The Disney+ movie Togo is about the heroic run of the titular Siberian husky, who led a team of sled dogs across hundreds of miles to deliver diphtheria antitoxin to the town of Nome, Alaska, during an outbreak of the disease in 1925. Directed by Ericson Core, with a Writers Guild Award–nominated script by Tom Flynn, Togo is based on the events of what become known as the “Great Race of Mercy,” or the “1925 serum run to Nome.” Scenes from the run are interspersed with flashbacks to Togo’s origin story, showing him making repeated escapes from the kennel of musher Leonhard Seppala (Willem Dafoe).

The title card at the beginning declares that Togo is based on a true story, but how much of this is hard history and how much is Disney magic? Was Togo really such a good boy as the movie suggests? We consulted cousins Gay Salisbury and Laney Salisbury’s deeply researched book about the serum race, The Cruelest Miles: The Heroic Story of Dogs and Men in a Race Against an Epidemic, along with what few other sources we could find, to break it all down below.

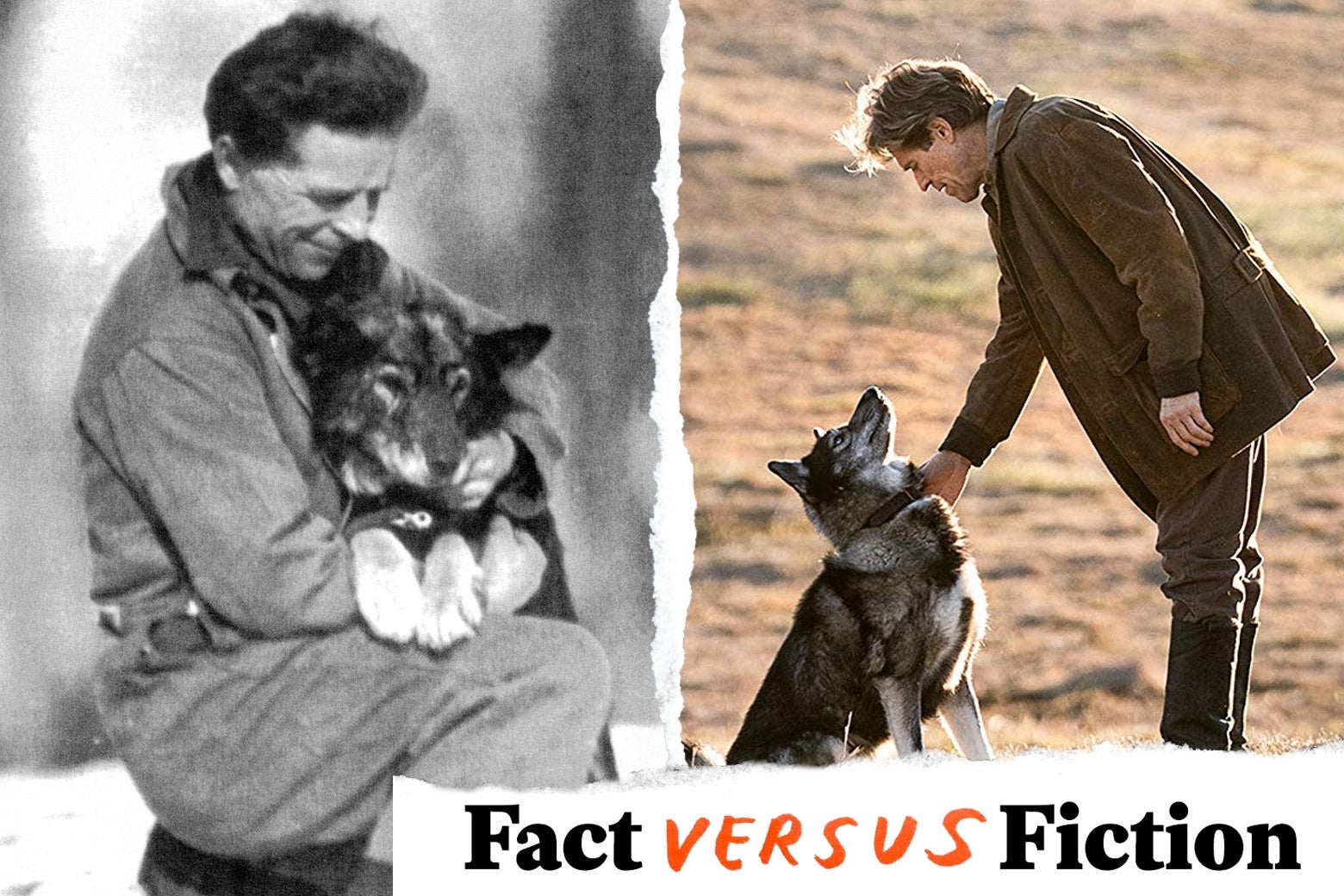

Togo

In Disney’s telling, Togo’s beginnings are an underdog story. As a puppy, he is a runt with little more than a fighting spirit and the endorsement of Seppala’s wife, Constance (Julianne Nicholson). Seppala grumbles that Constance is too softhearted and hints that a bullet might have been the easiest solution to Togo’s behavioral issues. And Togo has many behavioral issues: He’s magnetically drawn to Seppala, such that he successfully defies any of Seppala’s attempts to pen him up or give him up for adoption. Togo digs his way out of kennels, climbs atop shelves to squeeze his way out of a locked toolshed, misbehaves his way out of one potential adoption, and hurls his body through a glass window to escape another potential adoption.

According to The Cruelest Miles, although Togo was the only puppy in his litter, he was indeed smaller than average, and worse, he had a painful condition that made his throat swell. The Salisburys also write that Togo was indeed “difficult and mischievous,” as well as resistant to being locked up. He once attempted to leap over a 7-foot-high fence and got stuck in the wiring. He was disruptive to harnessed sled dogs, just as he’s shown to be in the film. Finally, Seppala did indeed attempt to give Togo away to a woman who tried to make him a house pet, and according to The Cruelest Miles, Togo really did escape by jumping through a windowpane.

In the movie, Togo gets his first break by busting loose and harassing Seppala’s harnessed team until Seppala finally gives him a chance run with the big dogs. By the time Seppala arrives at home, Togo has been moved to the lead position, and Seppala is marveling at Togo’s speed. According to the Salisburys, this is also true to life. The real-life Seppala was “astounded” at the effect of the harness: The 8-month-old Togo went from pesky to serious, and Seppala “finally understood what Togo had been wanting all these months: to be a member of the team.” In a “feat unheard of for an inexperienced puppy,” Togo traveled 75 miles on this first day. Seppala described him as an “infant prodigy” and a “natural-born leader.”

The dog that plays the adult Togo in the movie is a so-called Seppala Siberian named Diesel (the “Seppala Siberian” is now its own breed) and is actually Togo’s great-grandson, “14 generations removed,” according to the movie’s director. Not only is Diesel related to Togo, he also resembles Togo in coloring: Unlike many Siberians, Togo had a darker coat. It’s worth mentioning that Togo’s own lineage wasn’t too shabby: His father was Suggen, who had led Seppala’s team to victory in the 1914 All Alaska Sweepstakes race.

The Diphtheria Outbreak

At the start of Togo, Seppala arrives in town after a run to find that a diphtheria outbreak has already claimed the lives of five children. Mayor George Maynard (Christopher Heyerdahl), who is also the publisher of local newspaper the Nome Nugget, and the town doctor, Curtis Welch (Richard Dormer), gather the important-looking men of the town in a saloon. Half of the meeting is logistics: Welch explains that the serum they need for the diphtheria has been found at the Fairbanks Railroad Hospital (more than 500 miles away) and that it could be put on a train to Nenana (still 483 miles away). Maynard is all in favor of getting the diphtheria antitoxin flown in by airplane, weather notwithstanding. The other half of the meeting is not-so-subtle pressure on Seppala to ride to Nenana to pick up the serum. Seppala is initially unmoved, but after peeking into the windows of the town hospital and seeing children crying and coughing, he is convinced he must go, despite the misgivings of his wife.

In real life, things played out a bit differently. Welch and Maynard were present at the equivalent meeting, but Seppala was not present nor very much involved in the decision. Still, his reputation was perhaps even greater than the movie suggested: According to The Cruelest Miles, he was known as the “fastest musher in Alaska,” and his nickname was the “King of the Trail.” It was Seppala’s boss at the Hammon Consolidated Gold Fields Company, Mark Summers, who came up with the plan to use two teams of dogs, traveling toward each other from Nenana and Nome to meet at the halfway point in Nulato. Summers is also the man who recommended Seppala for the run. He told Seppala that the ad hoc health board “believed that Nome’s fate lay in Seppala’s hands.”

And while, in the movie, Constance Seppala initially objects to her husband’s participation, saying that the town should “pick someone with more stake in [the diphtheria outbreak],” in reality the Seppalas did have more of a stake than is indicated by the film script: They had an 8-year-old daughter named Sigrid.

The Great Serum Race

In the movie, Seppala sets out for Nenana in the midst of a blizzard. In reality, the winds were in a “rare state of calm,” and Seppala had a crowd to cheer on the beginning of his journey to Nulato—halfway to Nome, but still a six-day journey encompassing a total of 630 miles. As shown in the movie, more teams were added to the relay mid-run, and so Seppala ended up traveling a total of 261 miles (170 miles to pick up the serum and 91 miles with the serum)—still an enormous distance. Despite the differences in the Disney version of the story—such as the blizzard at the beginning—the fictionalized aspects are not an exaggeration of the dangers involved. “The trail between Nulato and Nome was one of Alaska’s most hazardous,” with most of it running along “the windswept, blizzard-prone coast of Norton Sound,” known to Alaskans as “the ice factory,” write the authors of The Cruelest Miles. The most dangerous part of this trail was the 42-mile shortcut across the sound. The safer alternative was twice as far. Beyond the possibility of getting caught in a storm or a dog injuring its paw on a shard of ice, it was also likely that the ice of the Norton Sound could break up and carry the team out to sea. It had happened to others.

One of the most terrifying moments in the movie is the second crossing of the Norton Sound, on the way back toward Nome with the serum. Seppala and his team are crossing the sound when they find themselves stranded on an ice floe, separated from shore by a narrow but formidable strip of sea. Seppala tosses Togo ashore, and the dog somehow manages to tow the floe close enough to the coast to enable the rest of the team to follow.

This is very close to what Seppala told the Boston Sunday Post really happened, albeit not on this particular run but on a previous trip. And while the suspense in the movie is more than adequate, Seppala described even more danger. In Seppala’s account, as summarized in The Cruelest Miles, the tow rope connecting Togo and the rest of the team on the floe snapped, and the end of the rope fell into the water. Togo jumped into the water, clambered back out, wrapped the rope around his body, and pulled.

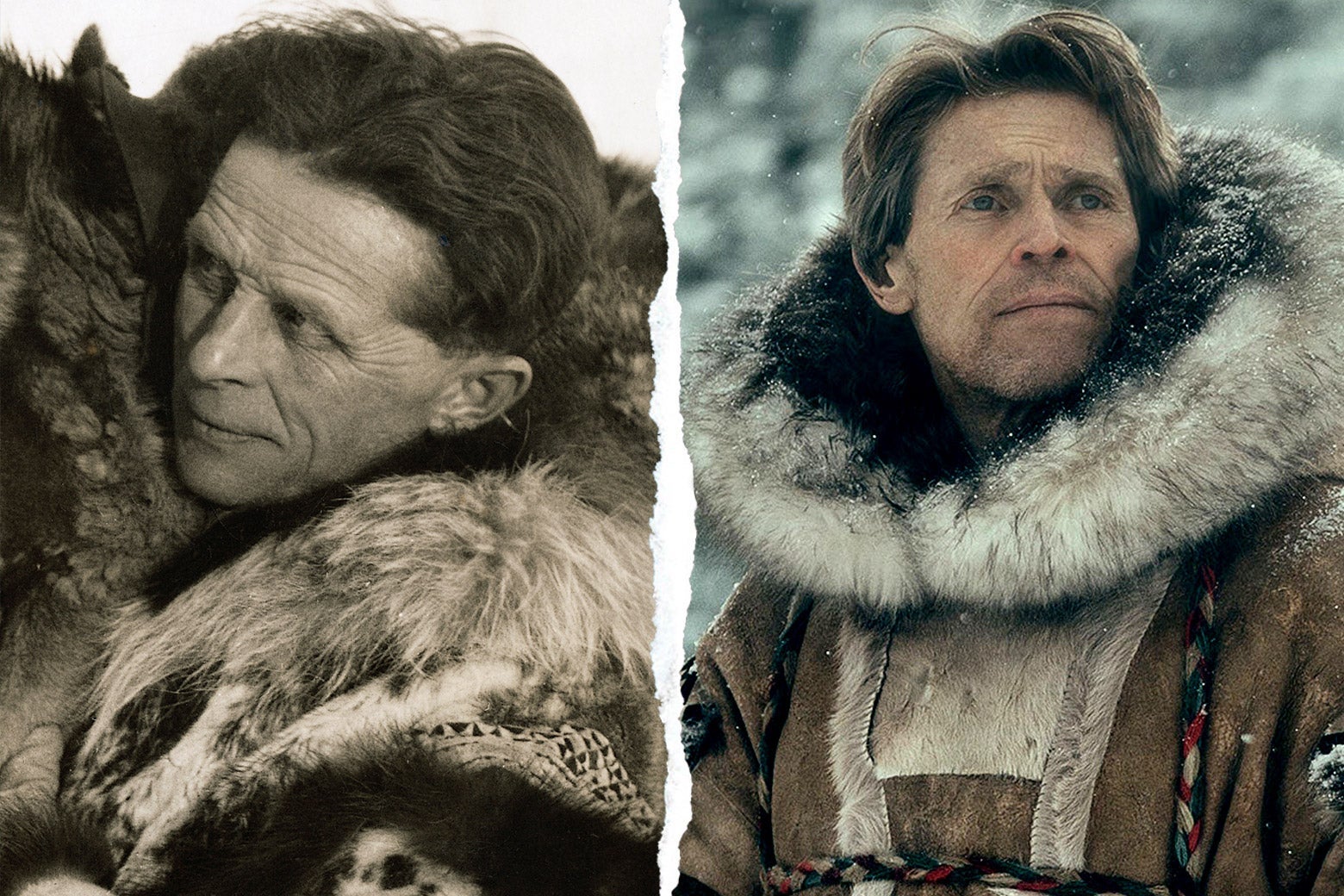

Leonhard Seppala

In the movie, Leonhard Seppala is depicted as a stoic, hardscrabble Norwegian whose demeanor is in direct contrast to that of his softhearted Belgian wife. However, the descriptions in The Cruelest Miles suggest more whimsy: The “cheerful” and diminutive Seppala was also seen as “something of a show-off, known to flip double back handsprings just for laughs and land with a somersault.” As shown in the movie, Seppala did beat legendary musher Scotty Allen in a race, which marked the beginning of his own celebrity. One competitor described his communion with dogs as “unnatural control” or “hypnotism.”

The mutual trust between Seppala and Togo was also as depicted. Togo was Seppala’s favorite, and the musher often depended on Togo’s instincts and sense of smell when his own vision failed him.

Balto

Balto makes a brief cameo in the movie: He’s the lead dog in Gunnar Kaasen’s team. Because Kaasen is the one who actually delivers the serum to Nome, he is the one who receives the lion’s share of the glory. While certain details have been changed, this is largely what happened, and explains the disproportionate fame that the real-life Balto has enjoyed; beyond the media attention, there were movie deals, a tour, and a statue.

None of this is to say that Balto deserved no credit: Kaasen’s team had to drive through a blinding blizzard, and according to The Cruelest Miles, Balto’s senses of smell and touch were what kept the team on the trail. And although Seppala did not seem upset on his own account (he praised Kaasen), he was reportedly upset that Togo had not received his due. According to The Cruelest Miles, Seppala wrote: “I hope I shall never be the man to take away credit from any dog or driver who participated in that run. We all did our best. But when the country was roused to enthusiasm over the serum run driver, I resented the statue to Balto, for if any dog deserved special mention it was Togo.”

On the topic of unsung heroes, The Cruelest Miles also notes the deficient coverage on the contribution of the Native drivers—“who covered nearly two thirds of the run” but were not as interesting to movie producers or reporters. As the Salisburys put it, they were “considered a part of the landscape.”

Togo’s and Seppala’s Deaths

The movie leaves out several details about Togo’s death. By January 1927, Seppala had opened a kennel with a socialite named Elizabeth Ricker in Poland Springs, Maine, and he was traveling between Alaska and Maine. He made the decision to leave Togo behind in Maine in March 1927, concerned that the journey would be too much for the retired dog. And while the movie Seppala gets the date of Togo’s death right (“He left us on a Thursday in December”), in reality Seppala decided to put Togo to sleep, given Togo’s joint pain and partial blindness.

As for Seppala, he lived to be 89. “While my trail has been rough at times,” he wrote in his diary at age 81, “the end of the course seems pretty smooth, with downhill going and a warm roadhouse in sight. And when I come to the end of the rail, I feel that along with my many friends, Togo will be waiting and I know that everything will be all right.”