- India

- International

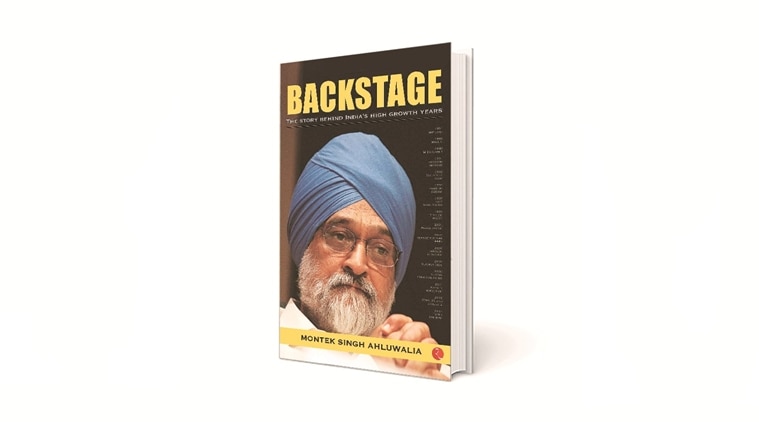

Montek Singh Ahluwalia’s memoir of the reform years presents a complicated picture

It is too easy to dismiss reformers like Montek as elitist. They may make errors of judgment, but they often had more faith in Indians than many of those who yelped loudly in the name of the poor.

Front cover of Backstage by Montek Singh Ahluwalia.

Front cover of Backstage by Montek Singh Ahluwalia.

Name: Backstage: The Story Behind India’s High Growth Years

Author: Montek Singh Ahluwalia

Publication: Rupa India

Pages: 464

Price: Rs 595

When I arrived in Oxford as an undergraduate in 1985, on my very first day my economics tutor asked me if I had heard of a Montek Singh Ahluwalia. I awkwardly said, “No.” In a tone that suggested that I had failed some test, he informed me that Montek was one of the most brilliant students ever to have passed through Oxford. He then added. “He is quite patriotic, you know. Left the World Bank to go back to change your country. If he can’t, no one can.” Montek (as he is now universally addressed) had already set the standard which few could measure up to. In some ways Backstage is a straightforward chronicle of that legendary, brilliant, self-assured and suave economist participating in the momentous changes in India that mirrored his own career. It chronicles the transformation of the Indian economy from a middling performer to a growth dynamo after the reforms.

Montek Singh Ahluwalia. (Express archives)

Montek Singh Ahluwalia. (Express archives)

As a chronicle, it has three singular virtues. The first is the remarkable consistency and clarity of its intellectual outlook. In an age where there is so much condescension of posterity about economic reform, it is worth acknowledging that Montek got the big picture right. Liberalisation and globalisation were a vote of trust, of quiet confidence in the capacity of Indians to rise to any challenge, if only they were let free. It is too easy to dismiss reformers like Montek as elitist. They may make errors of judgment, but they often had more faith in Indians than many of those who yelped loudly in the name of the poor. The book gives a clear, step by step account of the key moments in that reform process and is particularly useful on the build-up to 1991. Second, it is a narrative centred on “reform by stealth”. Reform, for most of India history, was akin to guerrilla warfare. Montek approvingly uses Mao’s advice that guerrillas must move amongst the people like fish in water. But it is important to be clear about what this means. In this case, it does not mean dissimulation or faking positions. It is rather more like knowing when to assert and when to be reticent, when to make a case and when to be satisfied with half-won battles. This appears to be Montek’s singular virtue.

And third, there is the personal humility. The book is telling India’s story; it is remarkably free of the narcissism of so many policy-makers. It also displays a singular commitment to being nice, a determination not to make enemies. Except for mild intellectual irritation at the obtuseness of India’s far left, the book does not have a single negative thing to say about virtually anyone. There is, sotto voce, an implied criticism of the Gandhi family for constraining Manmohan Singh. There is also the rather curious case of VP Singh — who is a surprising figure in this reform story — being removed from the Finance Ministry. Both episodes raise questions of how the Gandhis, at key moment, have frittered away the party’s talents.

But in some ways, Montek’s virtues unintentionally end up showing what went wrong with the establishment of which he was a part. The intellectual clarity and consistency sometimes comes at the price of not taking criticism too seriously. Montek is entirely right about the left’s intellectual framework. He mentions, but gives relatively short shrift to those who argued that the Achilles’ heel of India’s model of development was its abysmal failure in health and education. And perhaps more interestingly, for someone who spent a lot of time thinking about exports and infrastructure, there is relatively little acknowledgement of the fact that the choice of reforms did not do as much for India’s export competitiveness as many had hoped. We were integrating into the global economy without the preconditions that made us competitive. Did India prematurely de-industrialise as a result? Does the intellectual clarity come at the price of being hard-nosed about our reality?

Montek rightly thinks the UPA gets less credit because it did not propagate its achievements. But that was not just because the PM was personally humble. In all fairness, Narendra Modi had to create a narrative about himself to gain legitimacy; the Congress felt so entitled to rule that it thought narratives were irrelevant. But was the problem more interesting? The enticing combination of brilliance, guerrilla tactics, and personal decency and gentility, can work in government only if is combined with a stoic detachment. Both in the book, and as a policy-maker, Montek comes across as the ultimately detached stoic. The only trace of emotion is the use of the word “traumatic” to describe the anti-Sikh riots of 1984, when Arun Shourie had to drive Montek’s parents to safety amidst the carnage. But on almost all other matters, even with hindsight, there is a supreme reluctance to call out dangerous nonsense. The issue is not personal gossip; it is holding principals to account.

Montek is clear that UPA2 went off the rails. He hints that Pranab Mukherjee was one of the culprits. But you do want to know what Montek was thinking, when Pranab Mukherjee was taking a wrecking ball to the economy with the PM and him watching. One simple sentence is actually quite a takedown of the RBI. Montek argues that an independent regulator for banks would have done a better job. It is now clear that one of our most dismal regulatory failures has been the RBI’s supervision of banks, across governments.

But can something as disastrous as the regulation of Indian banking be contemplated with a lapidary detachment? Does guerrilla warfare then become another synonym for not offending anyone to the point that the line between being a reformer and being the establishment becomes meaningless? The ultimate price of stoicism was that guerrilla warriors of reform became hard to distinguish from the corruption and lethargy of the establishment. But whatever the end of UPA2, no one can take away from the fact that this brilliant reformer did help change India for the better, in ways that few can rival.

Mehta is contributing editor, The Indian Express

Buzzing Now

May 04: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05