Caste is so integral to Indian society that even those who have converted from Hinduism to other religions follow caste. To compensate for the discrimination of caste, India has affirmative action or reservations in government jobs and educational institutions. This affirmative action is limited to 50% seats — the rest 50% are for “general” category, theoretically for everyone, in practice only for the upper castes.

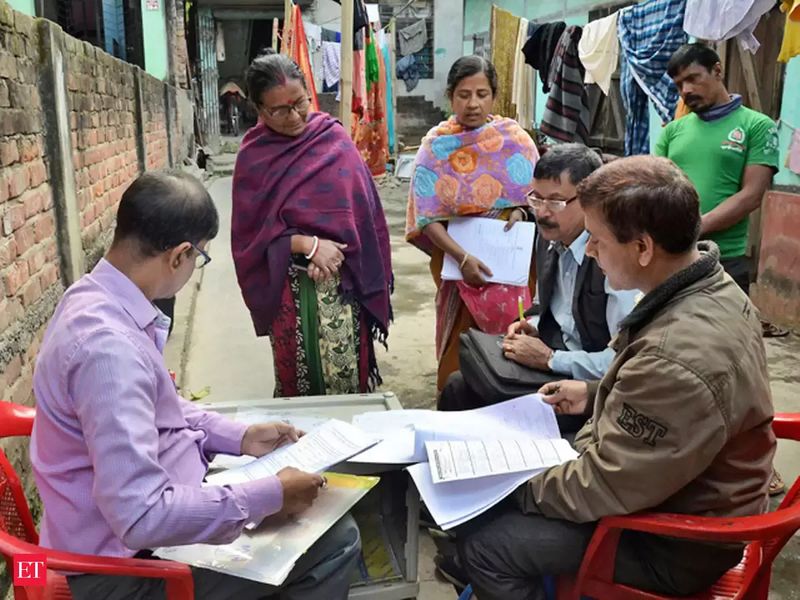

There has long been a demand for a “caste census”, for measuring how many people there are of each caste category, and how well they are doing. There was a national caste census in 1931, and another in 2011. But the one in 2011 was so badly done that proper final data could not be compiled — caste is so complex, it is a statistician’s nightmare.

The 2011 exercise was called the Socio-Economic Caste Census. Even if the final caste data could not be tabulated properly, the data has still been used extensively by central and state governments in targeting welfare schemes to the needy.

The main decadal Census was to be held in 2021 but we are in 2022 and it hasn’t even begun — the government says it has been put off due to the pandemic. Whenever the national census is held, among the issues to be resolved is counting caste.

India's ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) tries to be silent on the issue but everyone knows the BJP’s upper caste supporters are not in favour of a caste census. The number they are afraid of is the percentage of upper castes it will reveal, thus showing that India’s ruling elites are a small minority with a 50% reservation quota.

The demand for a caste census gained considerable ground in Bihar, the land of “Mandal”. A man named BP Mandal was a politician from Bihar who headed a commission that recommended broad reservations for the middle castes — known as the Other Backward Classes. The implementation of these reservations in 1990 changed Indian politics forever.

Hoping for a new polarisation

Among other things, the “Mandal” moment created space for OBC-led parties such as the Rashtriya Janata Dal and the Janata Dal (United) in Bihar, and the Samajwadi Party in Uttar Pradesh. Since the 2000s however, the OBC politics of “Mandal” has been withering away.

With the rise of Narendra Modi, the BJP has successfully co-opted most OBC communities. In this process, the BJP has made a deliberate choice to keep out dominant OBC communities such as Yadavs in UP and Bihar, Jats in Haryana, and Marathas in Maharashtra.

OBC politics has declined also because they have nothing new to demand — they got the reservations they wanted, even in the most prestigious medical and engineering colleges. There is no opposition to OBC reservations anymore. It has become accepted by Indian society despite rather loud opposition.

The OBC parties now see an opportunity in the caste census issue to bring about a fresh new polarising caste debate, leading to their revival. This hope has led to political parties in BP Mandal’s native Bihar to agree to have a “caste count” in the state. It is possible we may have a domino effect with other states seeing a caste count too, ultimately leading to pressure on the central government for a national caste count.

The OBC parties are being over-optimistic about this exercise leading to their revival. The 50% cap on reservations placed by the Supreme Court is an accepted norm today and it is unlikely to change. What could happen instead with nuanced data on caste is politics over “sub-categorisation”.

It is to be noted that the Bihar unit of the BJP has quietly backed the caste census, refusing to be on the wrong side of history like they were in 1990, when they opposed reservations for OBCs. If nobody opposes a caste census, it won’t be polarising. If it’s not polarising, it won’t be a counter to the politics of religion as it was in the ‘90s, when “Mandal” was pitted against “Mandir”.

Sub-quota for the small castes

Within the broad categories of General, OBC, SC (Scheduled Caste or Dalits) and ST (Scheduled Tribes), there are thousands of castes and sub-castes. Over the decades, some of them have risen through the economic ladder more than others, for a variety of reasons.

This has given way to demands for sub-categorisation. For example, Yadavs, Lodh and Kurmi in UP and Bihar are far more prosperous today than, say, OBC communities such as Sonar, Lohar, Nat, Darzi, Bind, Mallah, Nishad and so on.

Bihar has long had sub-categorisation and it was by fine-tuning the politics of sub-quotas that Nitish Kumar rose to power in the state. Recently, a few months before the 2019 general elections, the Narendra Modi government did a novel sub-categorisation, reserving some jobs within the general quota for the poor.

A caste count in Bihar or across India will bring up fresh data on the socio-economic levels of every caste community. The dominant OBC communities may find the tables turned on them, especially by the BJP. The politics of sub-categorisation may end up reducing how much benefit these dominant OBC communities are able to get from reservations, and increase reservations for the lower OBCs who today vote firmly for the BJP.

Caste census is an idea whose time has come. It can only be a good thing if we have good quality data on which communities are facing the greatest exclusion for educational, social and economic progress. It will help the poorest of the poor get more benefits from the state.

If the BJP has any anxieties about a caste census, it need not. The BJP could be its biggest beneficiary.