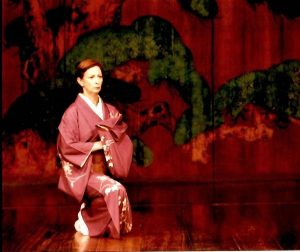

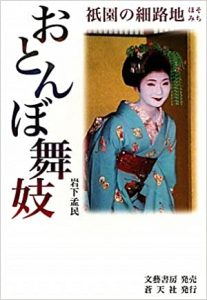

The Kimono Tattoo, a fast-paced mystery set in Kyoto, follows American translator Ruth Bennett on her dangerous quest for the truth. Ruth’s expertise in kimono history and fluency in Japanese give her the tools. Her intrepid friends take risks to help. Amid the chaos, Ruth’s practice of Nihon buyō (Japanese dance) steadies her.

As we explored in our last blog, The Kimono Tattoo gives insight into the practice of Nihon buyō by its teachers and students.

Meet Rebecca Copeland

Today’s blog features a special treat. We get to catch up with the author, Rebecca Copeland. Renown for her expertise in modern Japanese women’s literature, Rebecca has studied dance in Japan, too. Our interview explores how her experiences learning Nihon buyō shaped the dance scenes in The Kimono Tattoo.

Today’s blog features a special treat. We get to catch up with the author, Rebecca Copeland. Renown for her expertise in modern Japanese women’s literature, Rebecca has studied dance in Japan, too. Our interview explores how her experiences learning Nihon buyō shaped the dance scenes in The Kimono Tattoo.

You can also hear Rebecca’s podcast on The Kimono Tattoo. It’s on the popular channel, Japan Station: A Podcast About Japan by JapanKyo.com

The fun of taking first steps in Nihon buyō

JB: Great to talk with you today, Rebecca. Let’s start with your first experiences of Japanese dance.

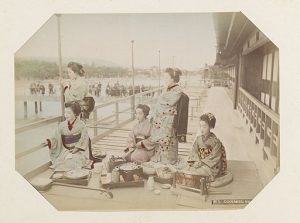

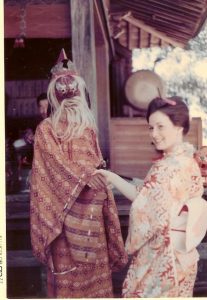

In your blog post on dance, you recount taking your first steps in dance in 1976 at age nineteen. You describe the fun of staying “for tea, sweets, and gossip” after the lesson. Much later, rather like Ruth, you took Nihon buyō lessons as an adult in Kyoto. But what were those first lessons like?

RC: Thanks, Jan. I first began studying Japanese dance when I was a college student in Japan. A young woman about my age offered to teach dance to the foreigners where she lived in Fukuoka. At the time I did not know how extraordinary this was. I’ve since learned how difficult it is to acquire the credentials and more importantly the permission to teach a traditional art. But since this young woman was only providing foreigners with a form of “art appreciation,” her sensei thought it would be okay. After all, no one expected any of us to pursue dance seriously.

RC: Thanks, Jan. I first began studying Japanese dance when I was a college student in Japan. A young woman about my age offered to teach dance to the foreigners where she lived in Fukuoka. At the time I did not know how extraordinary this was. I’ve since learned how difficult it is to acquire the credentials and more importantly the permission to teach a traditional art. But since this young woman was only providing foreigners with a form of “art appreciation,” her sensei thought it would be okay. After all, no one expected any of us to pursue dance seriously.

What stands out about these early dance lessons? What did you learn?

RC: For me, it was much more than “art appreciation,” and even much more than dance. I learned basic forms of etiquette. I learned different ways to understand grace and elegance. I learned how to dress myself in a kimono and how to fold and store the kimono after use.

RC: For me, it was much more than “art appreciation,” and even much more than dance. I learned basic forms of etiquette. I learned different ways to understand grace and elegance. I learned how to dress myself in a kimono and how to fold and store the kimono after use.

Even though my sensei knew I would never excel at the form, she still pursued her teaching with serious intention. She was proud of her art. It meant so much to her. Clearly, it wasn’t just a hobby or a weekend exercise. It was a way of life. Her investment in her art touched me deeply. This experience, along with others I had that year in Fukuoka, influenced me to continue my study of Japan.

Now I see why Ruth Bennett knows so much about kimono. What about your later dance lessons as an adult?

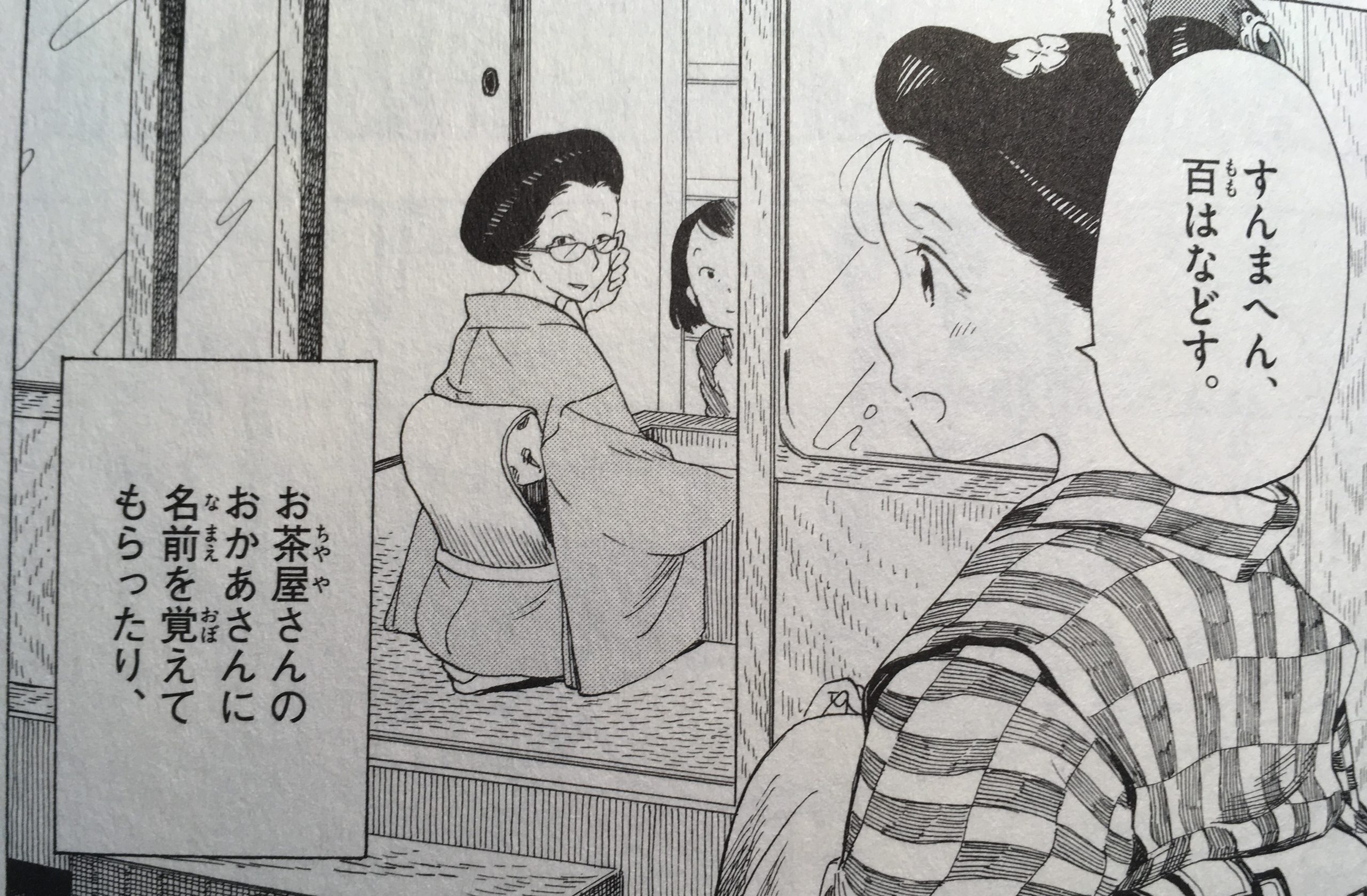

In the mid-2000s, I lived for a year in Kyoto. I taught at what was then the Kyoto Center for Japanese Studies (a consortium of American universities). The students in my program were given the opportunity to study Japanese dance, but none of them did. I asked the organizers if I could.

The class was offered by Nishikawa Senrei Sensei, of the Nishikawa School of Dance. All the other students in the class were about the age I was when I first began studying dance in Fukuoka.

The class was offered by Nishikawa Senrei Sensei, of the Nishikawa School of Dance. All the other students in the class were about the age I was when I first began studying dance in Fukuoka.

We began our studies with the same dance I had learned when I was 19, “Sakura, sakura.” But because in Fukuoka I had trained in the Hanayagi-style, the movements were different.

That must have been frustrating. Like Ruth Bennett, you had to start all over again.

Yes, I do remember feeling very frustrated at first. I knew I should know this. But everything was new to me, and I felt so disoriented.

Actually, it had been that way from the start. As soon as I arrived in Kyoto, I felt dislocated. I was used to Tokyo. After that year in Fukuoka, my next visits to Japan had all been in Tokyo. I had lived there off and on for close to ten years. Kyoto was so different. I found it hard to get around as I was unfamiliar with the bus system (in Tokyo I almost always took trains.) Everything was different.

On top of that, I was in a class with quick young women who immediately picked up the dance movements. I was always the one lagging behind. But Senrei Sensei was very kind to me. After class I would often linger and talk with her about literature. That’s when I learned that sensei also choreographed new, original dances. She performed one that year based on the French sculptor Camille Claudel. Another dance of hers retold the famous Meiji-era story of Mori Ogai’s “Dancing Girl” (Maihime).

Senrei Sensei was incredibly talented. She invested her time teaching foreigners out of a spirit of generosity and passion, not unlike that of my first dance teacher.

Senrei Sensei must have been quite a talented artist in her own right.

Absolutely. Senrei Sensei managed her own studio, curated her own recitals, choreographed her own dances, and traveled the world. She was grounded in traditional Japanese arts and amazingly independent and fierce. Jonah Salz published a wonderful essay about Senrei Sensei in Kyoto Journal.

She was a strict teacher. A sharp glance from her would be enough to make me wilt with embarrassment and regret. But she was also patient and understanding. I would be so honored to share The Kimono Tattoo with her, but she tragically died several years ago.

Such rich experiences! How did these help you craft the dance scenes in The Kimono Tattoo?

Admittedly, the dance teacher is loosely modeled on Senrei Sensei. She taught me so much about Kyoto and kimono. She also taught me about art and about finding the source of art in yourself.

As I noted, I wasn’t very quick to pick up the steps and I often felt like a drag on the class. As we prepared for our recital, I was amazed by how smooth the young women in the class were. They had no problem remembering all the steps.

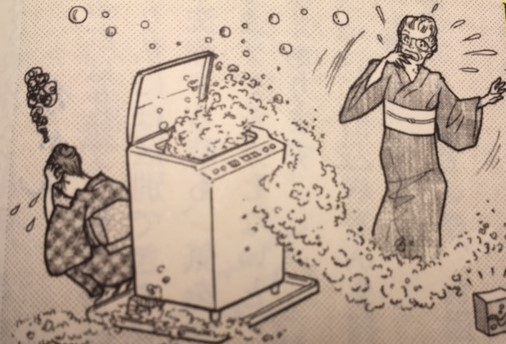

Later, after one class when we were putting away our kimono, one of the students told me that they watched videos of earlier performances. They received them from previous students. Aha! I could certainly use that help. I wanted to see those videos and practice at home with them, too.

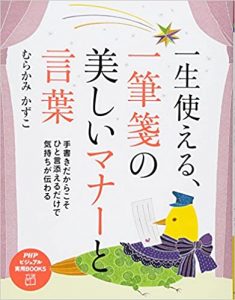

When I mentioned borrowing a video to Sensei, she grew visibly irritated. “Art is not about perfecting form!” she snapped. “It’s not just about memorizing. You have to feel it in your heart.” Then and there, she forbade all of us from studying the videos. She told me to listen to the music at home. “Feel the music,” she said as she thumped my breast. “Feel it here.” So, I tried that. I was never as smooth as the other students, but Sensei complimented me for having the right spirit. I think Ruth and her sensei share a similar relationship. Ruth isn’t perfect but she is keen to appreciate the spirit of the dance.

Looking back on these dance lessons, what did you take away from the Sensei’s guidance?

Strangely, I think her lessons helped me in other aspects of my life as well. I stopped worrying so much about making mistakes and getting facts wrong in my own lectures and classes. My classes became better as a result. And, perhaps it is this awareness of following the heart, trusting the heart, that gave me the courage to try my hand at a novel.

Do you have more in store for these characters?

Rebecca, I enjoyed the lively cast of characters in The Kimono Tattoo. My favorite is Ruth’s pal Maho, who wears a Mohawk. And, of course, one gets attached to Ruth Bennett, who can’t pull away from signs of danger. What’s next for them?

Thanks, Jan. You know, it took so long to complete The Kimono Tattoo–almost ten years. I started it in 2012, and I could only work on it during the summers. That means that I have lived with Ruth and Maho for a long time. They continue to visit me, especially when I return to Japan. Ruth will walk alongside me and make comments. I don’t think I’ve seen the last of her.

Will the next mystery take place in Kyoto, too?

Yes. A few years ago I started another Ruth Bennett story. This one is set in the Nishijin area of Kyoto. It features the sumptuous brocade for which Kyoto is famous.

Nishijin brocades are exquisite. But like so many works of art that rely on human labor, the people who enjoy the brocades and the people who labor to produce them live very different kinds of lives. In earlier times weavers often lived subsistence lives and were exploited for their labor. This kind of dichotomy, the bright side versus the darker underside, as in The Kimono Tattoo, fascinates me. I want to see what happens when Ruth spends time with this art form. Sadly, people will die. And Ruth will find herself once more in the thick of things.

After this novel I would like to send Ruth on the road. She’ll spend time in Fukuoka and perhaps Nagasaki exploring the traditional arts there and trying to stay out of trouble. Nagasaki is a particularly interesting city with its different layers of cultural histories: Japanese, Chinese, Dutch, British, American, and more.

Thanks to Rebecca Copeland

Following Ruth Bennett to Kyushu will be an adventure for sure. And I look forward to learning more about Nishijin in her next Kyoto mystery.

Thanks for sharing your experiences with Japanese dance and photos, Rebecca. This gives me renewed appreciation for the evocative dance scenes in The Kimono Tattoo and Ruth’s brilliant sensei.

I highly recommend The Kimono Tattoo. “Silks unravels. A tattoo is forever. Layer by layer the truth is revealed.” And you can stay up all night watching the layers fall away.

Jan Bardsley, “Dance in The Kimono Tattoo: Interview with Author Rebecca Copeland.” janbardsley. web.unc.edu June 3, 2021.