The Naxalite insurgency, which was famously labelled as India’s “greatest internal security threat”, has gradually been weakening in stature since 2010. Through a combination of rural development programs and hard–line counterinsurgency tactics under the aegis of Operation Green Hunt, the geographical spread of Naxal–violence has been constrained to India’s central-eastern states. With India’s federal government optimistic about eradicating Naxalism, it leads us to question if Maoist ideology maintains influential in mobilising individuals towards violence. In this piece, we analyse the key dimensions of India’s counterinsurgency strategy and whether it can be held responsible for the decline of Naxalism.

For an in-depth, bespoke briefing on this or any other geopolitical topic, consider Encylopedia Geopolitica’s intelligence consulting services.

When the CPI (Marxist Leninist-People’s War) and Maoist Communist Centre merged to form the Communist Party of India Maoist (CPIM) in 2004, a coherent movement with a clear ideological core had emerged once again following decades of India’s Maoist political groups fracturing into splinter groups. Naxalism has pestered many of India’s states since its dramatic inception in the Naxalbari Uprising of 1967, but since then, has resulted in a tumultuous armed struggle. Recent trends have indicated that since 2010, major Naxal-related incidents have decreased at a steady rate, and have predominantly been confined to the Indian states of Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha and Maharashtra this year.

Fig 1.0 – Left-wing insurgency related fatalities in India

The Indian Government initially approached the Naxalite problem as a law-and-order problem, dealing with the violence through military measures. However, since the government shifted its emphasis towards a two-pronged approach incorporating nonviolent measures in 2006, the importance of development and police action has come into fruition. The combined initiatives of transforming underdeveloped regions through employment generation schemes, electrification of villages, education facilities, health centres and road connectivity have been at the forefront of the Indian Government’s plans in reducing localised conflict. Successive governments, including the current Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) administration, have continued to use development as a key counterinsurgency method to separate local populations from the Naxals. The Indian government identified 106 districts in nine states for rural development programs, notably including the flagship Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Programme. The adoption of rural development programs has had substantial impact on reducing violence in some regions, estimated to have reduce deaths by 61 percent, while in other regions, it has had virtually no effect on conflict reduction. The varied success rates of the development programs on reducing violence indicates that other root causes may be the principal drivers of persisting violence.

“The rise of Naxalism is a reflection of the need for development to reach the grassroots”

Coinciding with central government policies, state governments have also addressed the Naxal problem through development initiatives. For example, in Andhra Pradesh, the government has provided subsidised power to farmers, housing schemes, education scholarships and health insurance schemes in Naxal-affected regions. The Chhattisgarh government committed to provide financial compensation and employment to the families of those killed in Maoist violence. Furthermore, the insurance amount provided to the families of jawans killed in anti-Naxal campaigns was increased by the government of Jharkhand. While both central and state governments have carried out various schemes to tackle the development problem in Naxal-affected regions, state operations to eliminate Naxals in the past decade-and-a-half have been bloody to say the least.

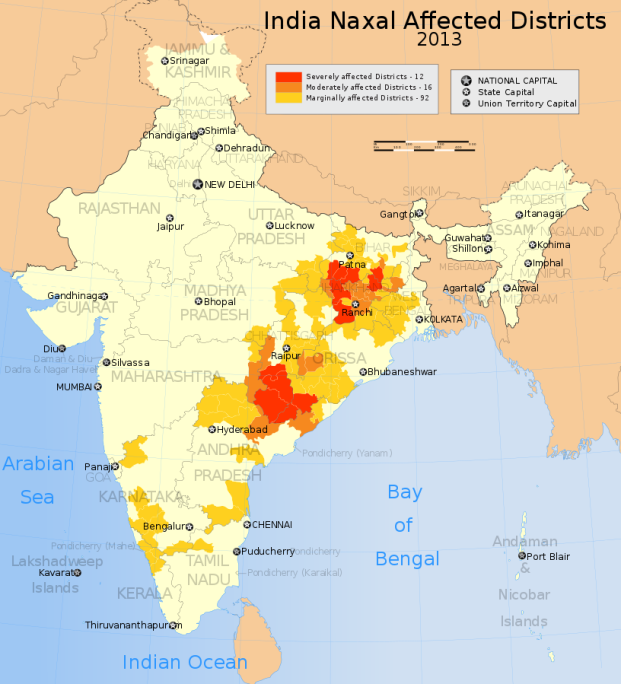

Fig 2.0 – Naxal-affected districts of India

Chhattisgarh’s secret funding and arming of the counterinsurgency militia group, the Salwa Judum, is an example of state government’s attempts (albeit desperate at the time) to fight the Naxals. When Chhattisgarh began its anti-Naxal operations, India’s Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) faced severe manpower shortages, requiring the recruitment of Special Police Officers (SPOs) from the community. SPOs, with their local knowledge of Naxal-affected areas, led raids on suspected rebel camps and were also tasked with the responsibility of legitimising the rising Salwa Judum movement. Despite initial fears of arming Salwa Judum members due to the potential of people defecting to the Naxal cause, many SPOs with connections to the Salwa Judum were provided with a firearm (either a .303 rifle or an AK47) following their training period. The Salwa Judum campaign, in conjunction with the SPOs, have played an influential role in attracting self-professed Maoists to switch sides and provide intelligence for local police forces. Many also hold double agent roles, acting as secret SPOs, to gather intelligence for future CRPF operations. While the informal counterinsurgency group has had some successes, the Salwa Judum have also been a conflict-escalator. Some have viewed ongoing Naxal/Salwa Judum clashes as an extension of historical tribal clashes and it is increasingly polarising and politicising Red vs. Saffron (Naxal vs. Hindu fundamentalist) tensions. The increasing tensions between Hindu nationalists and Naxals have led to attacks from both sides, creating fresh disputes in turn. Although, the efficacy and effectiveness of informal counterinsurgency groups are questionable, Naxal-affected states have been encouraged to form their own counterinsurgency forces similar to the Salwa Judum in the 2000s.

The reduction of Naxal insurgents has also been attributed to frequent instances of left-wing insurgents surrendering to local security forces. Surrenders have been common by many cadres and leaders of CPI-M, due to the attractive nature of a “surrender and rehabilitation” initiative. The policy’s objectives to wean away misguided youth and hardcore Naxalites and to ensure Naxalites who surrender do not find it attractive to rejoin the movement have been moderately successful, resulting in over 3,000 surrenders since 2016. While there is no clear-cut reason as to why Naxals surrender, various media reports have described cases of individuals becoming disillusioned with the ideology, but for many, it could simply be due to financial reasons. Many former-Naxalites have criticised the exploitative attitudes of higher elites who were live lavish lifestyles, while the cadres fight underground in remote forests. The “surrender and rehabilitation” of Naxalites is not a national policy, and as such has not resulted in success in all affected states, except from Madhya Pradesh. In Madhya Pradesh, the relentless crackdown on Naxals by the state police has resulted in a high number of surrenders, and if other affected states adopt a similar “surrender and rehabilitation” policy, coupled with intense security operations, then a similar trend of Naxal surrenders may become apparent.

Recent anti-Maoist operations in the Gadchiroli District of Maharashtra, and in the Balangir and Kandhamal Districts of Odisha, have represented the federal police force’s charismatic endeavour to suppress Naxalite activity across various regions of the country. India’s anti-Maoist “all-out offensive” is still ongoing nearly ten years later since its introduction in 2009, and although it has experienced varied success in different regions, the trends of Naxal violence has overall reduced since 2010. The relative strength of government forces, the high instances of surrenders and growing opposition to Maoists in local communities all indicate that the CPIM will struggle to maintain current operational levels.

Suggested books for in-depth reading on this topic:

Purchases made using the links in this article earn referrals for Encyclopedia Geopolitica. As an independent publication, our writers are volunteers from within the professional geopolitical intelligence community, and referrals like this support future articles.

- The Naxalite Movement in India (Prakash Singh)

- Contesting Marginality: Ethnicity, Insurgency and Subnationalism in North-East India (Sajal Nag)

- 13 Years: A Naxalites Prison Diary (Ramachandra Singh/Tr. Madhu Singh)

- India’s Naxalite Insurgency (Thomas F. Lynch III)

Encyclopedia Geopolitica readers can also benefit from a free trial of Kindle Unlimited, which offers unlimited reading from over 1 million ebooks and thousands of audiobooks.

Manish Gohil is a geopolitical writer specialising on South Asian Security and International Water Security. Manish holds extensive field-based research on Indo-Nepalese Transboundary Water Management and is currently conducting research on the participation of diaspora groups towards homeland secessionist movements.

For an in-depth, bespoke briefing on this or any other geopolitical topic, consider Encylopedia Geopolitica’s intelligence consulting services.

Photo credit: Cover image – Vishma thapa // Fatalities chart – South Asian Terrorism Portal // Naxal map – M Tracy Hunter

Amazing in-depth article.

I have been to these areas and personally, the greatest factors for the decline of the Naxal problem is economic growth. With the remote villages now connected to the main economy, the tribals know that if their children have a better prospect with education and hard work and not with militancy

Its an awesome article, We at Property Hunters shifted this service to a level much higher than the broker concept.

you can see more details like this article Properties For Sale in Qatar