- India

- International

The colonial — and anti-colonial — roots of Durga Puja

This brief history of Bengal’s greatest festival will discuss the Battle of Plassey, the rise of native Bengali elites under Company rule, and of course, the national movement.

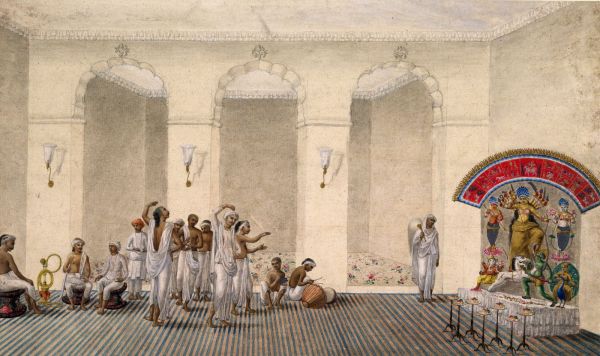

A Durga Pujo celebration in Calcutta during the 1830s-40s. Take note of the palatial house (belonging to an Indian zamindar/merchant) and the Europeans (front row, seated) being entertained by nautch girls. It is this tradition that made Durga Pujo as much a festival of merrymaking as of worship. (Painted by William Prinsep with watercolour, Wikimedia Commons)

A Durga Pujo celebration in Calcutta during the 1830s-40s. Take note of the palatial house (belonging to an Indian zamindar/merchant) and the Europeans (front row, seated) being entertained by nautch girls. It is this tradition that made Durga Pujo as much a festival of merrymaking as of worship. (Painted by William Prinsep with watercolour, Wikimedia Commons) As the oppressive heat of the Indian summer gives way to the gentle chill of autumn, an air of excitement covers Bengal, and eastern India. It is time for Goddess Durga’s homecoming, celebrated by Bengalis as Durga Puja — as much a religious occasion as one for frivolous merrymaking.

As this year’s festivities enter into full swing, we look at the history of modern Durga Puja, and how it emerged under colonial rule.

Robert Clive and a myth that is a metaphor

Durga Puja has many apocryphal origin stories. The most popular is set in the aftermath of the Battle of Plassey, in 1757. By defeating Nawab Siraj ud Daula, Robert Clive changed the course of Indian history, cementing East India Company’s hold over Bengal, and eventually, the whole subcontinent. The victory also made Clive a very rich man.

The deeply religious Clive credited God for unbelievable fortune, and wanted to hold a grand ceremony in Calcutta to convey his thanks. The former Nawab, however, had razed the only church in the nascent city. So in stepped Nabakishan Deb, Clive’s Persian translator and close confidante. Deb told Clive to come to his mansion instead, and make offerings to Goddess Durga — thus began Calcutta’s first Durga Puja.

Robert Clive (standing, hand extended) meets Mir Jafar, the defector who effectively guranteed British victory against the Nawab. (Painted by Francis Hayman, Wikimedia Commons)

Robert Clive (standing, hand extended) meets Mir Jafar, the defector who effectively guranteed British victory against the Nawab. (Painted by Francis Hayman, Wikimedia Commons)

Deb’s mansion in Sovabazar, preserved today by West Bengal tourism, still hosts what is colloquially known as “Company Puja”. Yet, this story does not pass muster. There is no record of Deb knowing Clive, let alone being a close confidante, prior to 1757. There is also no evidence of the Puja actually taking place that year, except for an anonymous painting. While the Sovabazar Puja is undoubtedly among the oldest in Calcutta, its origin story is highly suspect.

Nonetheless, the story serves as a metaphor for the sociological origins of Durga Puja in Calcutta. Put simply, the origins of modern Durga Puja can be credited to the nexus between Bengali zamindars and merchants, and the East India Company.

A status symbol in a churning society

With Company rule in Bengal came a host of social and economic changes. Most notable, in the story of Durga Puja, was the rise of a new class of powerful natives who reaped the benefits of Company rule.

First were zamindars, or hereditary landowners. After the decline of the centralised Mughal state, zamindars in Bengal had become increasingly assertive, effectively running their own fiefdoms. The Company effectively treated them as intermediaries between themself and the native population, with the Permanent Settlement Act of 1793 solidifying their position.

Then there was the emergent class of rich Bengali merchants, especially in the fast-growing urban centre of Calcutta. With Company rule came economic opportunity at a scale not seen before — some people got very rich, very quickly. Thus emerged big mercantile families such as the Tagores or the Mullicks.

“For the nouveau riche, the products of the East India Company’s trade and their tenurial system, Durga Puja became a grand occasion for the display of wealth and for hobnobbing with the sahibs,” historian Tapan Raychaudhuri wrote in an essay titled ‘Mother of universe, Motherland’.

Early 19th century Durga Pujo. From the beginning, Durga Pujo was an occaision for fun and revelry. (Patna Style, unknown painter, Wikimedia Commons)

Early 19th century Durga Pujo. From the beginning, Durga Pujo was an occaision for fun and revelry. (Patna Style, unknown painter, Wikimedia Commons)

According to Raychaudhuri, “conspicuous consumption rather than display of bhakti” was the central motif of these festivals. Rival families would compete against each other to host the grandest Puja possible — idols would be adorned with gold, nautch girls would be hired from as far away as Lucknow and Delhi, even the British governor-general would be called as the chief guest. “During Puja … People spent as much time on looking at the images [of the Goddess] as on window-shopping at the establishments in the red-light district,” Raychowdhuri wrote.

In this way, Puja became an occasion to merry-make as much as worship the Goddess.

Puja takes a nationalist turn

By the late 19th century, feelings of nationalism emerged in the Bengali population, especially the educated intelligentsia. Bankim’s Ananda Math was published in 1882. A fictionalised version of the late 18th century Sanyasi Rebellion, the novel popularised the phrase “Bande Mataram” — putting into popular consciousness the imagination of the “nation” as the “mother”.

Goddess Durga, worshipped as “Ma” (or mother) Durga, thus became the ultimate embodiment of the nation, as well as the figure who would act as its saviour from foreign rule. Durga Pujas were suddenly a part of the nascent nationalist project.

This meaning became particularly pronounced after Lord Curzon’s decision to Partition Bengal in 1905. ‘Bande Mataram’ became the battle cry of the ensuing Swadeshi Movement, considered to be the first mass movement of the Indian freedom struggle, communal festivities became places where collective consciousness and action was forged.

Historian Rachel McDermott wrote about Durga Pujas of the time in Revelry, Rivalry and Longing for the Goddess of Bengal (2011). “Bengali newspapers were full of advertisements for the Poojahs, nothing bideshi [foreign], everything swadeshi [indegenous]: indigenous oils, silks, dhutis, saris, shoes, tea, sugar, and cigarettes with brands named like Vidyasagar, Sri Durga, and Durbar,” she wrote.

At the Pujas themselves, British elites were far less welcome than before. “One British officer reported that he had seen an image of Durga where the buffalo demon had been replaced by one of his colleagues,” Raychaudhuri wrote.

In the 1920s, public Pujas began to emerge — from being a festival of wealthy Bengali elites, Puja started to become a festival for everyone. According to McDermott, this was both an outcome of Gandhian rhetoric against untouchability as well the need for Hindu consolidation.

The first sarbojanin, or “universal,” Puja was organised in 1926, in Maniktala in Calcutta. McDermott explained that these were organised “by locality rather than by clique”, and were “open to all”, regardless of birth (caste) or residence. “For the first time, pandals, or temporary temples made out of bamboo or cloth, were constructed in public thoroughfares, alleyways, and cul-de-sacs,” McDermott wrote.

More Explained

EXPRESS OPINION

May 12: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05