- India

- International

Ex-Foreign Secretary writes: West may praise Henry Kissinger’s diplomatic triumphs but not many tears will be shed in India

Outwardly a champion of democracy and freedom, Kissinger may have cracked the Chinese regime open but deceit and perfidy marked his engagement with New Delhi

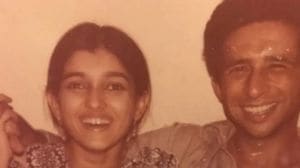

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi with US Secretary of state Henry Kissinger. She hosted lunch in his honor in New Delhi, 1974. (Express Archives)

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi with US Secretary of state Henry Kissinger. She hosted lunch in his honor in New Delhi, 1974. (Express Archives) Henry Kissinger, who served as the National Security Advisor and Secretary of State to two US Presidents — Richard M Nixon and Gerald R Ford — between 1969 and 1977, has died at the age of 100. He was regarded by the West as its most famous diplomat in the 20th century, and by China as their “friend”. Although he has been a polarising figure, he is remembered for his role in ending the two-decade-long American involvement in the Vietnam War and in the opening of relations between the United States and the People’s Republic of China. The world will shower him with praise for what Politico magazine calls his “transformative diplomatic actions”.

There is no doubt that Kissinger played a significant part in global diplomacy in the 1960s and 1970s and as a senior advisor to several presidents thereafter in interpreting world events — in particular the opaque Chinese communist regime. He was the go-to person for CEOs of global corporations, world political figures and the international media who wanted to understand how opportunities in China could be leveraged for gain. He profited handsomely from the advice he dispensed. But while the West feted him as a statesman and a strategist, his record with India is less savoury.

After the Nixon administration took office, Kissinger prioritised relations with Pakistan over India. He was instrumental in pressing for significant military and economic assistance during President Yahya Khan’s visit to Washington in October 1970. In May 1971, when India confronted its most significant national security crisis in living memory after ten million refugees from East Pakistan poured into India as a result of the atrocities by the Pakistani military, Nixon and Kissinger were more intent on securing Pakistan’s help in establishing ties with China rather than in compelling the Pakistani regime to stop the carnage at home.

Despite the widespread international reportage of the genocide, Nixon wrote to Yahya Khan on May 7, 1971, to “understand the anguish you must have felt in making the difficult decisions you have faced.” Although Kissinger had personally seen the Nazi persecution of the Jewish community in Germany, from where he finally fled in 1938, he showed neither compassion for the people of East Pakistan nor contrition for America’s unwavering support to the Pakistani regime’s activities until the bitter end.

Kissinger continually acted in a deceitful manner so far as India was concerned. In July 1971, during his visit to India on the eve of his secret visit to China, he told P N Haksar, Principal Secretary to the Prime Minister, that the US would “under any conceivable circumstances” back India against Chinese pressure. He never disclosed that he intended to visit China only days later to normalise relations. He also told External Affairs Minister Swaran Singh that the US had only “disinterested concern in the balance of national or political forces within South Asia”. In reality, he was doing everything possible to sustain the Pakistani genocide in future Bangladesh and assist Pakistan in dealing with India. When the Bangladesh crisis worsened, Kissinger advised Nixon to “introduce the question of what would happen to our (American) aid if India attacked Pakistan”, during Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s visit to Washington in November 1971, in a transparent attempt to blackmail India. When the war began, Kissinger, on the one hand, routed military equipment to Pakistan through its middle-eastern allies and on the other, suspended all economic assistance to India. His instructions were specific — a case was to be made, technically and legally, to differentiate between the aid given to India from the aid given to Pakistan.

His most perfidious actions were his efforts to put pressure on India through the Chinese. Even before the conflict started, Kissinger met the Chinese Ambassador to the United Nations, Huang Hua, on November 23, 1971, to propose that they coordinate action in the UN Security Council on the India-Pakistan issue so that the US “not move too far away from you (China) on this issue”. It was also at this meeting that Kissinger (and George H W Bush, later the President of the United States) shared the specific location of Indian military units deployed along the frontier with East Pakistan, as well as crucial information that India had diverted two mountain divisions from the China front to East Pakistan. He even offered to send further specific information “in a sealed envelope to the hotel if you want us to”. This was but a prelude to Kissinger’s subsequent actions during the Bangladesh war.

In his meeting with the Chinese on December 10, 1971, Kissinger described what was happening “in the Indian Subcontinent as a threat to all people,” and that Pakistan was being punished by India because it was a friend of China. Kissinger conveyed that “if the People’s Republic of China were to consider the situation on the Indian subcontinent a threat to its security, and if it took measures to protect its security, the US would oppose efforts of others (Soviet Union) to interfere with the People’s Republic.” It was as direct a suggestion as could possibly be made by a high-ranking political figure to the Chinese to open a third front when India was already fighting Pakistan on two fronts.

He would later tell Nixon, wrongly as it turned out, that China “might be more inclined to step up its own activities”. China had understood the game the Americans were playing and had neither the intention nor the capability to threaten India with military action. India figured in many of Kissinger’s subsequent meetings with the Chinese until he demitted office in 1977. Kissinger usually talked about India in a derogatory and patronising manner. Outwardly a champion of democracy and freedom, Kissinger in reality was instrumental in supporting an authoritarian regime against the one nation in Asia that was democratic and hewed to the values that defined the United States.

After his retirement, he built a hugely profitable consultancy practice by using his first-mover advantage with the Chinese leadership. He would visit China regularly, and help others build the connections that gave the Chinese access to much of the capital and technology for their modernisation. The Chinese well understood Kissinger’s immense value and pandered to his vanity and ego. In a sense, Kissinger was harnessed by Mao Zedong and his successors to pull the Chinese cart into the 21st century and has contributed, perhaps more than any other single individual, to helping China emerge as a true challenger to American power.

Kissinger had many undeniable achievements but let us, as Indians, not succumb to amnesia and join the others in heaping praise upon an individual who, for whatever reason, harmed India’s interests.

Gokhale was India’s Ambassador to China and retired as Foreign Secretary in 2020. He’s the author, most recently, of After Tiananmen: The Rise of China

EXPRESS OPINION

Best of Express

More Explained

May 12: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05