled them to leave their homeland, she grumbled and raged at the idea of those cow-eating Muslims coming and standing in her courtyard, sitting on her veranda, feeding on her payas. But the doctor paid no heed to her grumblings and invited his guests on to the veranda, a place even I, his co-religionist, was never allowed to enter. I have heard said that something like this would often happen in the times of Mughal rule. The lower-caste individual who would be denied the respect of a human being from upper-caste Hindus would be treated with courtesy once he had converted to Islam; after all, the person then belonged to the sovereign’s faith.

Be that as it may, the real trouble in this event began after the payas-eating was done. Once they had left, the doctor’s wife dropped her enforced reserve and screamed herself hoarse at her husband’s lack of prudence. She shouted to me to wash the utensils they had eaten upon, to sprinkle dung-water all around the courtyard they had stepped upon, granting me a position more acceptable than that of the Muslims. One among the invited Muslims would always carry with him a small radio set which he had mistakenly left behind in the doctor’s house. Since it was switched off, it had sat quietly in a corner without anybody noticing its presence. A little way from the house however, the Muslim had realized his mistake and returned to retrieve his possession. But the loud tirade from the doctor’s wife reached his ears, preventing him from stepping into the house again. Nobody saw him but me. I had gone to fetch water from the pond and saw the man standing motionless in the hazy moonlight, stunned with humiliation. His eyes were aflame with anger, the kind of anger that burns and destroys communities. I knew then that the payas that they had had today would not sit easy in their stomachs. It would disgorge itself one day in anger and hatred. For love gives birth to love just as hatred gives birth to hatred, and it was hatred with which they were returning today. There was no escape. For centuries, this ill-fated land had humiliated and tormented one community of people in the name of caste and another community of people in the name of religion. A day would come when in tears and sighs they would be paid back in their own coin.

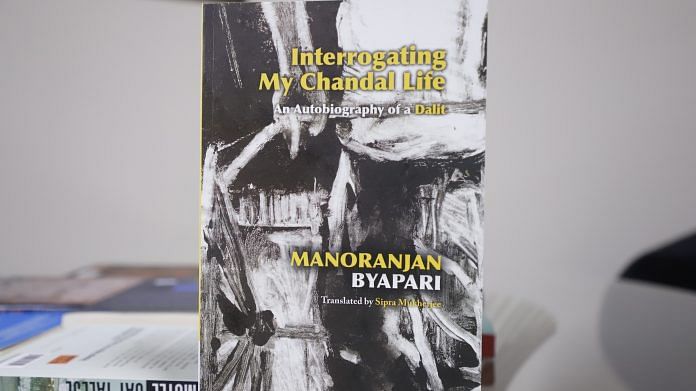

This excerpt is from the book “Interrogating My Chandal Life An Autobiography of a Dalit” by Manoranjan Byapari, and translated by Sipra Mukherjee. It was published by SAGE Samya

Byapari was an “active” Naxalite in those bloody, turbulent days of Kolkata’s history, at odds with the CPM and its power structures. A teenaged refugee from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), Byapari “escaped” the destitution of his shanty in Kolkata and headed to north Bengal’s Siliguri. The agrarian revolt that flared up in nearby Naxalbari in 1967 drew Byapari like a moth to the Naxalite movement’s egalitarian dream. “We were trained in handling pipeguns and minor weapons. Our enemies were small industrialists and businessmen,” he says of the time when he returned to Kolkata in 1970. “One day, a childhood friend, who was a CPM worker, was killed by Naxals. I saw his body and became disillusioned. Instead of reaching the capitalists, we were killing our own poor people and home guards,” he sayS.

One man’s experience in one house that he writes as fiction of the most sensational types is now an anathema to an entire community and justifies more jihadi rage. Keep going down this path folks, what can go wrong. Stupid is as stupid does. I guess that sums up the people who are consumed with this much hate.