The Dongria Kondh, a tribe indigenous to orissa, have fought to protect the sanctity of mineral-rich Niyamgiri hills from a large corporation out to industrialise a land that they have held sacred for centuries. In 2010, the Dongria won a minor victory thanks to Government intervention. But the battl e may be far from over.

There are stories that we would like to tell backwards, fables about the weak conquering the strong, stories that have happy endings. Like in the movies, like in Avatar where the Na’vi tribe defend the Tree of Souls against invaders looking to exploit their land. In the real world, a similar battle is being fought in one of India’s eastern states, where the tribe of Dongria Kondh are fighting to protect the sacred Niyamgiri Hills from the mining giant Vedanta.

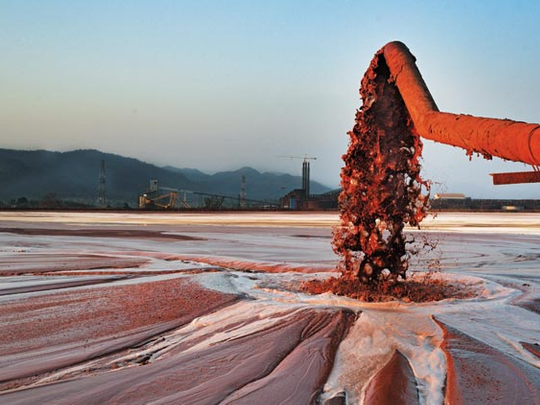

This story begins in 2003 when a British multinational company signed an agreement with the government of Orissa to mine the mountain and extract 70 million tonnes of bauxite. “The company told us that we would become rich, then came the bulldozers and demolished our houses,” says a native. The first step was to build the refinery in the village of Lanjigarh, which was razed to the ground and 103 families were evicted. After just a few years, the water sources disappeared and the land was poisoned by toxic waste. A swamp of red mud the size of four football fields

has become the symbol of this devastation. Here large pipes discharge water mixed with clay, waste and pollutants from bauxite processing. It didn’t take too long to contaminate the ground water, land and air. Around the swamp, bulldozers and earth diggers continue carving even more space to contain the ever-increasing waste.

But the people of the Dongria, fierce fighters, have opposed the mega-mining project with all their might. It’s a struggle reminiscent of David and Goliath. They had initially given up after protests and demonstrations resulted in a few deaths caused by clashes with the police. But the people refused to be intimidated. They were not ready to accept the destruction of their land and the bauxite-rich Niyamgiri hills. These are the hills where their ancestors lived and are still buried. This land is part of their history and culture, and they have always lived here.

They may not have official title deeds to this land, but this is their home. They took a pledge not to allow the mining company to take away the sanctity of their land. The Dongria Kondh is one of the most isolated tribes of the Indian mainland. An unofficial report estimates about 8,000 people live in the villages along the slopes of the Niyamgiri hills, a verdant land of forests, rich in a variety of flora and fauna. These people believe that they have the duty to defend this land and refer to themselves as jharnia (protectors of the streams). They protect their sacred mountain Niyam Dongar, which they believe is the seat of their God Niyam Raja, and the rivers that flow through its dense forest.

he Dongria people assembled at the top of this very mountain for a two-day meeting to pay homage to their land. A four-hour trek takes you to the top of this steep hill that has a green plateau. Here, around an altar that contains symbols of Christians, Hindus and Pagans, there is singing and dancing through the day and night. Small fires illuminate the expanse and the laughter of children fills the air.

“No, we cannot allow anyone to come here and destroy our land,” declares a man in the middle of the crowd during one of the many speeches. “They are ready to destroy in a short time what our people preserved and protected for centuries. But we will not allow it. We are ready to fight. Our land cannot be touched.”

The crowd remains silent. The darkness of night is about to fade away as a gentle breeze ushers in the pure light of an incredible dawn. Older women dance to the rhythm of the drums around the altar. Every now and then someone throws a handful of rice on the earth. Then, suddenly, there is silence. A prayer escapes the lips of one of the elders of the tribe as he cuts off the heads of two sacrificial goats. Blood flows and wets the soil. “This sacrifice is our gift to Mother Earth, another way to show our respect and love for her,” explains a young Dongria.

On the way back, a detour from the main path leads to a clearing on the side of the hill where you can get a good view of the land that these people are fighting for – green fields and small huts, the remains of the village of Lanjigarh. Next to the village looms the refinery and the red ponds of industrial waste. The refinery, enclosed by tall grey walls, is an odd sight in this landscape with its crane, pipes, sheds and hangars. Trucks carrying bauxite raise trails of dust.

“They are taking away our lives, they are stealing our souls,” says Prafulla Samantara, the 60-year-old leader of the National Alliance of People’s Movements. “They are putting our families, our traditions and our forests at risk. Our main goal is to protect our natural resources and to involve the entire community in this battle. Industrial development has a power of desecrating the environment and is a threat to our traditions and our way of life. Six tonnes of bauxite produces one tonne of aluminium, and poisons made by this transformation process contaminate the land and water with devastating effects on the environment and the ecosystem.”

In the summer of 2010, the Central Government in New Delhi asked Vedanta to suspend work in the mine and blocked the expansion of the aluminium refinery that had extended beyond at least six times the proportions of the original project. Though it had been difficult for the Dongria to stand in the way of an industrial giant like Vedanta, they had the support of the governments in London and Oslo and, surprisingly, the Church of England. They did so by withdrawing all their shares invested in the company.

In 2008, Amnesty International published the report Don’t Mine Us Out of Existence, which accused Vedanta of violating human rights, illegally occupying 26 hectares of land, and felling 120,000 trees. Several foundations and celebrities pitched in with support. In August 2010, the Indian government stepped in, and by October, Vedanta’s expansion projects were suspended, but the scars remain.

Bengopali is a small village of 300 inhabitants near the ‘border’ – the walls of the refinery. It is deserted, with empty streets and courtyards. I meet 90-year-old Kuli Maché, who tells me about the unemployment in the village. “Vedanta owns all the land around here, which they bought at a cheap price,” she says. “But at its refinery there is no place for the locals. Workers and labourers come from outside, particularly from Bangladesh who are content with low wages.”

In Chatrapur, the story is similar. “My father died in 2009, aged 45, because of a lung infection caused by the pollution,” says one of the villagers. “Everybody is dying here,” says Lodu Sikaka, a prominent leader of the Dongria Kondh. The refinery was a warning to the natives, and when news spread of the proposed construction of the mine in the hills, their rebellion was total. “Losing these hills is like losing our soul. We will prevent them even if they cut our throats and behead us,” he says.

The opposition to Vedanta’s push to mine the mountains has embroiled the company in a near decade-long dispute, and forced the Lanjigarh refinery to be run with bauxite from different mines across India.

A move that, according to company spokesman, has cost Vedanta half a billion dollars. In September this year, the company announced that it will shut down the refinery in Lanjigarh this December.

“We will be happy if the company leaves. If the refinery is there, they will keep trying to take our mountain, if not today, then tomorrow, or two years, or ten years from now,” says Sikaka. There are concerns that the company’s announcement is intended to pressure the government into allowing it to mine the Niyamgiri Hills. The matter was forwarded to the Supreme Court of India, but the case is not yet closed. For now, there is an uneasy calm around these hills.