- India

- International

As India gets a new Parliament, a look at the history of the first legislative office, from a room to an institution

Chakshu Roy on the 97-year-old building whose corridors and columns stand witness to a vast arc of history – from the time that it was the Council House of British India to when it became Independent India's first Parliament House, from the chaos of argumentative debates that shaped the world's biggest democracy to the consensus marked by loud thumping of desks that shaped many a legislation.

The much larger circular building in Delhi was inaugurated in 1927 by Governor-General Lord Irwin. Illustration Credit: Intach, Delhi Chapter

The much larger circular building in Delhi was inaugurated in 1927 by Governor-General Lord Irwin. Illustration Credit: Intach, Delhi Chapter Roughly a century ago, when the foundation stone of the original Parliament House was laid, the building was an afterthought. In the new capital city of Delhi, the focus of finance and attention was the Governor-General’s (President’s) House.

The Council House was built to accommodate a newly created legislature. Legislative institutions have a long history in India. Under the charter given by the British government in 1601, the officers of the East India Company had the power to make laws. A council of the company’s senior officers carried out the corporation’s administration in Bombay, Madras and Calcutta. These settlements were independent, each with its committee, and their meeting venue was a room called the Council Chamber in the respective cities.

The company’s fortunes would wane, and in 1833, the British, through law, would strip the company of its trading rights. This law would also separate the executive and law-making functions of the Council and set up one Legislative Council for all British territories in India. Another legal change in 1861 would form a “central though rudimentary” legislative body.

The venue for this legislative body’s meetings was the Council Chamber on the first floor of the Government House in Calcutta. The Indian Penal Code of 1860, which defines crime and punishment in the country, was discussed and passed in this Council Chamber. The British constructed another Council Chamber in the viceregal residence in Shimla for the legislative council meetings when the government moved to the hill city in the summers. In 1911, King George V announced that the capital of British India would move to Delhi and laid the foundation stone for a new capital city. The move led to adding a Legislative Council chamber in the government secretariat building in old Delhi.

It also raised a question of whether there would be a separate building for the meetings of the Legislative Council in the new capital city. Till then, the Legislative Council was a unicameral body, and the strength of its membership had risen to 60 in 1909. Its meetings were held in the large council chambers in Calcutta, Shimla and Delhi.

Ideas for New Delhi’s Legislative Council Chamber

During the planning phase of the construction of the new capital city of Delhi, the British had no intention of having a separate building for the Legislative Council. In 1912, a House of Commons MP questioned this move. In his reply, the under-secretary for India, Edwin Montagu, stated that the Legislative Council would meet in a hall in a separate wing of the Governor-General’s official residence. However, Montagu favoured a separate building. Jane Ridley, the great granddaughter of British architect Edwin Lutyens, writes in his biography that both Lutyens and Montagu had urged Lord Hardinge, the first Governor-General of India, for a separate building for the Legislative Council. Hardinge had refused, stating, “No – I, as Governor General with my council, govern India, so it must be in my house!”

As a result, in 1913, when Lutyens and Herbert Baker signed on to be the architects for the new capital city of Delhi, their brief only included the design of the ‘Government House (the present President’s House)’ and ‘Two principal blocks of Government of India Secretariats and attached buildings (North and South Block)’. As part of the Government House, they were to design a Legislative Council Chamber, a library and writing room, a public gallery and committee rooms.

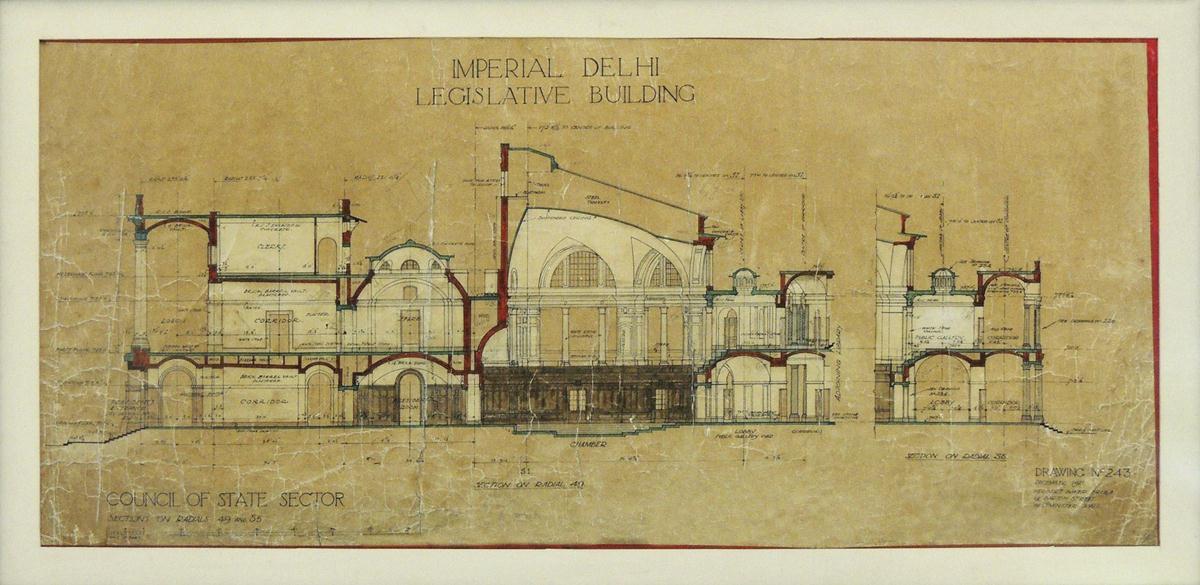

A drawing of the proposed imperial legislative building in Delhi.

A drawing of the proposed imperial legislative building in Delhi.

Six years later, constitutional reforms recommended by Montagu (and Lord Chelmsford, the Governor-General who succeeded Hardinge) led to the passing of the Government of India Act 1919. This law envisaged a bicameral legislature with a 60-member council of state and an elected legislative assembly with a strength of 140 members. It presented the planners of Delhi with the problem of finding a suitable building where the bicameral legislature could hold its deliberations.

The administration in Delhi made two proposals for temporary accommodation for the newly created institution. The first was outlandish, which was to house the legislative assembly in a shamiana (tent). The officers deciding the matter, however, rejected the proposal.

The other suggestion was to refurbish an existing building to house the legislature. The administration accepted this proposal and constructed a larger assembly chamber in the secretariat building in Delhi, and the Legislative Council held its meetings in the nearby Metcalf House. These were temporary arrangements, and Baker was tasked with designing the new Council House. The new building had to accommodate three legislative chambers, the assembly, the council and a council of princes (Narendra Mandal), which a royal proclamation established after the 1919 Act.

The Original Plan

The committee responsible for the construction of the capital city of Delhi decided that the new building would be located at the base of Raisina Hill, below North Block. The plot of land for the new Council House was a triangle in shape. The need to accommodate three chambers and the form of the plot led Baker to design a triangular building. His design showed the three legislative chambers as the three wings of the building connected by a central dome.

By this time, the ongoing dispute over the road gradient leading to Government House had deteriorated the relationship between Lutyens and Baker. And, in 1920, when Baker presented his triangular design for the Legislative Council building to the committee, Lutyens bitterly opposed it and wanted a circular structure.

In a letter to his wife, he described the proceedings as: “I gave Baker no trust and the design he put forward did not fit the site… One façade was a dreadful untidy arrangement and his excuse was that he had not worked on it but that it would be all right. I went for him and told the committee that Michelangelo could not make anything of it nor could God himself unless he worked by miracle and against the laws that govern the world.”

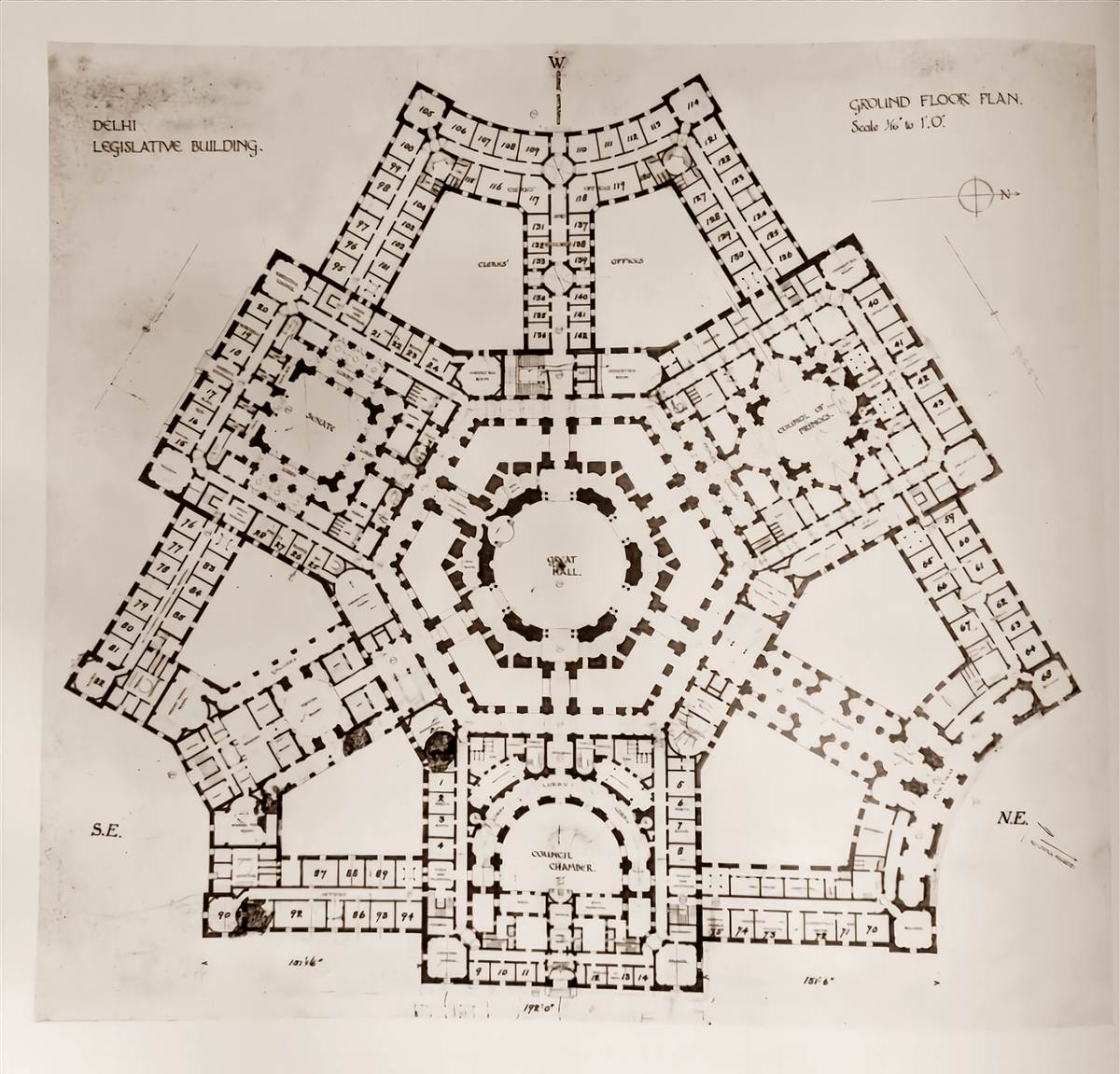

Baker’s original floor plan of Parliament House. Had it gone through, India would have had a differently shaped Parliament building.

Baker’s original floor plan of Parliament House. Had it gone through, India would have had a differently shaped Parliament building.

Baker submitted a lengthy memorandum to the committee, defending the triangular design. He also suggested an alternative site away from Raisina Hill for the Legislative Council building. He wrote, “The criticism of the previous triangular plan was that its form had been dictated less by the nature of the buildings than by the geometrical limitations of the site. The criticism applies with equal, if not greater, force to the present circular plan… and it is a matter for consideration whether this circular form of building, however beautiful it may be made in itself, will give distinct impression to the sentiment of the national Parliament which India will look for in this building.”

In the end, Lutyens convinced the committee for a complete redesign from a triangular to a circular building. A jubilant Lutyens wrote, “I have got the building where I want it & the shape I want it.” A dejected Baker using a cricketing metaphor told Lutyens that the committee had given him “out” and recast his winged triangular design to fit a circle. The final design had three semi-circular chambers and a big central hall for the library.

The Duke of Connaught, Prince Arthur, laid the foundation stone of the Council House building in 1921, and excavation of its foundation started a year later. The completed building has a diameter of 570 feet. It has a base of red sandstone, which is 22 feet high. On this base stands a colonnade of 144 columns, each 27 feet tall.

The construction required 3,75,000 cubic feet of stone quarried from Dholpur in Rajasthan and brought to Delhi by train. A circular track around the building brought the stone closer to the site. Inside the building, the marble used came from Gaya (Bihar) and Makrana (Rajasthan). The timber is from Assam, Burma and the southern part of the country.

Baker also gave special attention to the acoustics in the legislative chambers. A collaboration between architects, academics, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist and an engineer of Spanish origin brought acoustic clarity to the building. Forty thousand acoustic tiles were imported from the US and attached to the roof of the legislative chambers.

While the Council House was coming up in Delhi, a smaller building was also being constructed in the summer capital, Shimla. It was meant for the Legislative Assembly sessions held in the city in the summer months. The building was inaugurated in 1925 and is now the home of the Himachal Pradesh Legislative Assembly.

The New Circular Building

The much larger circular building in Delhi was inaugurated in 1927 by Governor-General Lord Irwin, who read a message from King George V. It stated, “The new capital which has arisen enshrines new institutions and a new life. May it endure to be worthy of a great nation and may in this Council House wisdom and justice find their dwelling place.” Baker presented Irwin with a golden key to open the building door at the inauguration. And the day after the inauguration, the Legislative Assembly started functioning from this building.

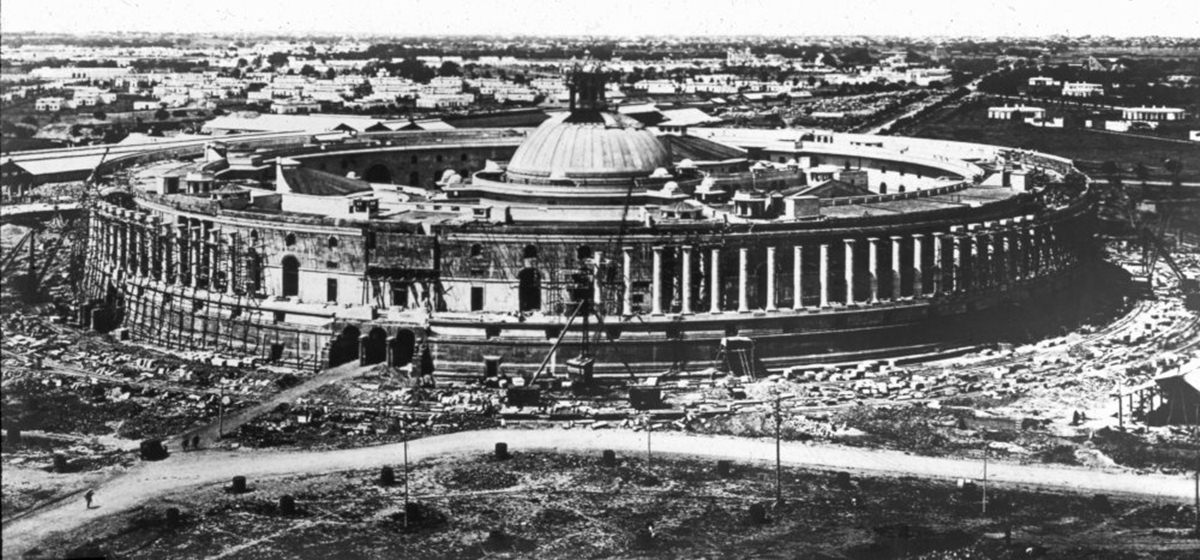

Construction underway at the site of the old Parliament building. Credit: Royal Institute of of British Architects/Archives

Construction underway at the site of the old Parliament building. Credit: Royal Institute of of British Architects/Archives

The newly constructed Council House would run out of space in less than two years. An attic storey made from plaster (to save money) would be added to the circular building for offices for the growing assembly staff. The animosity that Lutyens had for Baker would raise its head again after the inauguration of New Delhi. Lutyens’ biography mentions that he would take revenge on Baker by manipulating publicity back home.

A young travel writer Robert Byron was hired by two influential British magazines to review the Delhi buildings. Byron, who was neither an architect nor an architectural historian, would severely criticise Baker’s design of the Council House. He described the building as “a Spanish bull-ring, lying like a mill-wheel dropped accidentally on its side”.

New Names for the Old

When India started on the path of Independence, the Council House became a hub of activity. The library in the centre of the building was renamed Constitution Hall. Benches were added to it to accommodate the 300-plus members of the Constituent Assembly, who would draft the country’s Constitution in this domed hall. In the legislative assembly chamber, the members of the Constituent Assembly legislative met to enact laws for a newly independent India.

Entrance of the Central Hall of Parliament House. Express archive photo by RK Sharma, September 1991

Entrance of the Central Hall of Parliament House. Express archive photo by RK Sharma, September 1991

The birth of a new nation requires space for its institutions. The chamber of princes was converted into a courtroom, and the Federal Court, and afterwards, the Supreme Court, would sit there till 1958. The Federal Public Service Commission, the predecessor to the Union Public Service Commission, also functioned from the circular building for a few years before moving out in 1952.

Independence also meant a change in terminology, and the Council House became Parliament House. There were other changes. After the Constituent Assembly completed its work, the Constitution Hall became Central Hall, a venue for MPs to interact and hammer out differences over tea and coffee. And, in 1954, the presiding officers of the two Houses changed the name of the House of People to Lok Sabha and the Council of State to Rajya Sabha.

Portraits on the Wall

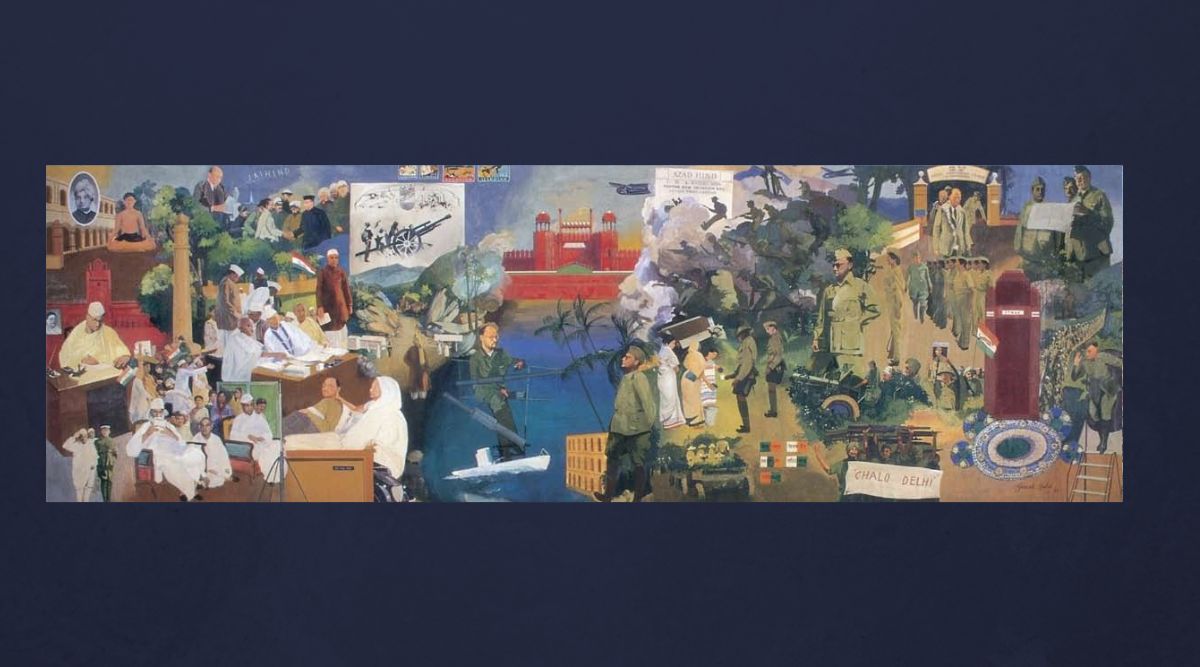

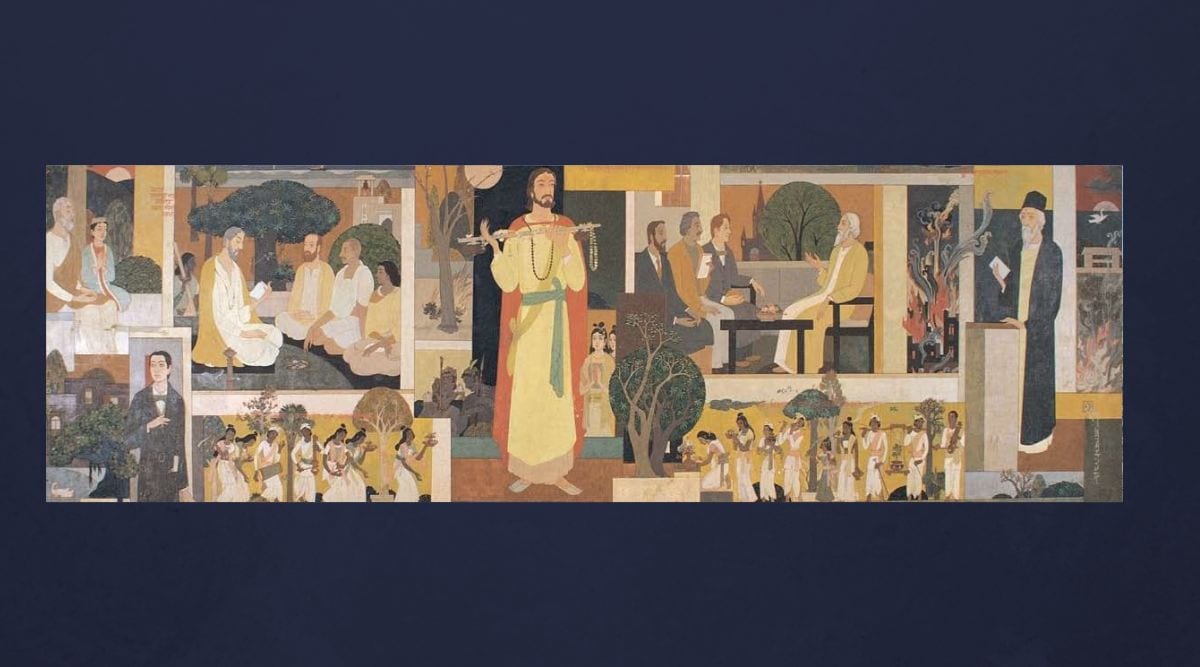

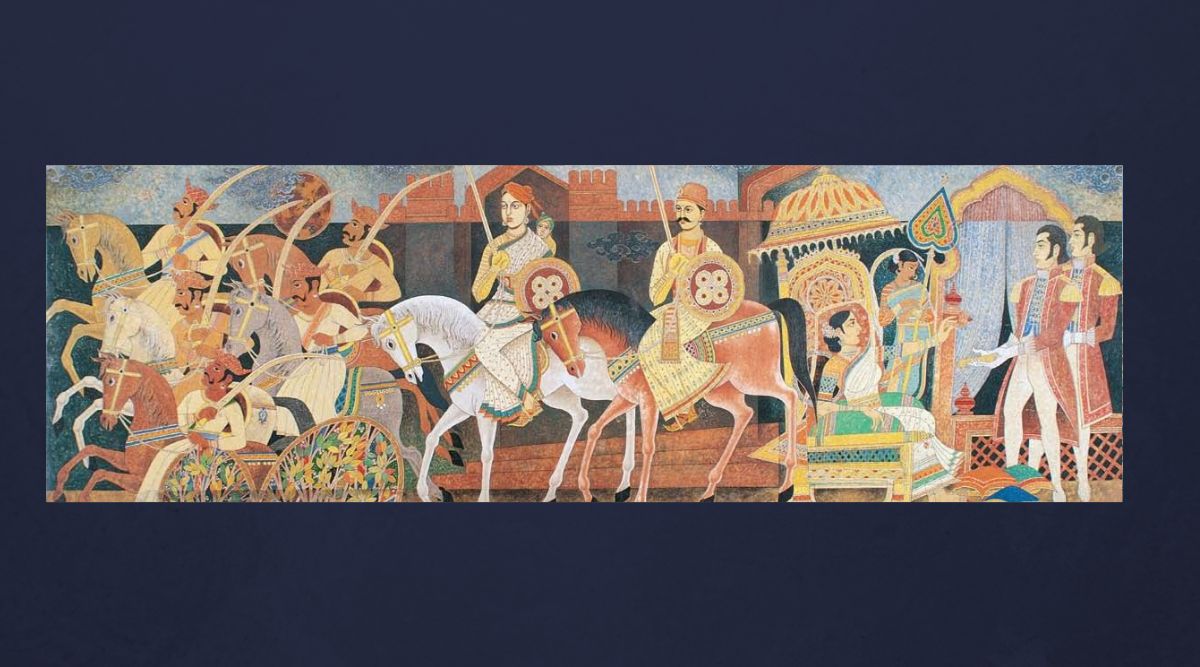

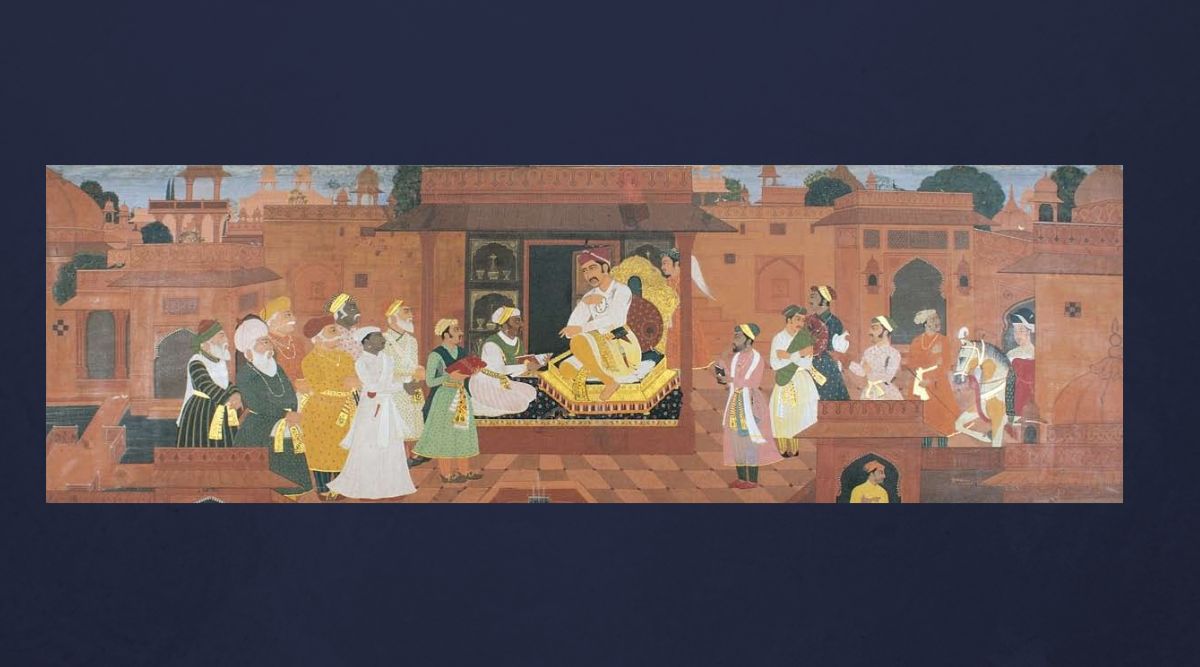

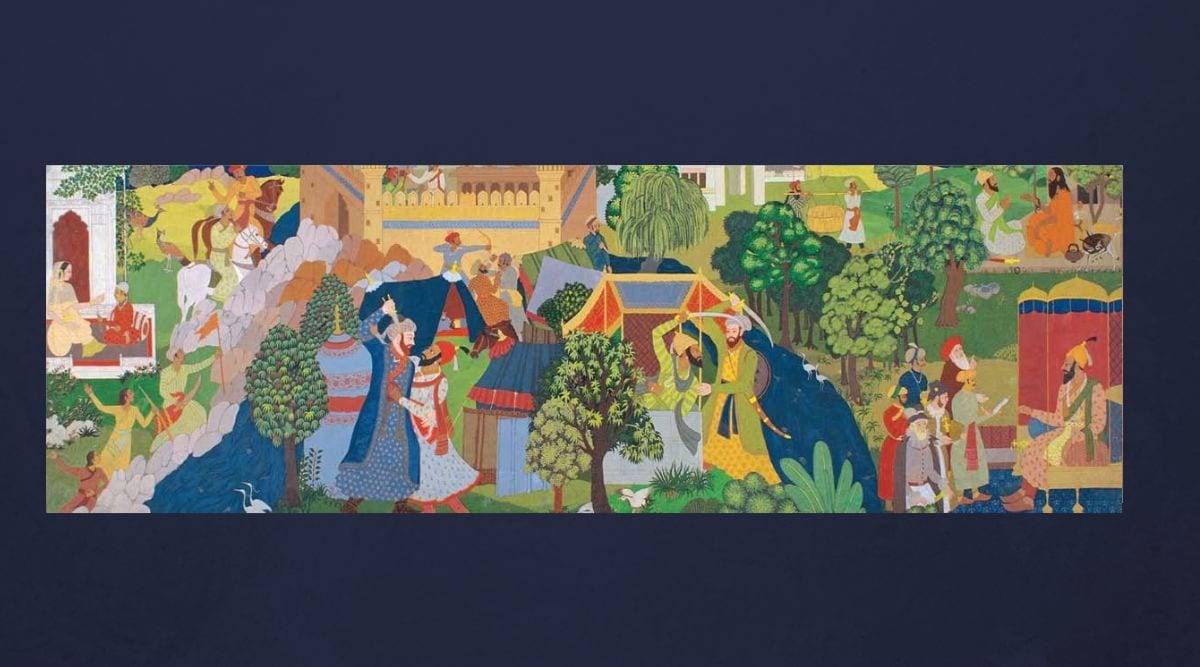

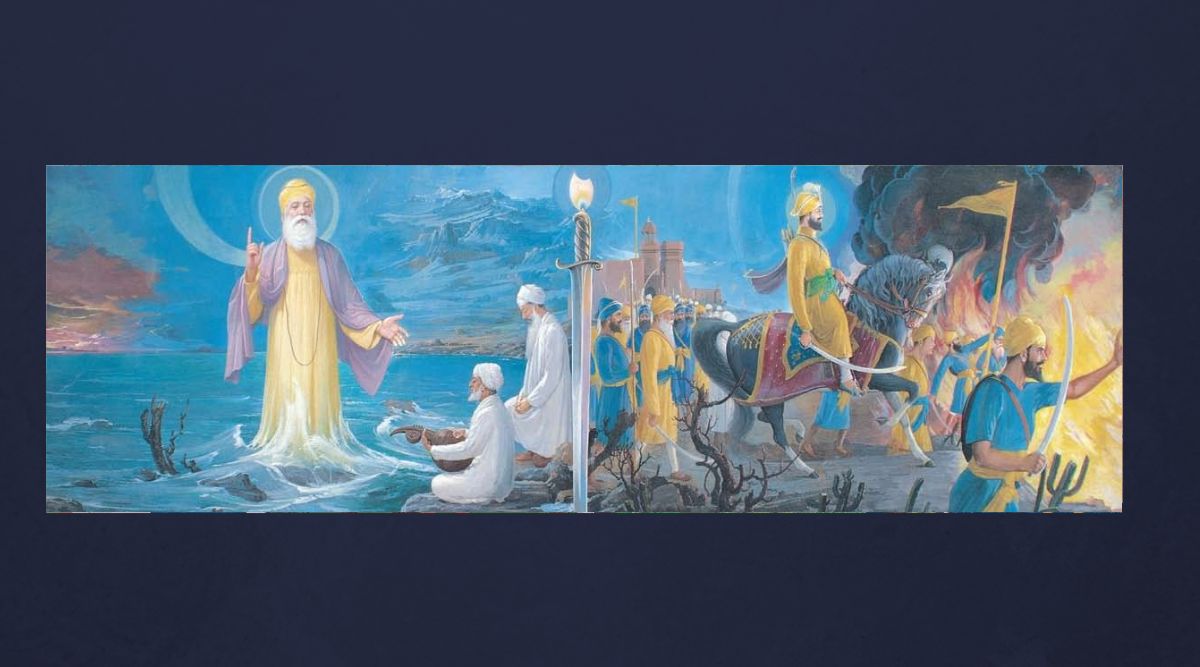

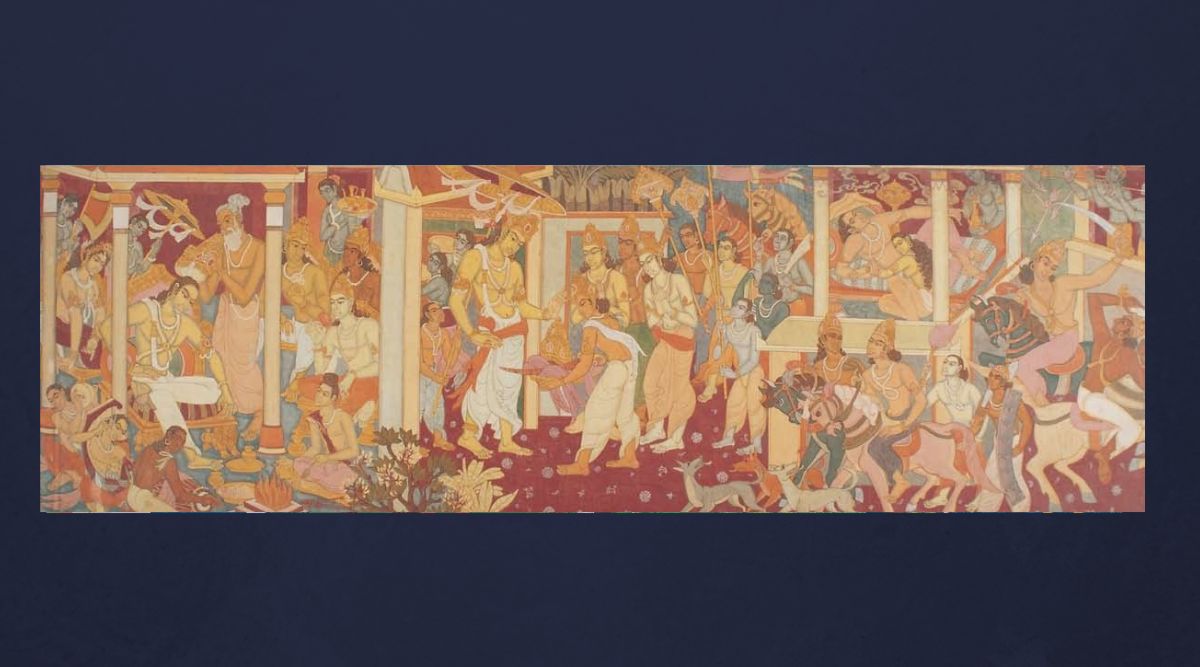

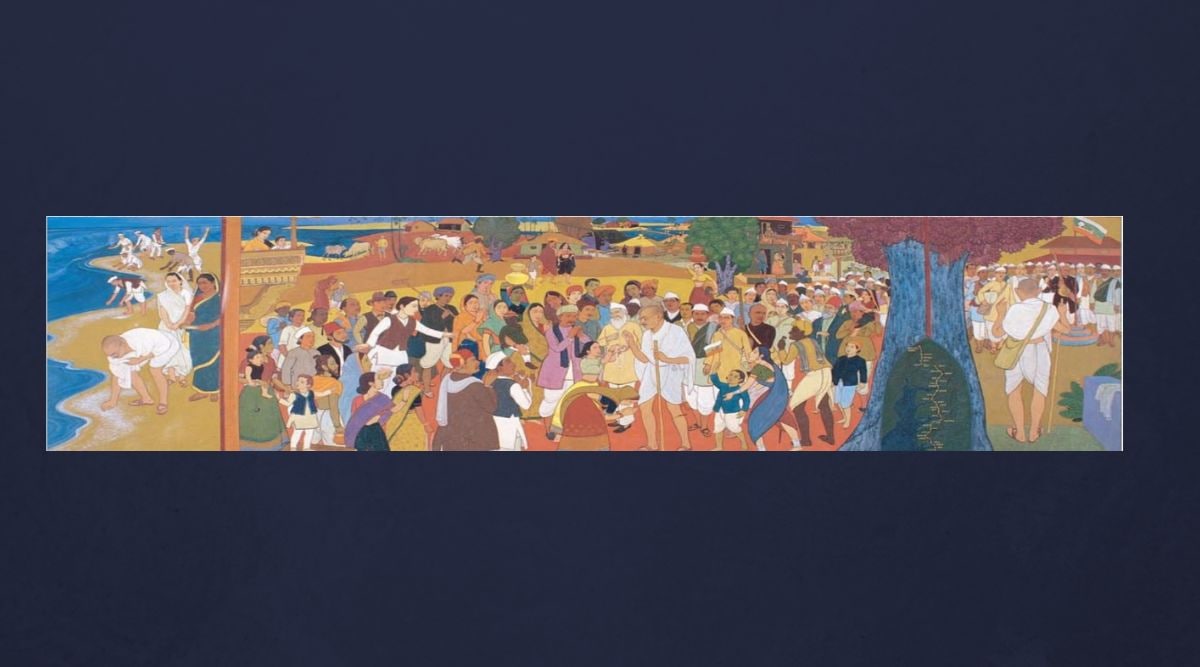

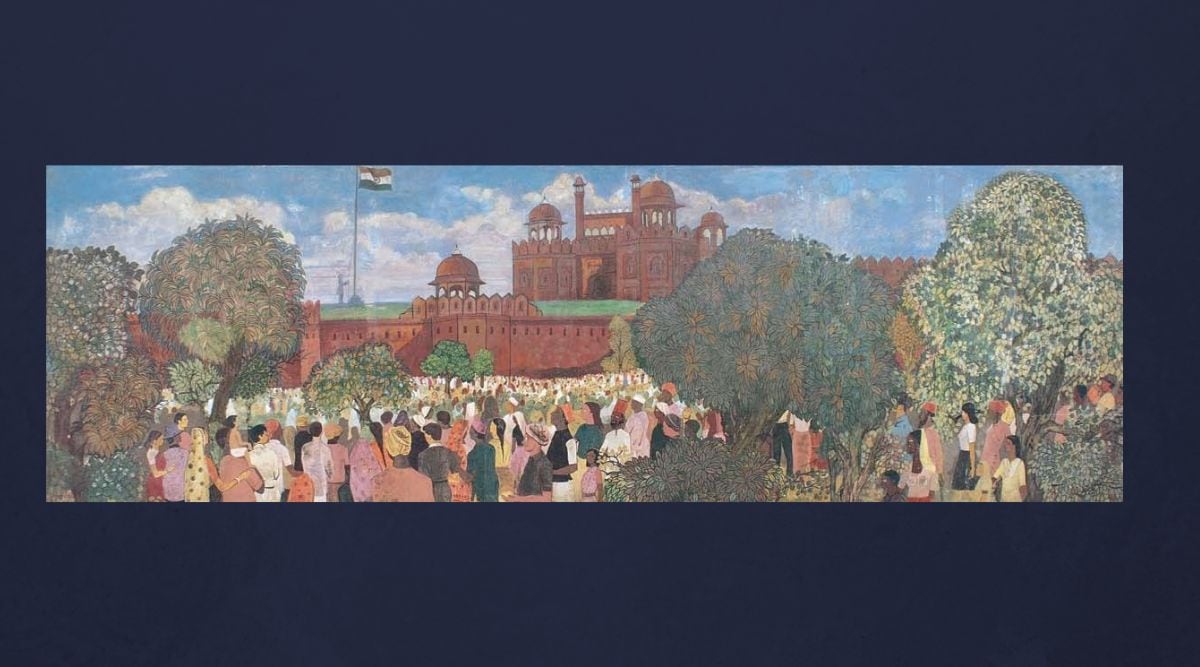

When the Council House was built, its walls were bare as there was hardly any budget for its decoration. The first Speaker of Lok Sabha, Shri GV Mavalankar, appointed a committee to recommend a scheme for the decoration of the building. The committee recommended that the ground floor walls of the building be painted with murals depicting events from the country’s rich cultural heritage.

As part of its discussions, the committee also considered placing the statues of national leaders in the 50 or more niches on the ground and first floors of the Parliament. Following the committee’s report in 1953, work started on the murals. Artists from across the country painted 58 murals showcasing the idea of India from its inception to independence.

Parliament House is also full of portraits and statues of personalities who have shaped the country’s history. In the Lok Sabha chamber, facing the Speaker’s Chair, is the portrait of Vithalbhai Patel, the first Indian presiding officer of the Central Legislative Assembly. Similarly, the Rajya Sabha chamber has one of Dr Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, the first chairman of the House. The lobbies of both Houses display the pictures/portraits of the presiding officer of the respective House.

The Central Hall of Parliament also doubles up as a portrait gallery. The first portrait to adorn it was that of Mahatma Gandhi in 1947, and the last in 2019 was that of Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee. All the paintings are gifts from individuals or associations who collected money for this purpose. For example, MPs contributed money for the portrait of Prime Minister Jawahar Lal Nehru, painted by the Russian artist Svetoslav Roerich.

There are 50 statutes in the Parliament complex, possibly the maximum outside of a museum in the country. Before 1993, only five statues (Motilal Nehru, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, B R Ambedkar, Lala Lajpat Rai and Sri Aurobindo) were in its precincts. In 1993, during the term of the minority government of Prime Minister Narasimha Rao, Lok Sabha Speaker Shivraj Patil revived the earlier plan of placing statues in Parliament.

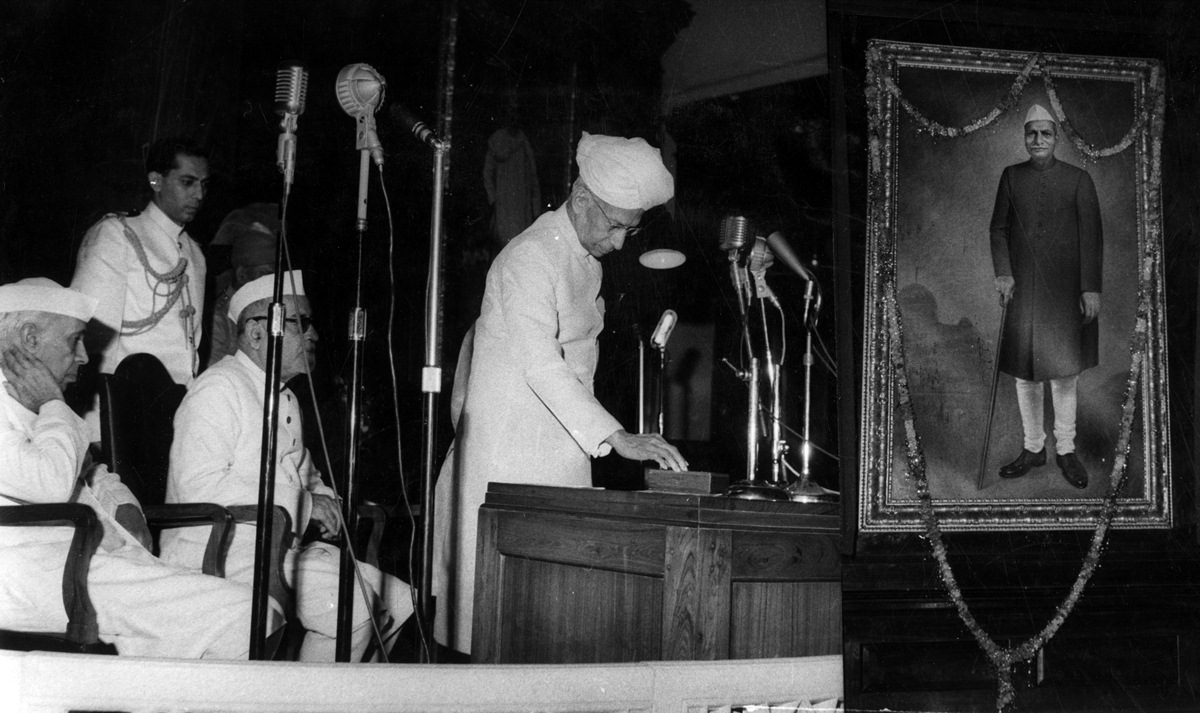

President S Radhakrishnan pressing the button to unveil a portrait of the late Dr. Rajendra Prasad in the Central Hall of Parliament House in New Delhi on May 5, 1964. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Vice President Dr. Zakir Hussain are also seen. Express Archive Photo

President S Radhakrishnan pressing the button to unveil a portrait of the late Dr. Rajendra Prasad in the Central Hall of Parliament House in New Delhi on May 5, 1964. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Vice President Dr. Zakir Hussain are also seen. Express Archive Photo

He announced that a committee of senior parliamentarians had recommended the installation of figures of “the great sons and daughters of India.” The first one to be unveiled in 1993 was that of Mahatma Gandhi. This 16 feet statue of the Mahatma in a meditative pose is the preferred venue of protests by MPs during a parliamentary session. Since then, the statues of leaders from across the political spectrum have been installed in Parliament.

Update, Upgrade

In addition to the artwork and statutes, after Independence, the Parliament building also got a technological upgrade. A new sound system and brighter lighting were the first things to be installed. And, in 1957, the two Houses were equipped with an automatic vote counting machine. Because of the proximity in the seating of MPs in Parliament, the system was designed in such a way that MPs had to use both their hands while voting, the idea being that MPs should not be able to press the voting buttons of their colleagues who might not be present.

Before the new voting machine could be put to use, a problem was highlighted to the Speaker. One of the MPs was differently abled and had only one hand, and the machine required the use of both hands. The solution provided by the Speaker was that an officer of the House would help the MP vote. In this instance, much to the Speaker’s displeasure, rather than wait for the officer’s assistance, fellow legislators helped the MP cast his vote.

The iconic circular building gets the most attention. But it is not the only building in the Parliament complex. After Independence, there was an increase in legislative activity, and the Parliament needed more office space and committee rooms. In response, the Parliament Secretariat started the construction of a new building called the Sansadiya Soudha (Parliament Annexe).

The new building was positioned north of the Parliament House across Talkatora Road. President VV Giri laid the foundation of this building in August 1970. Speaking on the occasion, the Minister for Housing and Urban Development, KK Shah, recalled that Speaker Ganesh Vasudev Mavalankar had first mooted the idea of a new office building in 1952.

Shri Shah said, “His [Shri Mavalankar] was an imaginative plan for three separate buildings on three plots adjoining the Parliament House — one for the Parliamentary Parties/Groups and individual Members, second for the Parliamentary Library and Auditorium, and a third for housing the Committee rooms and their offices and the Secretariat for the two Houses — all of them forming part of the Parliament Estate.”

In his vote of thanks, Speaker GS Dhillon revealed that during the design stage of the Annexe building, there was a plan to build a subway underneath Talkatora Road and connect it to Parliament House. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi approved the proposal. The planners also investigated the feasibility of having a monorail or a mobile walk within the subway. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi inaugurated the Annexe building in 1975.

The subway plan never materialised, and MPs had to cross the busy road to access either building. After the 2001 Parliament attack, the section of Talkatora Road that separated the two buildings was included in the grounds of Parliament.

In 1987, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi laid the foundation stone of the next building in the Parliament complex called the Sansadiya Gyanpeeth (Parliament Library). President KR Narayanan inaugurated it in 2002. The Parliament Library, located in the circular building, shifted to a modern purpose-built space in this new building. The original calligraphed copies of the Constitution, kept in airtight nitrogen-filled cases in the circular building, were also moved to a special room inside the library building. When office space in the Annexe ran out, an extension was built, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated it in 2017.

Signs of Age

The Parliament building is now in its 97th year and has started showing visible signs of age and neglect. For many years, there were unplanned changes to the structure. Empty spaces were converted into offices, claimed for storage or became dumping grounds for unrequired material. The condition was much worse on the upper floor of the building, away from the public eye. Former Secretary General of Rajya Sabha, Vivek Agnihotri, said he was “dumb-struck by the conditions in which several lower-level officers and staff members were accommodated on the second floor of the main building.” He stated, “The total ambience looked somewhat vandalised on account of various ad hoc additions and so-called improvements made to the structure within.”

Lack of proper maintenance has also contributed to the distress in the building. In its 1986 report, a Parliamentary committee was scathing in its criticism of the Central Public Works Department, which is responsible for the maintenance and upkeep of the heritage structure. The committee observed, “In a period of less than 60 years, which is a short span in the life of a historical and prestigious building of the stature of Parliament House, the edifice has developed ugly scars when viewed minutely. Though the imposing massive structure still looks very sturdy from outside, it has been shaken to its very foundation by the inexplicable and inexcusable neglect, apathy and carelessness shown by the CPWD in its proper and much needed maintenance.” The committee then went out to detail serious issues related to the building.

Repair and refurbishing work underway at Parliament House in New Delhi ahead of a new Lok Sabha term. Express Photo by Tashi Tobgyal, May 2019.

Repair and refurbishing work underway at Parliament House in New Delhi ahead of a new Lok Sabha term. Express Photo by Tashi Tobgyal, May 2019.

But what was known only to insiders started coming out in the open after a series of mishaps. In June of 2009, a part of the ceiling of the ground floor office of Petroleum Minister Murli Deora collapsed. Storing LPG cylinders for the canteen on the floor above the office caused the incident. This newspaper reported that the Deputy Chairman of Rajya Sabha observed, “It is a matter of grave concern and carelessness that in the Parliament House, a heritage building, this kind of incident was allowed to happen.” He went on to state, “Similarly, the damage of the structure due to water seepage is also a serious issue, and if immediate action to shift the canteen and wash area is not taken, it may have serious implications, including the safety of the occupants in the offices on the ground floor.”

Over the years, there have also been minor incidents of fire and multiple incidents of foul smell due to blocked sewer lines and air conditioning ducts. More recently, in 2012, the proceedings of the Rajya Sabha were interrupted for half an hour due to a stench in the House. These incidents led to Meira Kumar, the then Lok Sabha speaker, stating that the parliament building was “weeping”. The next Speaker, Sumitra Mahajan, echoed similar views when she wrote to the Urban Development Ministry that the iconic circular building showed “signs of distress”.

The roughly 100-year-old Parliament House is now ready to pass the baton to its newer counterpart next door. This time, things are a little different. The new Parliament is the cynosure of all eyes and the focus of the Central Vista redevelopment. Hopefully, it will continue to be a forum for passionate debate for the next hundred years.

May 12: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05