Lucknow: On 15 August this year, when India celebrated 77th Independence Day, Uttar Pradesh Police’s Anti-Terrorism Squad (ATS) arrested five people for their alleged involvement in trying to revive the Maoist movement in the state.

What followed was a series of raids that the National Investigation Agency (NIA) — the federal agency that’s mandated to probe terror-related crimes in India — described as a crackdown on the banned Communist Party of India (Maoist).

The sites raided included the residences of two women student leaders in Varanasi and three activists from the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) in Prayagraj. Critics of the BJP dispensation, however, call it an attempt to curb dissent.

According to serving and retired IPS officers who have monitored the Maoist movement closely in Uttar Pradesh, the insurgency finds very little support today. But in the 90s — a time when it was gaining strength in several parts of the country — the movement had made significant inroads in the deeply caste-ridden state.

It was the state’s pragmatic approach and “iron hand” that helped stomp out the movement, they say.

ThePrint tracks the rise and fall of the Maoist insurgency in the country’s most populous state and what is happening here right now.

Also Read: Face of protest at BHU, ‘hardcore’ Bhagat Singh disciple — meet Akanksha Azad, now in NIA crosshairs

The beginning — ‘influx from neighbouring states’

The Maoist insurgency in India has its roots in the Naxalbari uprising — an armed peasant uprising that began in West Bengal’s Naxalbari in 1967. According to former Uttar Pradesh Director General of Police Sulkhan Singh, by the 90s, the movement had gained ground in UP’s southern, central and eastern districts.

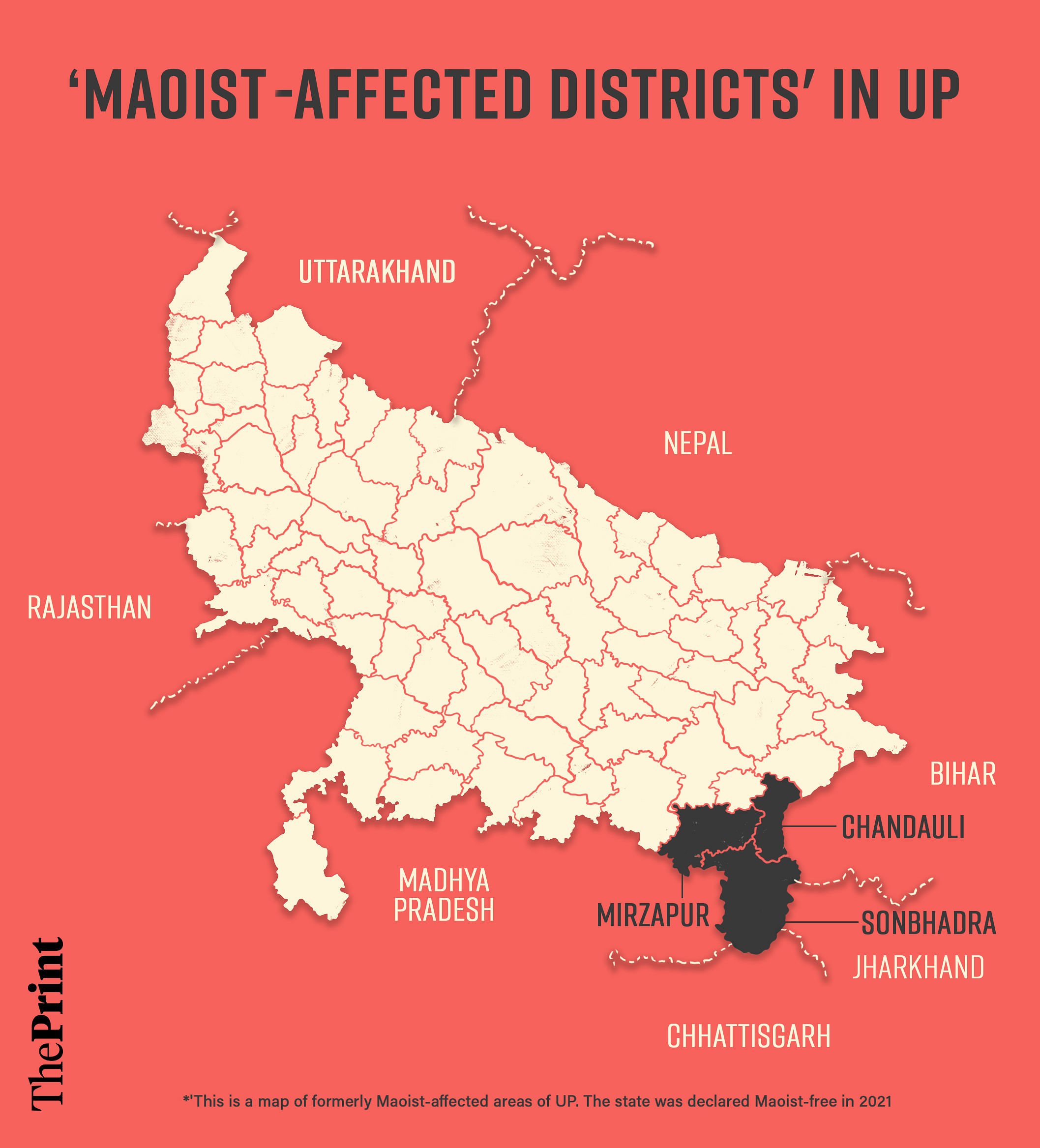

This was especially true for the areas bordering Bihar, the present-day Jharkhand and the present-day Chhattisgarh, where the insurgency was and still is strong.

“Sonbhadra, Mirzapur, Chandauli, Ghazipur, Ballia, Deoria, Kushinagar, Maharajganj and Gorakhpur were all part of a Red Corridor that extended all the way to Nepal,” Sulkhan Singh, a Uttar Pradesh-cadre IPS officer of the 1980 batch, told ThePrint.

Located in the eastern, central, and southern parts of India, the Red Corridor, also known as the Red Zone, is a region most affected by the Maoist insurgency. Although insurgency picked up in the 90s, Maoist violence had been reported in the state as early as the 60s.

In his 2012 report written for Joint Special Operations University (JSOU), former Uttar Pradesh DGP and ex-chief of the Border Security Force (BSF) Prakash Singh mentions some Maoist “turbulence” at Palia in Lakhimpur district in the 60s. JSOU is an institution under the US Department of Defense offering training for strategic and operational challenges.

Singh’s report, titled ‘Irregular Warfare: The Maoist Challenge To India’s Internal Security’, speaks about a “number of violent incidents” in the area led by Maoist leader Vishwanath Tewari.

With a huge forest cover, Palia was inhabited by the tribal Tharu community. “The state government encouraged peasants from other areas, especially eastern UP, to come to Palia, clear the forests, and undertake cultivation,” the ex-DGP, who’s credited with catalysing landmark police reforms in India, writes in the report.

These people, some of whom were rich and influential, forcibly occupied big chunks of land and ejected members of the tribes from their land, the report says.

“The Naxalites exploited their grievance,” he writes, adding that eventually, the police “snuffed out the movement”.

There were also stray incidents of violence in other districts such as Kanpur, Unnao, Hardoi, Farrukhabad, Bareilly, Moradabad, Bahraich, Varanasi and Azamgarh, the report says.

Despite this, however, it wasn’t until the year 2000 that UP’s first Maoist-related FIR was registered. By then, the erstwhile Maoist Communist Centre (MCC) had become active in the state, setting up the Dakshin Purvanchal Sangathanik Sub-Zonal Committee in south UP and later branching out into other local and area committees.

One of the largest two armed Maoist groups in India, the MCC merged with the People’s War Group in September 2004 to form the Communist Party of India (Maoist).

In October 2000, Maoists allegedly abducted and killed a station house officer and a constable in Sonbhadra. Soon, other incidents followed. In 2001, the banned MCC was accused of raiding a Provincial Armed Constabulary (PAC) camp in Mirzapur’s Khoradih and taking away a cache of arms, including 14 Self-Loading Rifles and a Sten gun.

In 2002, former prime minister Chandra Shekhar wrote to the then Union home minister L.K. Advani about the influx of Maoists from Bihar in three districts of eastern UP — Sonbhadra, Mirzapur, and Chandauli.

Sonbhadra is flanked by Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Madhya Pradesh. Meanwhile, Mirzapur shares its borders with MP, and Chandauli with Bihar.

In 2003, Saran Shah, the erstwhile king of Vijayagarh and a recipient of Padma Bhushan — one of India’s highest civilian awards — was shot dead by the insurgents.

In 2004, a landmine suspected to be planted by the Maoists blew up a truck carrying police and PAC personnel in Hinaut Ghat, Naugarh. It served as a wake up call to the state government, which then adopted a two-pronged approach to deal with the growing insurgency: police action coupled with development of the state’s most backward areas.

All three districts — Mirzapur, Sonbhadra and Chandauli — were declared Maoist-affected.

Links in ordnance factory, exploiting caste fault lines

According to ex-DGP Sulkhan Singh, the insurgents would target police, landlords and contractors with the explicit purpose of extortion.

“Gradually, they were engaged in arms loot, extortion from contractors, kidnappings, etc,” says Singh, who was posted as the Mirzapur deputy inspector general in late 1990s. “Chandauli’s Naugarh and Sahabganj had become their strongholds. But police came down hard on them and several were killed. (Eventually), Kanpur became their base, and they paralysed the industry and institutions in that area.”

A senior UP police officer told ThePrint that the Maoists established connections not only with workers at Kanpur’s ordnance factory but also with Meerut’s arms dealers in order to procure ammunition.

“They would bribe the lower officers of the ordnance factory in Kanpur and had developed a network of associates there. The bribed armourers would sell arms to Maoists groups,” he said.

Uttar Pradesh’s deeply entrenched castesim came handy to help spread the movement, according to a senior police officer quoted earlier. Ironically, for a movement seemingly against India’s castesim, its leadership positions were mostly taken up by upper-caste leaders, leaving its rank and file to be filled up by the lower castes, the officer said.

The plan, he said, was to strengthen their hold all the way to Nepal.

“They had especially influenced the Pasi community (a Dalit caste group), which is present in huge numbers in several districts of central and eastern UP. With rampant corruption in bureaucracy, they used the oppressed groups’ grievances to influence them against the government,” the officer said.

Although the Maoist groups initially got help from Nepal’s Communists, this stopped soon after the latter’s rise to power in the late 2000s, said Sulkhan Singh.

“A crackdown by Indian security forces and the local police followed and their backbone was broken, especially after 15 of them were gunned down in an encounter in Mirzapur’s Marihan police station in 2001,” the former DGP said, referring to a gun battle in Bhawanipur village on 9 March, 2001.

Five Maoists leaders were among those reportedly killed in the encounter.

Also Read: Political murders or Maoist ‘desperation’? What’s behind killings of 3 BJP workers in Chhattisgarh

Symbolism, but no widespread political support

Despite presence in UP, the Maoist movement’s spread was limited. This, according to ex-DGP Sulkhan Singh, is because it didn’t enjoy widespread support.

“The Maoists enjoyed symbolic support from some UP politicians in Bundelkhand, but it was limited and most governments, especially the Mayawati government and the BJP governments, came down hard on them,” he said.

In 2010, acting on the inputs of state intelligence, Mayawati, the then chief minister, declared 761 villages in Sonbhadra, Mirzapur and Chandauli — UP’s three most Maoist-affected districts — as Ambedkar Grams.

After bringing these villages under the Ambedkar Gram Vikas Yojana, she ordered electrification and improvement of healthcare, drinking water facilities, and the public distribution system.

The idea, according to another senior UP police officer, was to accelerate development in these areas to check the spread of the Maoist ideology. “Since the BSP’s votebank mainly comprised the population (Dalits) that was being influenced by Maoist ideology, she came hard on them,” the officer told ThePrint.

Also part of the strategy was to train the state police in combat. As a result, Mayawati sent batches to Chhattisgarh to train in jungle warfare. The PAC got training from the Greyhounds — a special police unit trained in counter insurgency in the then undivided Andhra Pradesh.

Police also began imparting training to the youth in these districts as drivers and computer operators, with several of them eventually absorbed by security and intelligence organisations.

“The deployment of PAC and training of police helped curb the growth of Maoist activity in UP,” Additional Director General of Police (Special Task Force) Amitabh Yash told ThePrint.

But it wasn’t just the Mayawati government that acted tough on the insurgents. Speaking at an event in 2014, Rajnath Singh, the then Union home minister, said when he was the chief minister between 2000 and 2002, he assured “police forces freedom from hassle by (the) Human Rights Commission” while “tackling the Maoist threat”.

All these efforts helped arrest the movement in the state. In 2021, the Ministry of Home Affairs declared the state of Uttar Pradesh “Maoist-free”.

Curb on Maoists, or crackdown on dissent?

In its statement after last month’s crackdown, the NIA said there were “attempts by frontal organisations and student wings to motivate/recruit cadres of the CPI (Maoist)”.

The crackdown came on the heels of a significant arrest in Bihar a week earlier. On 10 August, Bihar Police arrested Pramod Mishra, a CPI (Maoist) politburo member wanted for his alleged involvement in the 2021 Dumaria massacre — a case in which four of a family were killed and hanged to avenge the deaths of four Maoists.

In its statement, the NIA said in a previous FIR, it named several suspects, including Manish Azad and Ritesh Vidyarthi, along with their associates Vishwa Vijay and his wife Seema Azad, Manish’s wife Amita Shireen, Kripa Shankar, Soni Azad, Akanksha Sharma and Rajesh Azad (Rajesh Chauhan) as key figures trying to revive the CPI (Maoist) in the state.

Rajesh Chauhan has reportedly been actively protesting against the expansion of Manduri airport expansion in Azamgarh’s Khiriyabagh. He’s also believed to be associated with the Sanyukta Kisan Morcha (SKM) — the farmers’ organisation that was leading the protests against the Narendra Modi government’s now repealed farm laws.

Akanksha, meanwhile, is an office-bearer of the Bhagat Singh Chhatra Morcha (BSM) — a student outfit that has been leading protests on several issues, including reservation for OBC students in hostels.

Also raided were two members of the Janvadi Party (Socialist), a party that allied with the Samajwadi Party in the 2022 Uttar Pradesh election.

The police action has drawn a backlash in the state, with Left groups and social activists calling it a suppression of dissent.

Manish Sharma, convener of the Varanasi-based political outfit Communist Front, claims the insurgency was put out in UP since the government crackdown in the 90s.

“Their activity is virtually absent, although we can’t say what’s happening inside the organisation,” he said. “Even Maoist sympathisers say that their hold is over. Right now, all those working for the cause of adivasis, student issues, (now-abolished) farm laws and those who critically analyse the government’s functioning are being branded as Naxalites.”

There’s a narrative being built against activists and “the government wants to ensure that they are sidelined”, he said. The attempt, Sharma said, is to ensure that the general public stays away from anyone advocating for the cause of adivasis, minorities and students.

“I, too, was picked up by the UP ATS on 15 May and grilled for days before I was let off,” he said. “Whenever agencies like the NIA and ATS are involved, the general public thinks that there is something serious. But they (the government) are unable to give any evidence linking those targeted by raids with any violent activity.”

(Edited by Uttara Ramaswasmy)

Also Read: Chhattisgarh Maoists suffering from betrayal, fewer leaders and weapons, and too many roads