- India

- International

Did Hindu kings destroy Buddhist structures in ancient India? This is what history suggests

Samajwadi Party leader Swami Prasad Maurya, last week, called for an archaeological survey of Hindu temples, to determine whether they have been built over Buddhist structures. This happened in context of the ongoing Gyanvapi mosque issue.

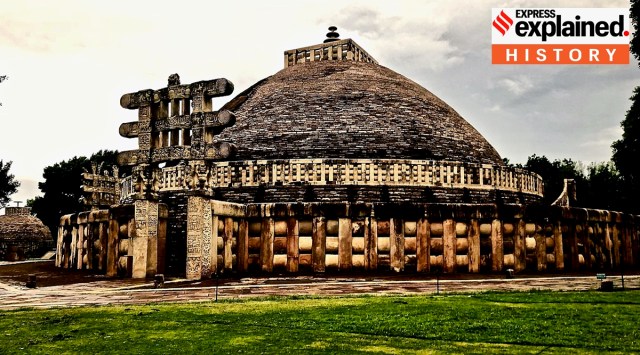

The Sanchi Stupa near Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh. At the peak of Buddhism in the subcontinent, Buddhist stupas and monasteries were a common site. Today, most are either in ruins or missing altogether. (Wikimedia Commons)

The Sanchi Stupa near Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh. At the peak of Buddhism in the subcontinent, Buddhist stupas and monasteries were a common site. Today, most are either in ruins or missing altogether. (Wikimedia Commons) Samajwadi Party leader Swami Prasad Maurya has called for an archaeological survey of Hindu temples to determine if they were built after destroying previously existing Buddhist structures.

Maurya spoke last week amid the ongoing litigation around the Gyanvapi mosque complex in Varanasi. “If you want to do a survey on what structures existed before [present day] mosques, you should also survey [to find out] what existed before those structures. Many temples were constructed after destroying Buddhist religious sites,” Maurya said.

He mentioned Badrinath as an example, and claimed the temple in Uttarakhand was built in the 8th century on the site of a Buddhist monastery.

आखिर मिर्ची लगी न, अब आस्था याद आ रही है। क्या औरों की आस्था, आस्था नहीं है? इसलिए तो हमने कहा था किसी की आस्था पर चोट न पहुँचे इसलिए 15 अगस्त 1947 के दिन जिस भी धार्मिक स्थल की जो स्थिति थी, उसे यथास्थिति मानकर किसी भी विवाद से बचा जा सकता है। अन्यथा ऐतिहासिक सच स्वीकार करने के…

— Swami Prasad Maurya (@SwamiPMaurya) July 28, 2023

On Thursday (August 3), Allahabad High Court allowed the Archaeological Survey of India to proceed with a “scientific investigation/ survey/ excavation” of the mosque premises (except the ablutions area) ordered by a district court earlier to “find out…whether the [present structure] has been constructed over a pre-existing structure of a Hindu temple”.

There is a popular narrative about the religious tolerance of ancient India.

It is widely believed that the ancient Indian (Hindu) civilisation was peace-loving and tolerant, and that religious violence came to India with the Muslim invaders. Many Indians believe this intuitively, and most political parties have backed this narrative.

Jadunath Sarkar’s (1870-1958) influential five-volume History of Aurangzib, written between 1912 and 1924, says that Aurangzeb destroyed “many great shrines of Hindus”, including temples at Somnath, Mathura, and Varanasi. Sarkar juxtaposed this Islamic “intolerance and orthodoxy” with the tolerance and non-violence of ancient Indian Hindus.

Even historians who criticised Sarkar for being “overtly communal”, propagated some version of this claim themselves, emphasising India’s innate cosmopolitanism and religious tolerance.

In his Discovery of India (1946), Jawaharlal Nehru wrote: “There was…a freedom and flexibility of the mind and a tolerance of the spirit” among ancient Indians. “By their extreme tolerance of other beliefs and other ways than their own, they avoided the conflicts that have so often torn society asunder, and managed to maintain, as a rule, some kind of equilibrium,” he wrote.

But others have pointed to contradictions in this idea.

In her exhaustive study of Political Violence in Ancient India (2017), historian Upinder Singh argued that the narrative of the peace-loving Indian existed as part of a cultivated self-image which “affirmed the nonviolent ideology of Gandhian nationalism and projected a set of aspirations for India’s future” amidst its conflict-ridden present.

But this, Singh wrote, is based on “a very selective reading of Indian history”. “There is no doubt that the history of ancient India, as that of other parts of the world, was marked by considerable violence of various kinds.”

In his 2018 book Against the Grain: Notes on Identity, Intolerance and History, the late historian D N Jha wrote: “Demolition and desecration of rival religious establishments, and the appropriation of their idols, was not uncommon in India before the advent of Islam.”

There has long existed a link between religion and political authority.

In his ‘Temple Desecration and Indo-Muslim States’ (2000), historian Richard Eaton noted, “While it is true that contemporary Persian sources routinely condemned idolatry on religious grounds, it is also true that attacks on images patronised by enemy kings had been, from about the sixth century AD on, thoroughly integrated into Indian political behaviour.”

Eaton attributed this to the inextricable link between religion and political authority in pre-modern times. “With their lushly sculpted imagery vividly displaying the mutual interdependence of kings and gods and the commingling of divine and human kingship, royal temple complexes of the early mediaeval period were thoroughly political institutions … [and] the state-deity of the temple’s royal patron, express the shared sovereignty of king and deity,” he wrote.

Thus, “early Indian history abounds in instances of temple desecration that occurred amidst interdynastic conflicts.”

One of the examples Eaton presents is of the eleventh century Chola king Rajadhiraja I who, after defeating the Chalukyas, plundered their capital Kalyani, and took away a large black stone door guardian to his capital Thanjavur.

A second example Eaton cites is that of the Pallava Narasimhavarman I, who looted the image of Ganesa from the Chalukyan capital of Vatapi in 642 AD.

There is also enough evidence of the desecration of Buddhist sites.

Buddhism emerged in India around the fifth-sixth centuries BC during a period that scholars call “the second urbanisation of India”, a time of great socio-cultural change in the Gangetic plains. It emerged, along with other heterodox traditions such as Jainism, as a response to Vedic Hinduism’s highly rigid and ritualistic ways.

While today, the Buddha has been co-opted into the all-engulfing Hindu pantheon, the history between the two faiths has been marked by violence and persecution. Jha provided some details in ‘Brahmanical Intolerance in Early India’ (2016).

“The Mahabhashya of Patanjali states that Shramanas and Brahmanas are ‘eternal enemies’ (virodhah shashvatikah) like the snake and the mongoose, and the Buddhist monk Divyavadana (third century) describes Pushyamitra Shunga as a great persecutor of Buddhists,” Jha writes.

Pushyamitra (ruled c.185-c.149 BC) is said to have destroyed as many as 84,000 Buddhist stupas, demolished many Buddhist monasteries and learning centres, and wantonly slaughtered Buddhists. However, these accounts might be exaggerated, Romila Thapar points out in Asoka and the Decline of the Mauryas (1961).

Nevertheless, as Gail Omvedt in Buddhism in India: Challenging Brahmanism and Caste (2003) noted, while the specific numbers can be debated, the existence of great acrimony between the two faiths cannot be denied.

“Huan Tsang (or Xuanzang, the seventh century Chinese Buddhist monk who travelled extensively in India in the time of Harshavardhana) for example, gave many stories of violence, including the well-known story of the Shaivite king Shashanka, cutting down the Bodhi tree, breaking memorial stones and attempting to destroy other images.

“He also mentions a great monumental cave-temple construction in a mountainous area in Vidarbha, said to have been done by the Satavahana king under the instigation of Nagarjuna, that was totally destroyed,” Omvedt wrote.

Shashanka, the sixth-seventh century Shaivite king of Gaur (modern North Bengal), is said to have fought the Buddhist Harsha, and tried to destroy the original peepal tree under which The Buddha attained enlightenment.

More Explained

EXPRESS OPINION

May 13: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05