The French poster.

Livorno, Italy. Night. Mario, a lonely, young employee, during its wandering accidentally meets a girl. She’s blonde, a stranger, and the two make acquaintance. Despite Mario begins to fall in love with Natalia (that’s Maria Schell’s character’s name), she confesses him she has a lover, a man who, after leaving her, has promised to come back to take her away with him. Mario doesn’t believe the return of the man and he and Natalia every night meet to speak and walk along the streets of the city. As the man doesn’t appear, night after night the two seem ever more bound together and finally, just when Natalia seems decided to stop her waiting and to accept the love of Mario, suddenly the man appears. Natalia run to embrace and kiss him and the two go away. Mario, a lonely man too, resumes his wandering along the streets of Livorno.

“Le notti bianche” (“White Nights”; Luchino Visconti, 1957) is an ambitious and someway elusive movie. Adapted by the Dostoevskij novel of the same name (that later inspired also “Quatre nuits d'un rêveur”, Robert Bresson, 1971) the film is set entirely in a some “city of Livorno” (replacing St. Petersburg) that was completely re-built in the Roman studios of Cinecittà.

When I first watched this enigmatic movie (I was young, then) I was considerably disappointed by a movie that (I judged) relied on a minimal story, lacked of action and was weighted by too much words. Reviewing the movie some weeks ago I found in its some undoubt values that have much changed my first judgement; technically “Le notti bianche” has a marvelous (and prized) scenography centered on the artistic reconstruction of an imaginary city (a foggy, nocturnal, surreal, magic, aethereal Livorno) that acts as a “soul’s place”: the fantastic frame giving substance to a dream. The second thing resides in the faboulous performance of Marcello Mastroianni, the great versatile actor here at the very best (that is my firm conviction) of his outstanding career. And the story itself is extra-ordinary (meaning: not easy referable to known schemes) as Visconti (with Dostoevskij) speaks here of a hidden side of Love: its potential “absurdity” displayed in the illusion of a man who tries to defeat his loneliness only by the purity of his feeling (obviously, and sadly, a not sufficient condition).

Note: in a little role (a prostitute) there is Clara Calamai, a legendary presence in Italian cinema: hers the first nude in “La cena delle beffe”, hers the first Italian neo-realist femme fatale in “Ossessione”.

r.m.

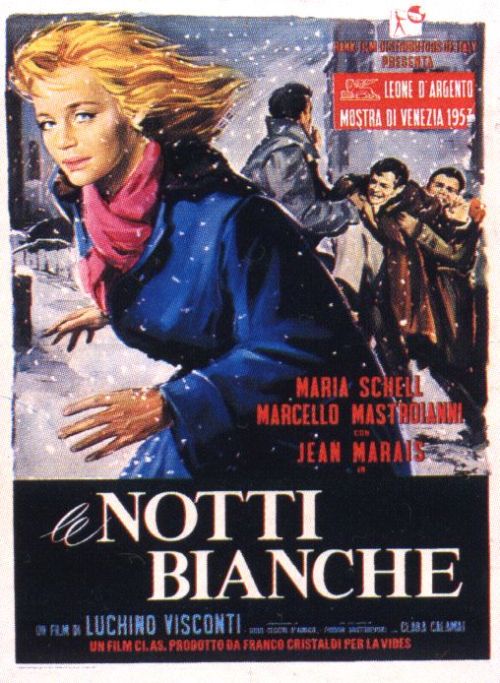

The Italian poster.

Two in the night (Marcello Mastroianni and Maria Schell)

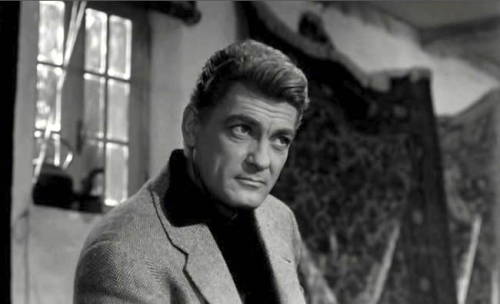

Jean Marais

Mario (Marcello Mastroianni)

Natalia and Mario

Natalia and Mario

In the snow.

Her true love.

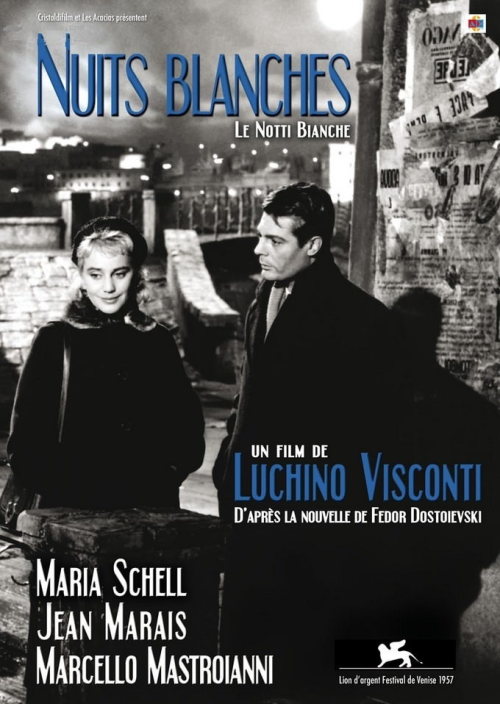

Alternative French poster.