RAGHU RAI

MUKUL KESAVAN

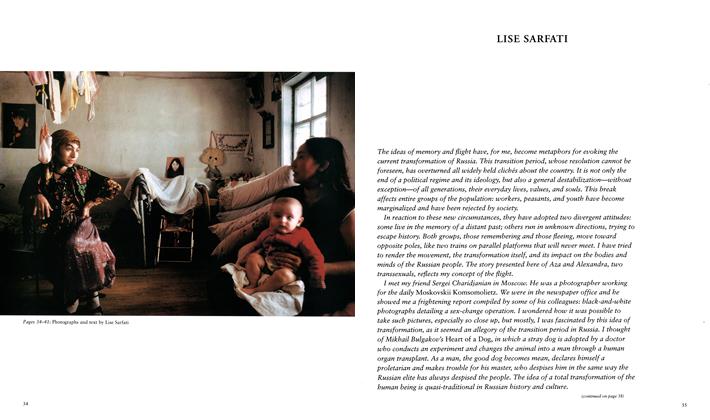

I was five years old when the country was partitioned, says Raghu Rai. That makes him about fifty-five, because it's nearly half a cen tury since that happened, that and Independence. Fifty years of freedom, with the evil frisson of genocide thrown in-it's a nat ural for the color pages, and every editor in India wants a piece of this anniversary.

Raghu Rai can remember running across roofs in 1947, flying from a mob with murder on its mind, because the small town in west Punjab that his family lived in had abruptly become part of another country. He thinks they fled to Amritsar, though he isn’t sure, but he can clearly remember times when there wasn’t enough

Life through a lens has been his textbook and he has been educated by his camera, click by click. Rai is instinctively populist in his view of photography. Unlike Strand or Cartier-Bresson he doesn’t see the world as his subject; India is big enough for him.

to eat. It was a large family, ten siblings in all, and one of them, an elder brother, a photojournalist in his own right, taught him how to use a camera. Success came early; a year after starting as a news photographer, he became chief photographer of the best daily newspaper in the country at that time, the Statesman.

Today, Rai is a star, but before that, he is the made-good son of migrant parents, one of a million Punjabi refugees, legendary for their resilience in adversity, for their ability to build new careers out of the rubble of their post-Partition lives, and he shares with them their pride in being self-made men.

I don’t read, he says more than once in the course of the conversation. He isn’t confessing to illiteracy; it is his way of saying that he isn’t bookish, that he doesn’t depend on other people for his ideas. Life through a lens has been his textbook and he has been educated by his camera, click by click. Rai is instinctively populist in his view of photography. Unlike Strand or Cartier-Bresson he doesn’t see the world as his subject; India is big enough for him. You need to know a place, a country, before you can photograph it as an insider, he says. Without that hard-won intimacy, photography becomes spectacle; thus Cartier-Bresson’s Indian pictures are, for Rai, brilliant but indefinably foreign. He tried to illustrate this with an analogy from the cinema. David Lean’s Passage to India doesn’t work for Rai because Lean knows so little about the country that, besides getting social detail all wrong, India’s landscape doesn’t show through as panoramically as it should have done in a Lean epic. So far, Rai’s instinct is true: Lean’s film is almost comically inept. But then he cites Dr. Zhivago as a successful example of Lean’s work, where the grandeur of Russia’s landscape is authentically used as a backdrop for the story. The problem with this is that (a) Lean knew about as much about Pasternak’s Soviet Union as he did about Forster’s Raj and (b) Dr. Zhivago wasn’t shot in Russia. The analogy tells us more about Rai than it does about Cartier-Bresson: like many autodidacts, Rai isn’t good at theorizing his prejudices. Not reading has its down side.

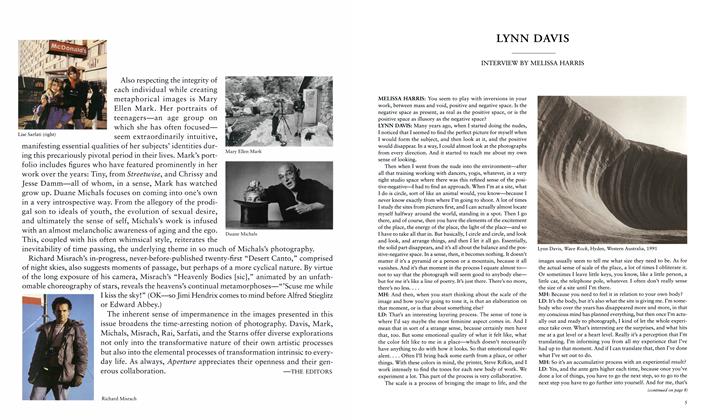

Rai’s credo is the photographic equivalent of social realism. A photographer’s job, he says, is to cut a frame-sized slice out of the world around him, so faithfully and honestly that if he were to put it back again, life and the world would begin moving again without a blip or stutter. According to him, an older generation of Indian photographers became trapped in a sterile pictorialism, and he constantly counsels younger photographers to beware the pernicious influence of painterly ideas, ideas that encourage the making of structured, harmonized, centered images. The romance of painting has to be resisted because it retards the development of an independent aesthetic for photography. According to Rai, contemporary photography values the anarchic frame, with the action bleeding off into the edges, not tunneled into the center. For him, the evolution of photography is linear, with pictorialist mastodons ceding ground to realist primates.

Rai’s credo is the photographic equivalent of social realism. A photographer’s job, he says, is to cut a frame-sized slice out of the world around him, so faithfully and honestly that if he were to put it back again, life and the world would begin moving again without a blip or stutter.

He disowns much of his own output—his book on the Taj Mahal, for example—as pretty work that pandered to a tourist vision of India. Around the time he turned fifty, he undertook a reappraisal of his work. He stopped working as a photo editor for India Today, the country’s leading news magazine, and concentrated on creating a personal, expressive body of work, free of the constraints of photojournalism.

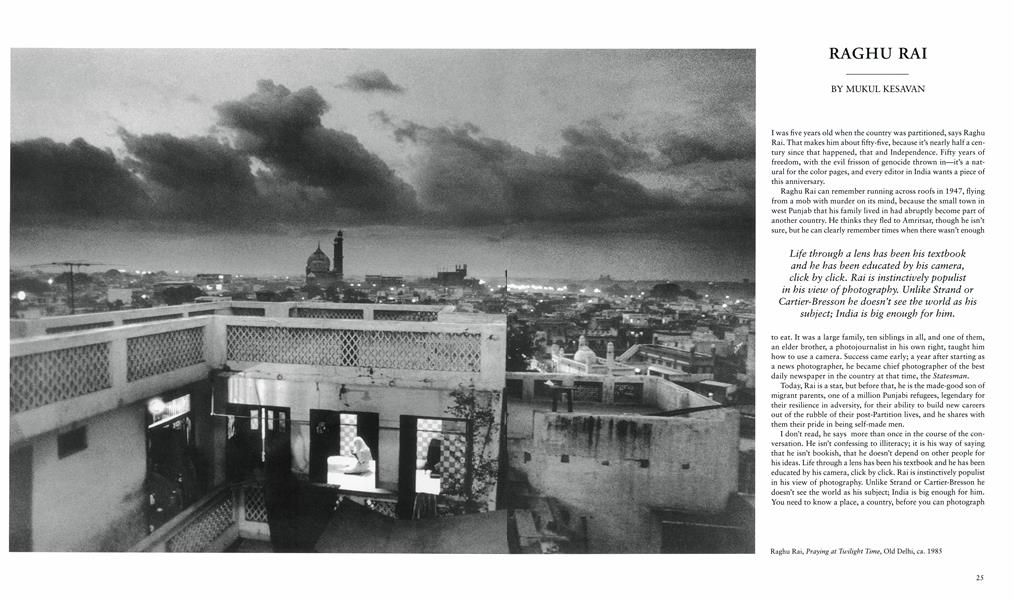

In 1994, he produced a new book of photographs of Delhi, mainly in color. He thinks its pictures are more interesting and mark a new direction; after years of focusing on a single event and dramatizing it, he’s now working more complexity into every inch of the frame, even its margins. Also his new pictures have less accessible subjects: he’s made a self-conscious attempt to avoid Indian exotica—cows on main streets and other suchlike quaintnesses. People want you to become an entertainer, he says, and he finds some of his work too predictably Indian. The trouble is, he says in a plaintive aside, that much of India is like that.

He finished a book of pictures centered on Mother Teresa, and he is near the end of another book on Indian classical musicians, a project he has been working on for years. He’s about to mount a retrospective of his work at the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi for which he’s spent nearly two months in the dark-

(continued on page 31)

(continued from page 26)

room, and there’s no end in sight. He’s his own curator; not because he wants to be—he would love to sit down with a discriminating critic and choose images representative of his oeuvre—but simply because there is no curatorial tradition in India. What he misses most working in India is not the big agencies or the big magazines, but informed critics, curators, and peers to bounce ideas off. He reckons he’s lost years of growth as a photographer because of the absence of an institutionalized culture of photography, of committed contemporaries. He acknowledges few Indian precursors or peers; Sunil Janah, best known for his harrowing pictures of the Bengal famine, is almost the only photographer mentioned. Too many of the others are journeymen, unwilling, in his picturesque phrase, to smoulder in the fires of creativity. He tried to create a forum for Indian photographers, but the factionalism and self-promotion and argument that attended its birth made him withdraw.

Most of the pictures in his retrospective will be in black-andwhite, though there will be a section of color photographs. His signature work was done in the eighties in black-and-white for India Today—vertigo-inducing images made with a wide-angle lens, where foreshortened figures from newspaper headlines dominated the center and/or keeled away toward the edges. Since then, he has divided his time between black-and-white and color, but his partiality to the former is obvious. Color, he says, is good if you’re working without a specified subject. But it’s limiting, because it constrains the circumstance in which you can shoot. It’s hard to control, and if you’re shooting a story you can’t stop life to accommodate the demands of the perfect color exposure. Black-andwhite is much better for that; it lets you concentrate on the subject. He pauses. Black-and-white gives you a filter that unifies the sky.