- India

- International

Who was Irom Sharmila: A look at the life she has lost, and memories that sustain her

Who was Irom Sharmila before her extraordinary protest against the AFSPA took over her existence? As her fast enters its 15th year, a look at the life she has lost, and the memories that sustain her.

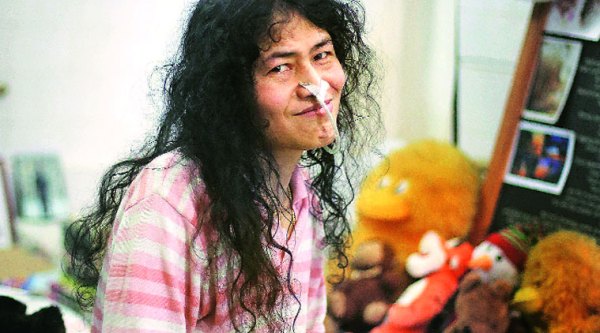

Irom Sharmila (left) cradles Thoi, a pair of guinea pigs she has adopted in confinement. (Source: Deepak Shijagurumayum)

Irom Sharmila (left) cradles Thoi, a pair of guinea pigs she has adopted in confinement. (Source: Deepak Shijagurumayum)

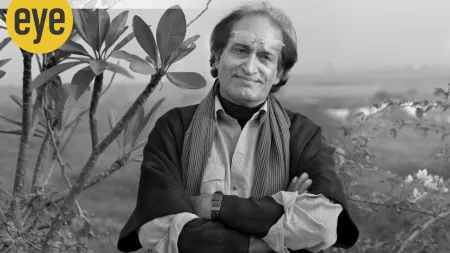

The Special Ward at the Jawaharlal Nehru Institute of Medical Sciences in Imphal, Manipur, is cut off from the swirl of chaos that is the life of a hospital. Here, in Room No. 1, 42-year-old Irom Sharmila Chanu, the most recognisable face of this conflict-ridden state in the Northeast, has lived for 14 years.

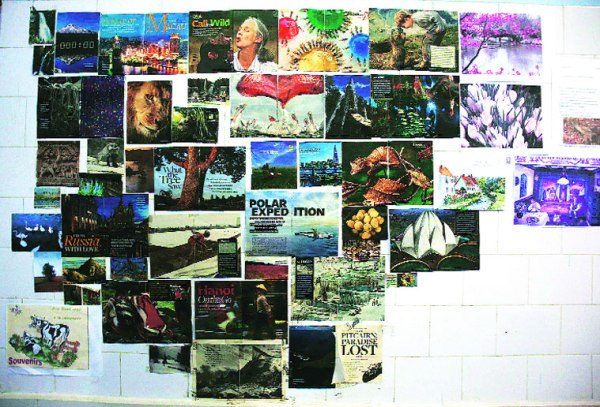

The four walls of Sharmila’s room, a bright sea-green that has paled over the years, enclose her entire world. Mementoes of her friendships and love, gifts and letters from her family and supporters, are stacked on overflowing tables, stashed in the sole cupboard or plastered on the walls. A poster of Irish birds of prey and the front page of the Irish Times, on the day Nelson Mandela died, are on the same wall as bright yellow Tweety bird stickers and hand-drawn cards. She has received six letters today. One is from a Frenchwoman, wishing her a happy Halloween in French.

The others are from her fiancé Desmond Coutinho, a British-Indian of Goan origin. (They fell in love through an exchange of letters.) She doesn’t open them in front of us. “He said he will visit me on my birthday, which is March 14,’’ she says with a shy, half-hidden smile. No videography is allowed in her room and each visitor is permitted no longer than 20 minutes. Though she is allowed visitors thrice a week, her family members or supporters are rarely permitted to meet the “undertrial prisoner”.

The walls of her room are plastered with posters people have gifted her

The walls of her room are plastered with posters people have gifted her

Solitude fills the days of her life, shapes the hours and flows through the minutes — in the absence of human company, television, phones or internet or even a regular schedule. But she is not lonely, she says. “I have a very busy mind. My thoughts keep me company, they keep me busy,’’ she says. Time means absolutely nothing to her, she says, and you look around and see that there is, indeed, not a single clock on the wall.

Happiness comes from her pets, a pair of guinea pigs she calls Thoi, (“Sometimes I get up in the middle of the night to see if they’re okay. They are my babies.”), the unexpected messages of support from strangers whose lives she has touched with her protest (an Australian woman in Vietnam writes to her regularly, and fasts once every three months in solidarity with her cause). Letters from her family and Coutinho, and the many soft toys that he sends her way give her joy. The newest addition to the menagerie is a brown bear. “He told me that he is like a brown bear, so this is to remind me of him,’’ she says with a laugh.

That laughter and humour, which has survived 14 years of extraordinary bodily deprivation, is as much Sharmila’s resistance against the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act as her refusal to eat or drink, despite the Ryles tube that forces food into her body through her nose. Frail and childlike, she is painfully shy at our first meeting, but gradually warms up, as she speaks about her life before the fast, of the 28-year-old who saw the bloody images of 10 innocent civilians shot dead in Malom by the Assam Rifles in November 2000, and realised she could not eat, until the law that allowed such state violence to flourish with impunity was repealed.

Who was Sharmila before the protest took over her life? Home was a large compound in Porompat colony in Imphal, where an extended family of 19 members lived. She was the youngest of nine siblings, a loner who stood out from the rest of the riotous gang of brothers, sisters and cousins. She was not a sharp child at school, and gave up her dreams of becoming a doctor when she realised she did not have the “brains” for it. She tried but could not clear her Class XII examinations.

Irom Sharmila Chanu

Irom Sharmila Chanu

But she remembers the 2 km walk to school as an adventure. Her father, Irom Nanda, was an attendant in the state veterinary department. To Porompat’s residents, he was Dr Nanda, for the care he would take of their ailing dogs, cows, pigs and other animals. From him, she says, she draws her love for animals and nature. Her father was a great influence in her life. “He was very strict in handling his children but always fair – I think I am like my father that way. He would not even allow us to play games that could become an addiction. Like I was never allowed to play with marbles. But sometimes he would give me a lift to the school on his cycle, and he would tell me many stories on the way,’’ she says.

Hers was a family of modest means, with most occupied in farming or rearing pigs. Though the 1980s were the heights of the insurgency, they lived a sheltered life. Only in their bedtime stories were they told about Manipur’s heroes and those lost in the conflict. “We would hear of the disappearances and about the revolutionaries fighting against the state. It was as if we knew them personally. Sometimes I would imagine them walking up and down our backyard,’’ she says.

But any teenager growing up in Manipur then could not but be affected by the armed forces’ overbearing presence and the daily violence that people faced. “Once I was on my bicycle coming back from a friend’s house. At the corner of a bridge, there were three rickshawpullers, one of them barely a child. His face was half covered with a dirty cloth. An army vehicle drove by. And, suddenly, without rhyme or reason, one of the army guys took his baton and started hitting the boy from inside the vehicle. They just took off after that. I was so shocked. I have never forgotten that,’’ she says.

Though her academic aspirations never quite took off, she did a short course in journalism for six months and learnt stenography for a year. She was still searching for a purpose in life. “But I knew that somehow I wanted to do something for the people around me,’’ she says. She started attending seminars and workshops on women’s rights, the conflict in Manipur and wrote for a local paper called Hueiyen Lanpao.

When the Malom massacre happened on November 2, 2000, she was a volunteer at Human Rights Alert, helping victims of violence, compiling cases and taking part in protests and peace marches.

“I was at a preparatory meeting for a peace rally when I first heard of the incident,’’ she says. It was a Thursday. Like many Hindu Manipuri women, she would fast on Thursdays in the belief that the goddess stepped out of households that day for an “outing’’. The news of the brutal killing of 10 people waiting at a bus stop in Malom left her shaken. She never broke her fast.

“I thought what is the point of working for peace unless we do something drastic. I was so upset that I didn’t eat. At first, I thought, ‘Let me keep lying in bed’. I didn’t even tell my mother that I was still fasting. There was a curfew in Imphal and on the fourth day, I made myself attend a meeting. People sensed something was wrong. They told me I needed to take my fast into the public sphere. So I went to get my mother’s blessing and then I left home,’’ she says.

She remembers the last meal she had had. She had been to a bakery and bought two boxes of sweets. “I don’t remember what they were. But I came back home, sat under the shade of the bamboo grove behind our house and ate them all by myself. I didn’t want to share them with anyone,’’ she says with a giggle.

That fast entered its 15th year this month. Though Sharmila has refused both water and food, the government continues to forcefeed her—and arrests her every year on the charge of attempt to suicide. She is fed Cerelac, juices like Appy, Horlicks and protein shakes—1,600 calories a day.

“She refuses to drink water. So when we have to give her tablets or vitamins, they are crushed with her food,’’ says Dr Th Biren, head of the medicine department at JNIMS, and her attending doctor. A team of six doctors checks on Sharmila daily. “We weigh her periodically. Today she weighs 46 kg, the same as last month. It’s extraordinary what she is doing. Medically, you can be fed through the Ryles tube for months even, as we do with patients with strokes. But for 14 years, that’s unimaginable,’’ Dr Biren says.

Of the day that took away her daughter from her, Sharmila’s 84-year-old mother Irom Sakhi remembers it was the harvesting season. “Everyone was in the paddy fields. Sharmila had stopped talking to everyone, so disturbed she was about Malom. She came and asked me for my blessings. I didn’t know of her intentions, so I blessed her. If I had known, I would never have let her start it,’’ she says.

She knows, however, that she would not have been able to dissuade Sharmila from her mission. “Even as a child, she was stubborn. If she decided to do something, she would do it. So, once I realised what her cause was, I decided to support her. I made her promise that till AFSPA was repealed from Manipur, she would not meet me,” she says. Sharmila is released every year for a day by the court, and promptly rearrested for attempt to suicide. But her mother is the one person she has not met.

A fish pond separates Sakhi’s house from that of her son Irom Singhajit, who runs a trust for Sharmila. Estranged from his family when he married his wife, it was Sharmila who brought him back to the fold. But their relations are now strained. “When Sharmila decided to go on this fast, I decided to leave my job so that I could support her,’’ he says. Singhajit was 41 at the time, working as an agriculture officer in the state government. “When she started fasting, there were all kinds of rumours about Sharmila. Some said she was mad. Others said that she came from a very poor family and was being paid to do this. Another rumour was that she had a boyfriend who died in the Malom massacre. People just could not understand why anyone would do something like this,” he says.

He also remembers Sharmila as different from the rest of the brood, far more connected to nature. “We Meiteis love our fish and meat. But she was vegetarian, sometimes she preferred eating raw vegetables and nothing else,” he says. When she was arrested and taken to jail in 2000, he tried convincing her to give up her fast. “But she said, ‘If you support my fast I will meet you, if you don’t, this is the last time we will ever meet’,” says Singhajit.

Their relations soured when her brother opposed Sharmila’s match with Coutinho — also when allegations surfaced that he had pocketed the money from her awards, refusing to donate it to charities of her choice.

In the 14 years of this remarkable, non-violent protest, much has changed in Manipur. The conflict has claimed more lives, found new icons in victims like Thangjam Manorama Devi, and even corroded Sharmila’s close ties with her brother. Though AFSPA was removed from a few parts of Imphal after Manorama’s rape and murder in 2004, the law has remained what it was. Against the implacable indifference of the Indian state, Sharmila continues to pit her iron will. “People in India see me as a separatist. But that’s not who I am. I am struggling for India’s integrity too. After the way the army has behaved here, if the government does not agree to repeal AFSPA, India will lose Manipur automatically. The government fears that repealing AFSPA will result in losing Jammu and Kashmir to Pakistan as well. I would like to ask the government: why don’t you try and connect to the hearts of the discontented people?” she says.

Bent with old age, Sakhi recalls a child happy with her own company, sitting for hours on the bed, writing and painting. “This is her destiny and she needs to do what she needs to do,’’ she says.

The woman who has willingly taken on the burden of Manipur’s struggle agrees, but she also sees clearly the life that has slipped away from her. One of her strongest memories is of her father taking her to Varuni Hill near Imphal. “I don’t miss my family that much. But I do miss being able to walk up a hill or along a river bank. I miss the wide paddy fields of my land,’’ she says.

Buzzing Now

May 05: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05