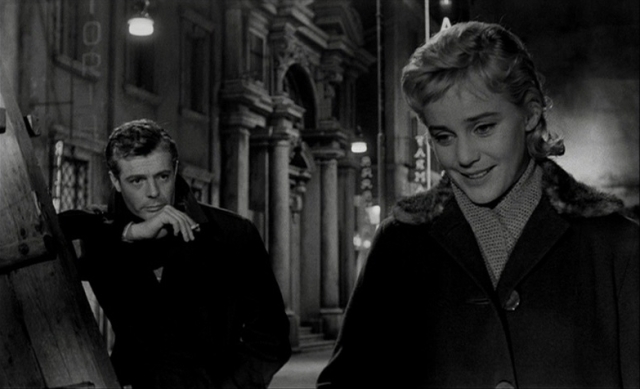

A city can be a wellspring of wondrous dreams or a desert of unbearable loneliness; for Mario (Marcello Mastroianni), the protagonist of Luchino Visconti’s 1957 film Le Notti Bianche, the city to which he’s just been transferred for his job is both — sometimes simultaneously.

As the film opens, Mario is returning from a day spent in the country with his supervisor and the man’s family. They might be mistaken for old friends, parting as they do with warm expressions of gratitude and talk of future excursions, but once Mario is left alone, a certain intrinsic solitariness in him starts to become apparent. (He eventually confesses that he “never said a word all day,” despite finding his companions to be nice people. “Boring, but nice people.”) Instead of going home to the hotel where he lives, he lingers on the street, wandering from place to place with no particular aim. While this may be preferable to spending the evening by himself in his room, he remains an isolated figure even in the midst of a crowd, and he’s still out roaming around close to midnight, when the city seems all but abandoned. He’s desperate for a little companionship — desperate enough to attempt a one-sided conversation with a stray dog, desperate enough to approach a young woman (Maria Schell) standing on a bridge in the belief that she’s a prostitute. She’s not, as he quickly discovers, nor is she contemplating suicide; her reason for being there is a positive one, at least in her own eyes.

This young woman — Natalia, by name — is another lonely soul. Her father left so long ago that she can’t remember him, and her mother ran off with another man, leaving Natalia to be raised by a nearly blind grandmother who keeps her pinned to her skirt (literally), lest she should behave in a similar fashion. They lead a reclusive existence, never leaving their house, where they repair rugs to earn a modest living. (When Mario first meets Natalia, he takes her for a foreigner, but she later notes that her grandmother is a foreigner, implying that she isn’t one herself; she’s simply spent all of her time confined with her grandmother rather than out in the world.) Small wonder, then, that the arrival of a handsome new lodger (Jean Marais) a year earlier made such an impression on the sheltered girl. A romance even appeared to be blossoming between them — until he abruptly terminated his lease. He was in serious trouble, he explained, and would have to go away for a year, and although Natalia begged him to let her come along, he refused to allow it. Denied this, she promised to await his return at the bridge, and she’s remained faithful ever since.

“I didn’t think there were girls like you left in the world. You might as well have told me you believe in fairy tales,” an incredulous Mario says after hearing her story. He assures her, speaking from a man’s perspective, that the lodger isn’t coming back, and suggests that she might be crazy (an idea that she finds highly amusing). Still, for all his professed cynicism, he proves as susceptible to unrealistic romantic dreams as she is. Over the course of the three evenings that he and Natalia spend in each other’s company — in fact, it doesn’t even take that long — he falls in love with her, convincing himself that if she just faces the truth about the lodger, he might have a chance.

Mario’s background is quite different from Natalia’s. “I don’t have a story,” he tells her, although it’s not because he’s been cut off from the world, as she has. On the contrary, his parents sent him away to boarding school when he was a child, and he’s moved around constantly ever since. “One year here, one year there — you meet a lot of people,” he says. “You meet, you separate, and then you start all over. I used to think that was the secret to a happy life. Perhaps I’m getting older, but I don’t like that anymore. I’d like to make some friends and keep them.” His wider range of experience hasn’t so much enriched his life as made him a perpetual outsider, much as her seclusion has done to her.

It’s only natural that both Mario and Natalia are overpowered by love when it comes to them, lonely as they are, but it does lead them to some troubling behavior. Mario, for example, tears up a letter that he’s promised to deliver to the lodger on Natalia’s behalf (as she’s heard that he’s back in town but can’t face him herself) and subsequently lies to her about it. She, meanwhile, once went into the lodger’s room while he was out in order to go through his belongings, “on the pretext of housekeeping.” In spite of her infatuation with him — or maybe because of it — she doesn’t seem to know him very well at all. When she and Mario are composing her letter to the lodger, she instructs him to start out with “Dear sir,” then changes it to the scarcely less formal “Kind sir.” She also seems undisturbed by hints that he may not be the type of man with whom she ought to become involved: his year-long absence due to unexplained trouble, above all, and perhaps the fact that all of the books he lends her are about “stranglers, policemen, international spies.” This might be the result of her naivete, but it could be a sort of willful obliviousness, a need to block out unpleasant truths for the sake of happiness — like her belief that the lodger will return to her, like Mario’s hope that she’ll fall in love with him instead.

“So you’re a dreamer too,” Natalia says with a smile when Mario tells her how he likes to walk around the city, alone with his thoughts. “Well, you know how it is,” he replies. “The imagination boils over, like water in a coffee pot. But it’s a mistake, because you end up believing there’s something real and tangible in your dreams, and you neglect life and reality. This reality right here!” At the time, they’re in a nightclub packed with youthful dancers, a happy scene and, for Natalia, a totally new experience. However, reality can also be a harsh and even sordid thing. There are plenty of men, women and children out enjoying themselves, to be sure, but as the evenings wear on, Mario and Natalia find themselves surrounded primarily by prostitutes, thugs and innumerable homeless people huddled around fires or sleeping on the ground. Aesthetically, too, the city can be less than appealing, with its crumbling walls and piles of trash and mud-splattered buses. Sometimes fantasy, dreams, hope — self-delusion, even — are the only things that make life bearable, though the fallout when reality breaks in might be all the more painful.

“God bless you for the moment of happiness you gave me,” Mario tells Natalia. “Even a moment’s worth can last a lifetime.” A fleeting, ethereal moment of happiness in which, for once, fantasy and reality cross paths, like two strangers in the night.

This post is part of The Free for All Classic Film Blogathon, hosted by CineMaven’s Essays from the Couch. Click the banner above to see all of the other great posts.

Pingback: THE FREE FOR ALL BLOGATHON | CineMaven's ESSAYS from the COUCH

Thank you for joining my blogathon with this lovely essay on this gossamer of a film. It’s a new favorite of mine and your writing is so elegant about it. Thanks again !

~ Theresa

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, and thanks for hosting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This sounds like a very moody piece, and not something I could have appreciated in my youth. I’m glad I am being nudged in its direction today.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hope you enjoy it!

LikeLike

Sounds like a beautiful and heart-breaking film. I would imagine a person should keep the tissues handy…?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, that might be a good idea — certainly at the end, if not earlier on.

LikeLiked by 1 person